The Big Question: Has the divide between Britain's social classes really narrowed?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

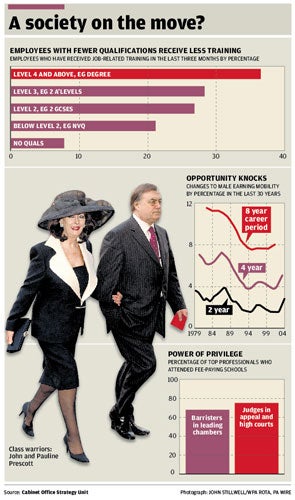

The Government published a document yesterday which made the startling claim that, after a long period of social stagnation, British society has become socially mobile again. For 30 years, according to Getting On, Getting Ahead, the paper prepared by the Cabinet Office's strategy unit, there was no appreciable movement between social classes, although society as a whole became better off. Children born in relative poverty left school with fewer qualifications than children from more comfortable homes, and went into low-paid work. But since 2000, the Government claims, that general pattern has changed for the better.

On what does the Government base this claim?

It is well known that a child's chances of achieving the benchmark of five good GCSEs, including maths and English, are heavily influenced by social background. Children brought up in low-income households are much less likely to succeed than the children of successful, financially secure parents. But studies that compares GCSE results achieved by children born in 1970 and children born in 1990 show the gap has closed to a "statistically significant" degree. The Cabinet Office minister, Liam Byrne, attributes this to the attention that the Labour Government has paid to pre-school education and post-16 vocational training. Another factor may be the millions the Government has invested in school buildings.

Is that it?

There is more. What the Government calls "earnings mobility" has risen since 2000. There was movement up and down in the 1960s and 1970s, but less in the 1980s and 1990s, when people generally stayed on whichever rung of the income scale they were born to. Since 2000, movement has resumed – though not at the top. People born into the wealthiest 10 per cent have stayed there.

Does this mean that more children born in council estates are moving into well-paid jobs?

It is too early to judge what the social impact of these findings will be because children born in 1990 are still teenagers. There is a recession ahead, so who can tell what jobs will be available for them in a few years? Abigail McKnight, co-author of one of the reports on which the Cabinet Office paper is based, warned: "How this is going to play out, we don't know. Obviously, you need a very long run of data, so we will see what the recession brings."

But surely the gap between rich and poor has been getting wider?

True. The very rich just go on getting richer. In July, the Institute for Fiscal Studies produced a paper which suggested that the disparity between incomes is at the second-highest level it has been since accurate records began in 1961. However, that is a separate issue. New Labour has never claimed that it was going to stop people from becoming very rich. What it did promise was that it would remove the obstacles which prevent people at the bottom of the ladder from climbing any higher. Yesterday's report is their evidence that the Government have made a start.

How is class defined?

This used to be a simple question to answer. When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were examining the British class system in the middle of the 19th century, there were three classes. The aristocracy, or upper-class, owned the land and factories, and were so well off that their children did not need to work for a living. The bourgeoisie, or middle class, worked in offices and were paid salaries. The proletariat owned almost nothing and worked with their hands in return for wages, if they could find work.

However, as Bernard Shaw wittily pointed out in his play Pygmalion, a person's class could be immediately deduced from the way they spoke. A dropped "h" or a shortened vowel sounds were sure signs of a lower-class background. Even when the flower girl in Shaw's play, Eliza Doolittle, has learnt to pronounce words with an upper-class accent and to dress, stand and sit like a lady, she gives herself away by exclaiming "not bloody likely" – albeit in a cut-glass accent. Shaw's audiences would have appreciated how shocking this was, because culture, sport and entertainment were socially apportioned too. The middle and upper-classes went to the theatre, while people like the Doolittles went to the music hall.

Has the old class system changed?

Britain's class structure loosened after the Second World War. The landed aristocracy became relatively poorer, the number of people in manual work decreased, and the 1944 Education Act opened universities to more children whose parents could not afford private education. Television knocked down some of the cultural barriers between classes. In the 1960s, there was the famous Frost Report sketch featuring John Cleese in a bowler hat, Ronnie Barker in a cheap suit and Ronnie Corbett in a cloth cap, satirising the way people dressed and spoke according to how they perceived their social status.

But even as that sketch was broadcast, the social stigma attached to speaking with a working-class or regional accent was breaking down. Middle-class teenagers were swept up in Beatlemania just as much as their working-class contemporaries, and in 1965 a former grammar school boy, Edward Heath, succeeded the former 14th Earl of Home as leader of the Conservative Party.

Now, even if the Tory leader is an old Etonian, he likes to be known as "Dave" and to be seen not wearing a tie. This fad for the trappings of downward mobility was brilliantly captured in a 1984 TV advertisement for Heineken, featuring a School of Street Credibility where a tutor is struggling to teach an upper-class girl – Eliza Doolittle in reverse – to drop the "t" from "water" and to sound the "j" in "Majorca".

So is class finally disappearing?

No, the class system may be better concealed than it used to be, but it is alive and well. It persists in the mind, as anyone who watched the recent BBC2 series, Prescott: The Class System And Me, will have seen. John Prescott rose to the second-highest political office in the land and yet, as he freely admits, he never shed the sense of inferiority that came from being an 11-plus failure and a ship's waiter. When the Earl of Onslow congratulated him on his success, adding: "You shouldn't have a chip on your shoulder, dear boy!", Mr Prescott's immediate riposte was, "Where did you go to school?"

Where people went to school is still a very powerful indicator of their chances of success, despite the slight closing of the social gap trumpeted by the Government yesterday. A month ago, the shadow Schools Minister Michael Gove released a geographical analysis of last year's GCSE examination results to demonstrate just how wide it is. In the predominantly white, working-class area of Holme Wood in south Bradford, only 3.3 per cent of teenagers achieved five good GCSEs. In nearby Ilkley, the figure was 86.3 per cent. In the London borough of Richmond, it was 100 per cent. The class system is more than a chip on Mr Prescott's shoulder; it is there, in the classroom still.

Is the United Kingdom becoming a more equal society?

Yes

*The "bog standard" comprehensive schools that condemned children to low achievement are disappearing.

*An 18 year old from a sink estate is likely to be better qualified than a 38 year old from the same background.

*Those privileged by birth, like the Conservative leader David Cameron, try not to flaunt their advantages.

No

*The gap between the rich and the poor in Britain has almost reached a record level.

*The worse off a family is, the more likely it is to be adversely affected by the looming recession.

*A comfortable background is still the most reliable passport to a good education, even if the gap is narrowing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments