The Big Question: How much do prisoners earn, and why was their pay rise blocked?

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Why are we asking this now?

Prisoners were due from today to receive their first pay increase for more than decade. That was until Gordon Brown learned of the planned 37.5 per cent rise and vetoed it on the spot.

The amounts of cash involved in the mooted boost in their minimum pay, from £4 to £5.50 a week, are minuscule. But the Prime Minister – sensitive to the political storm over the abolition of the 10p tax rate and anger among public sector workers over their below-inflation pay deals – believed such an increase would send out the wrong message at a time of national belt-tightening.

His "penny-pinching" intervention, however, has provoked fury among penal reformers, who claim it will be counter-productive by deterring inmates from getting the education, skills and work experience that will prepare them for their return to the outside world.

How can prisoners earn money?

Cash, in the form of notes and coins, is banned in the 139 jails in England and Wales for security reasons. Offenders instead earn credits towards an account which they can then use to buy items such as food, toiletries and cigarettes, from the prison canteen.

The prison service offers work to about 24,000 inmates at any one time, just under one-third of the prison population. About 10,000 are employed in workshops producing clothes, woodwork, metalwork and printed items. Four thousand of them work for external contractors in such tasks as laundry and manufacturing headphone ear-pieces for airlines.

About 25,000 attend educational courses, from programmes designed to address offending behaviour and improve literacy to obtaining vocational and academic qualifications.

How much can prisoners earn?

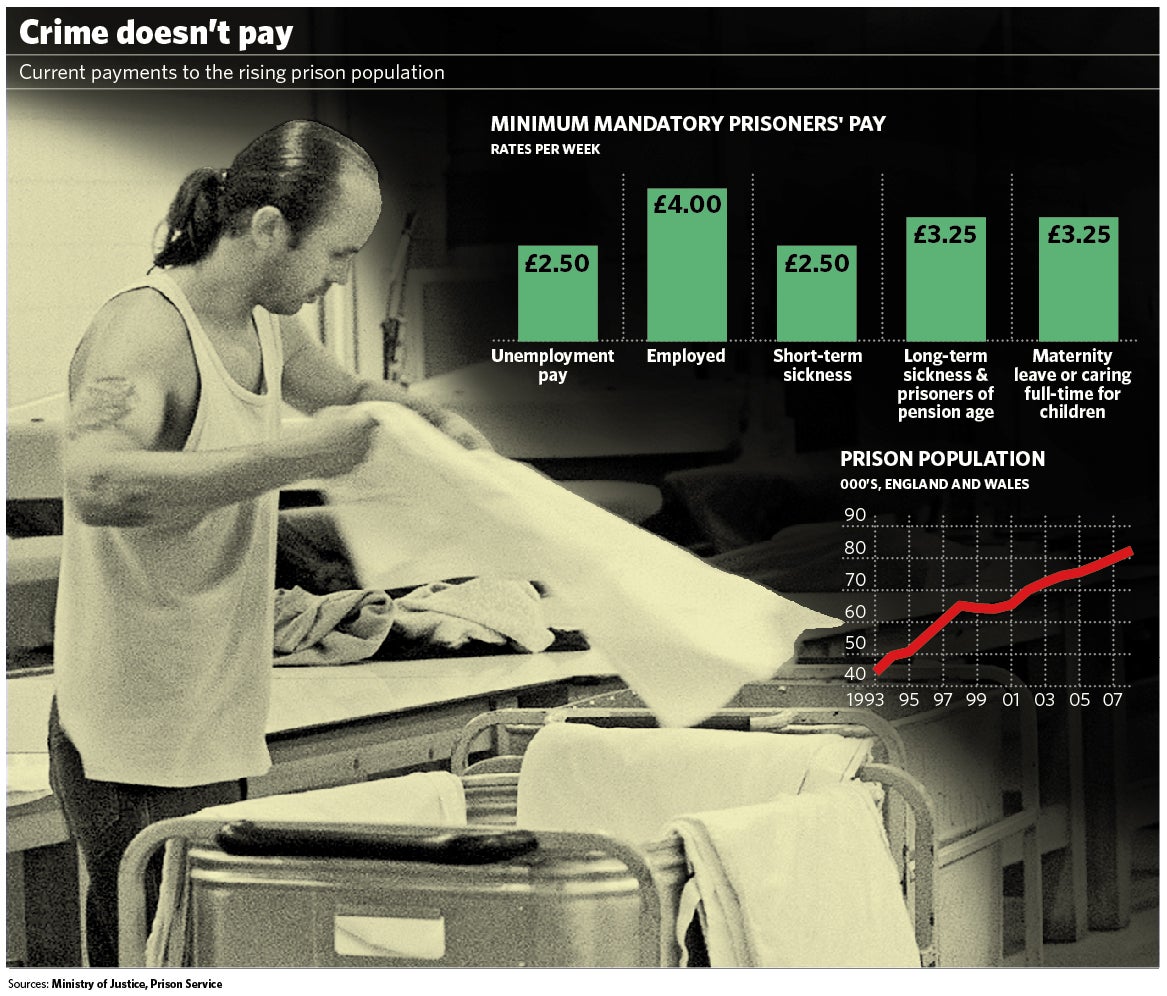

Minimum rates of pay are laid down by the Prison Service, although the actual rates vary according to individual jails and the kind of job they are doing or the course they are taking. Although the minimum rate is £4, the average weekly pay is £9.60.

Other benefits mirror those in the outside world even if the rates are vastly lower. Prisoners are entitled to unemployment pay of £2.50 a week if they want to work but nothing suitable is offered to them. They can claim £2.50 for short-term sickness or £3.25 for long-term sickness or if they are above retirement age.

Their accounts are "held" by the prison and can receive small top-ups from families and friends if they have earned the privilege.

What can prisoners spend theirmoney on?

There's a range of items on sale in prison shops, most of which are supplied by the American conglomerate Aramark. Examples of its prices include £1 for a packet of chocolate digestive biscuits, £2.83 for 12.5g of Golden Virginia tobacco, and £2.23 for a 250g tube of shower gel. For many, the bulk of their "earnings" go on BT phonecards, while others use the money to rent a television. The amount they are allowed to spend depends on their level of privileges. Prisoners on the basic regime are only entitled to £3.50 of spending per week, rising to £14 to those on the standard level and £23 for those on the enhanced level. They can move up the scale in return for good behaviour.

Why were the rates of prisoner payabout to go up?

Although its budget is being squeezed, the prison service decided that it had no alternative but to raise the rates; they had been frozen since 1992, and clearly an increase was long overdue. The proposals would have meant raising minimum weekly pay from £4 to £5.50, unemployment and short-term sickness pay from £2.50 to £4, an increase of 60 per cent, and long-term sickness pay would have gone up from £3.25 to £4.75.

Why did Gordon Brownobject so strongly?

The Prison Service Management Board agreed details of the proposed increase on Monday. It appeared not to have told the Ministry of Justice that the rises were about to be implemented, possibly on the basis that it was an entirely operational matter. Downing Street disagreed when it discovered the proposal and, in further evidence of his propensity for micro-management, Mr Brown personally vetoed it within 24 hours, explaining: "We are now debating a contract with prisoners so they are better behaved... I think any debate about what prisoners receive in pay should be part of that new contract."

The reality is that the Government did not want to have to deal with the damaging headlines that would probably have followed on the eve of today's local elections.

So is life behind bars cushy?

It is, according to Glyn Travis, the assistant general secretary of the Prison Officers' Association, who told last week of prostitutes and drugs being smuggled into jails and of inmates even passing up chances to escape because they were enjoying themselves so much. Penal reformers and prison inspectors paint a very different picture of a system stretched to breaking-point, with a record 82,000 offenders crammed into jails.

They warn of more criminals being forced to "double up" in cells designed for one and having less time to exercise because of financial cut-backs. Rising tensions have led to increasing suicide levels and even the threat of riots, they say.

Why should prisoners get a rise?

Juliet Lyon, the director of the Prison Reform Trust, said the "penny-pinching" move betrayed a lack of understanding over the part that prison can play in cutting crime. She said: "The Prime Minister has reduced the opportunity for people to buy a phone card to call home, sort out housing or try to get work." Paul Cavadino, chief executive of the crime reduction charity Nacro, said: "If we want to cut reoffending we should be moving towards better work opportunities for prisoners with more realistic wages."

What happens next?

The issue of pay is being examined by David Hanson, the Prisons Minister, as part of an effort to draw up a new "compact" between jails and their inmates. It is likely to result in a new scale of payments and spending entitlements, linked to their behaviour and ability to stay off drugs. The Government is, meanwhile, promising to expand the range of work opportunities offered to offenders. If they finally win their decade-old pay rise, though, it is certain to be announced at a time of minimum political damage to the Government.

Should prisoners have a pay increase?

Yes...

* Although they are offenders, they have not forfeited the right to be treated fairly.

* Phone cards are essential for maintaining an inmate's link with the outside world.

* By encouraging prison inmates to work, society benefits because they pick up skills that will rehabilitate them.

No...

* They have been convicted of a serious offence and are lucky to get any money.

* No increase can be justified when law-abiding citizens are getting a below-inflation rise.

* The cash saved could be better used for improving facilities and accommodation in jails.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments