The bald truth: How author Nick Coleman's thinning hair made him heir to a thousand sorrows – and a Wayne Rooney sympathiser

'You do learn to live with it, in due course, even as a young man, as we all must learn to live with not only who we are but how we are perceived'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I saw my death for the first time in the winter of 1979. I saw it rising like the moon through a forest at night. I was 19.

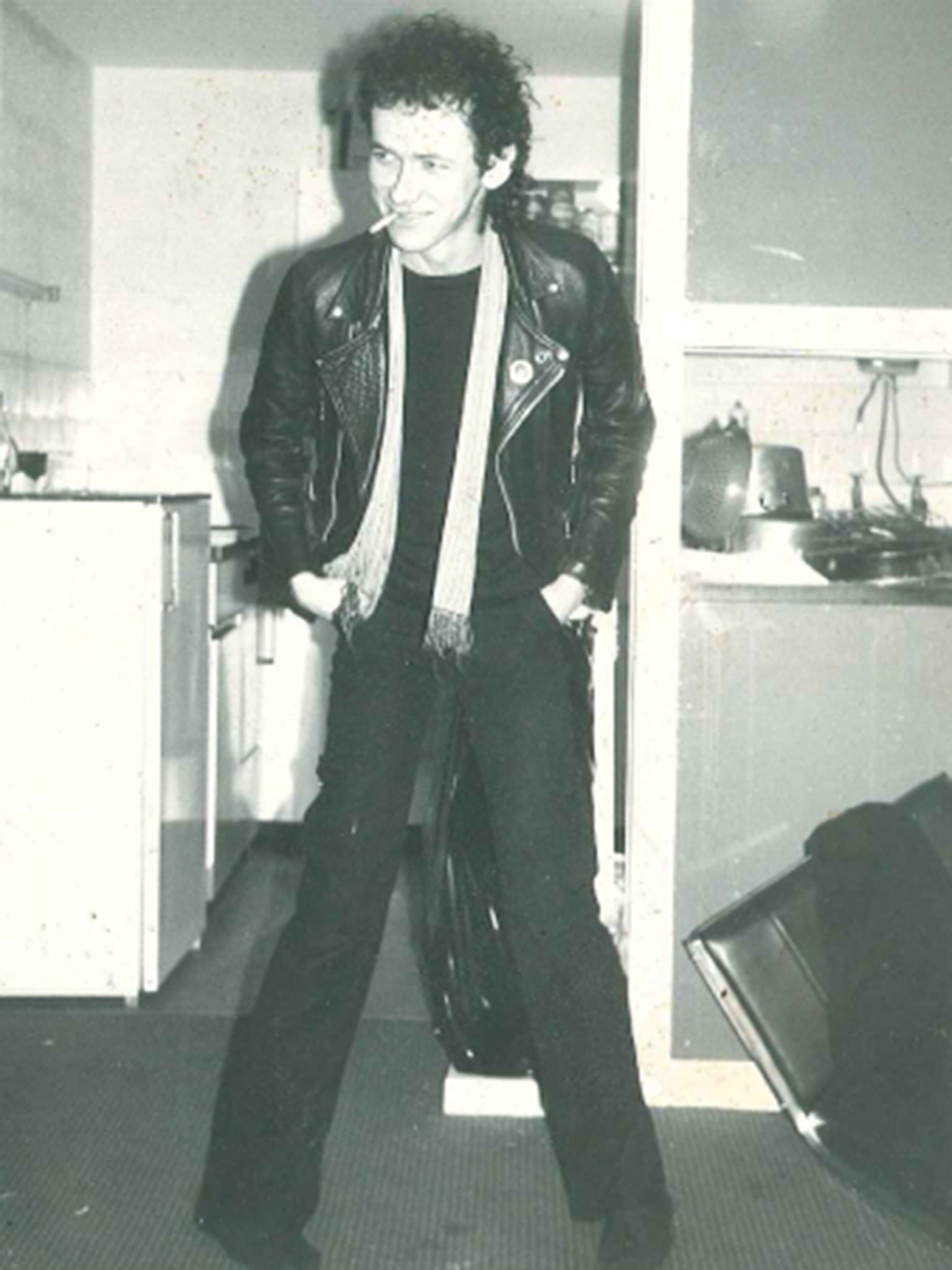

There was a mirror on the wall of my student digs, between the wardrobe and the window. I stood at that mirror every morning to tease my mop of curly 19-year-old hair into what I regarded as a punk-acceptable version of a Keith Richards stook: as tall as possible at the top, as pendulous as possible behind the ears – not easy when your hair is essentially a bush.

I was not in the habit of spending ages over it – that would have been narcissistic – but I did make sure that the arrangement on my head looked as right as possible every morning. After all, one had to be rockin’ for the first lecture of the day, and I was always late. So a quick glance and a perfunctory poke with splayed fingers were my morning ritual.

And then one cold morning I poked and recoiled. What the fuh…!?! I must have blinked too, to get the sleeping rheum out of my eyes – something had got into them, surely… Because this could not be right. No way. It must be some sort of illusion, a trick of the light; a continuation of last night’s frightened dream, perhaps? For there, clearly visible in the mirror, rising like the moon among thinning dark clouds, was a white hemisphere both beyond my hair and yet somehow also in amongst it, a hemisphere picked out with appalling clarity by cold Mancunian morning light. Luminous, radiant, pale. Lunar. A bald head hardly veiled at all by curls.

My scalp.

My skull.

My death.

I did not draw breath for many long seconds. I almost certainly took not a single note at that morning’s lecture.

I was recently reminded of that frozen moment in far-off 1979 when Wayne Rooney appeared in front of the cameras to do his statutory media duty, following an England match earlier this summer. He stood there, squarely in front of a post-match patchwork of brand signage, next to Jack Wilshere, looking every inch the slightly older statesman of English football, helped in his dignity no doubt by the earnestness of his younger companion and by the deferential tone of his interviewer.

“Wayne,” the guy with the microphone was saying to him. “You must be pleased with blah de blah de blah de blah… And young Jack here – as his captain, you must feel proud of his display de blah de blah de blah…”

Nothing came back. Rooney’s marble eyes expressed only their blueness. Cerulean zilch. You could see that even if the interviewer’s words were getting through to Wayne, then they were secondary in his mind to a much graver concern. His mind was elsewhere, his thoughts fugitive. And his hand… it kept straying up past his face for a moment and then back down again, anchoring itself to his cheek, just in front of his ear. Scritch-scratch. Then down. And then up again, this time to alight on his chin, where it enjoyed a more extensive scratch. And then a third time, the Rooney nostrils benefiting from the squeeze and tug of thumb and forefinger. It just wouldn’t stay down, that hand. Up it would go, as if heading for the summit of Wayne… and then divert en route for a fiddle on the lower slopes. Up, divert, fiddle. Up, divert, scratch. “Yeah, yeah,” concluded the Roon at the end of the interview, with obvious relief. “Thanks.” And the camera cut away just as his hand was making its northerly journey for the seventh or eighth time.

I thought: poor guy. And then I thought: but he’s Wayne Rooney. He is as wealthy as Croesus, rich in acclamation, abundant in computer games, lacking only in hardship. He is the England football captain. After his playing career finishes, he will never have to labour again. His life is probably as close as it can ever get to how he’d like it to be.

And then the thought came again, more insistently this time: poor guy. I just couldn’t help it. Because I recognised that hand. I recognised its strange, stray, distracted movements and the suggestion that went with those movements of a certain distraction of mind. There was something about the compulsiveness of that gesture that I knew. In particular, I understood by instinct what lay behind the sudden changes of direction that affected Rooney’s paw as it made its uncertain journey around the moon of his head. I recognised it all from my own passage from youth into adulthood, when I was 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and losing my hair in handfuls.

Thankfully, back then, I did not have to face television cameras and the scrutiny of supermarket magazines; the only people I had to look in the eye were friends, family and customers. But even then, when fully confident of the goodwill of a companion, I still did it. I too was unable to resist the temptation to put my hand up to my head to cover it up or to straighten things out, to scratch an itch or to confirm that what little hair I had left was still there, where I left it a few minutes ago. You know: to just check in. When feeling exposed or vulnerable I performed this nervous routine with one or other of my hands more or less continuously.

Most vividly of all, I recall the exercise of will required to divert the orbiting hand away from the scalp – because the last thing you want to do is draw attention to the fact that you are losing your stook. And so, half-way through the gesture, you’d divert the hand to Frankfurt, to make it look as if you’ve just been visited by an itch in some German town.

That’s one of the things that happens when you’re going bald prematurely. Your scalp itches all the time. It drives you mad, partly because the itch is unscratchable and partly because it keeps moving around.

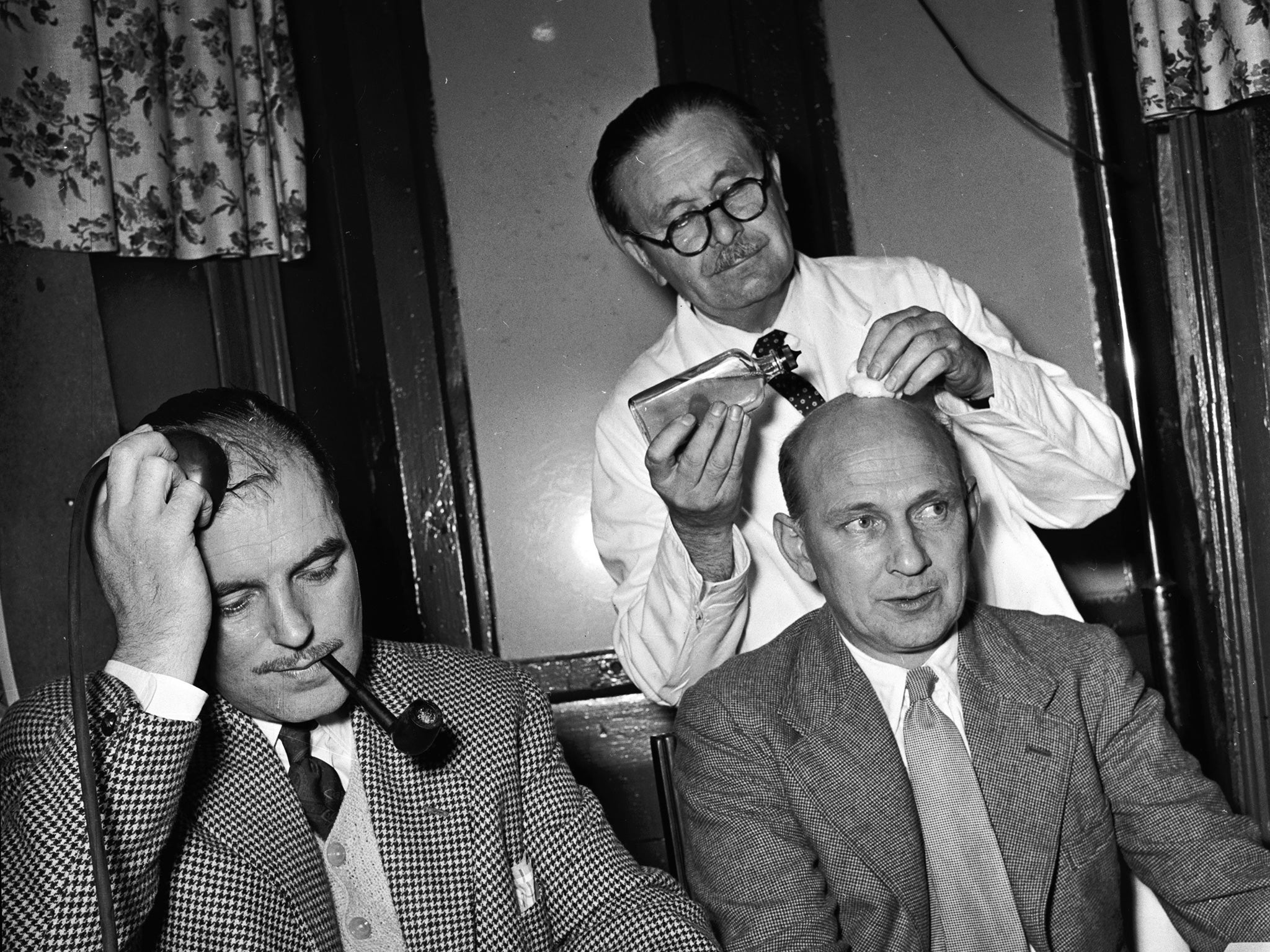

When I was 24, and the hair was fleeing my scalp like a routed army, I was in the habit of visiting a barber near where I lived in west London, who, being gay, was perfectly happy to discuss my trauma openly. His name was Miguel. He came originally from Argentina. He was a great comfort to me.

“Oh Neeck, Neeck,” he used to say. “Don’t worry about it – it will look grrr-e-e-e-a-a-t when I finish wiv it.”

And he would duly wuzz my head with clippers, make some artistic passes around it with a pair of scissors so fine you might not be able, on dull days, to see their points – and then slap my scalp about a bit with his hands to increase circulation.

“But it’s the itching, Miguel,” I would say, plaintively. “It’s not the hair loss so much as the bloody itching. It’s driving me mad. What can I do about that?”

“Leave it to me, my friend,” said Miguel, actually tapping his nose. “Come see me tomorrow, and I will have just ver fing for you.”

So I duly went to see Miguel the next morning and he sold me, for ten quid, a small, unlabelled vial of blue fluid – as vividly blue, now I think about it, as Wayne Rooney’s eyes.

“Is concentrate of Argentinian cow’s placenta,” Miggy informed me, pushing the tenner into his jeans pocket. “I had it made up for you special. Put it on your head after you wash your hair, rub it in for five minutes, and it will keeell ver itching very well in no time. You will see.”

A chap will do anything when he has seen his own death. He will buy concentrate of Argentinian cow’s placenta. He will even spend thousands of pounds to have the skin of his head sewn with hundreds of tiny shrub-like clumps of real hair, to counterfeit the illusion of normal growth, possibly convinced that normal growth will naturally resume now that the silly old scalp has been shown, by proximate example, what to do. Death is awful. It’s worth fighting. But you’re not just fighting death when you do it; you’re fighting real life too.

One of the ordeals of premature balding is the assimilation of new knowledge of how you’re perceived by others. Any bald man reading this will already know what I’m going to say next. Here it comes… When you lose your hair young, you are marking the end of that period in life during which others see you as “a man”. That’s it. It’s over. You are now not a man but a bald man; a prematurely bald man, if you want the footnoted edition. That’s your new identity. That’s your genus. That, in a highly-polished nutshell, is not who but what you are. (And “what” always comes before “who” where baldies are concerned.)

There are ribald variations, of course. On first contact, you might register to those with half-decent manners as “a prematurely bald man”. To the rest you are a slaphead, Kojak, cueball, chrome-dome or spammy. Egg bonce is another one. Shinehead a semi-respectful Jamaican version. “Baked bean” is one I often cop from members of my own family. On very rare occasions, you can be “Duncan Goodhew” (“Sinead O’Connor” on the rarest occasions of all).

That’s OK. It’s not that hard to get with the programme, unless you harbour some irrepressible need to be identified as a sickening long-haired poet: you’re a chrome-domed spamhead Kojak, and that’s all there is to it. Embrace it. Love it, baby. For that is your special message to the masses: baldness. What do you convey to others? Scantness of barnet, and that’s it. Baldness is the bald man’s only meaningful burden, in the sense that it’s the only meaning that other folk are prepared to take from a bald man.

And you do learn to live with it, in due course, even as a young man, as we all must learn to live with not only who we are but how we are perceived. I am a white middle-class male, so my burden is a light one, relatively speaking. I can manage a little excess spam. But there’s a catch, which can be crippling: learning to live equably with one’s new social identity as a cueball does not alter the fact that you have also, whether you like it or not, seen your death. And once you have seen it, you cannot un-see it.

And this is Wayne Rooney’s problem.

I am not, as it happens, a Manchester United fan, but I have over the years been a keen student of Wayne’s head. I have been prepared to set aside the imperatives of partisanship in favour of common empathy. I know what he’s going through every day and I know – as he himself knows – that he has not been the same player since the hair started to regrow so mysteriously on his head, as it began to do two or three seasons ago.

Everyone puts the one-time boy wonder’s decline as a player down to the departure of Sir Alex Ferguson and the chaos into which the second richest club in the world was subsequently thrown. But it isn’t that. Believe me. His decline predates the gaffer’s retirement. It’s Rooney’s own hubris that has brought his football back to the mortal level. His descent is down to the hair-replacement therapy that has carpeted his once-incipient gleamer with a shagpile of new follicles. Rooney has denied the spectacle of his own death.

You can’t do that and expect to be happy. You can’t even expect to play football as well as you used to. Such existential tinkering will only take half-a-yard off your pace and compromise your decision-making. Your spontaneity will be choked too. And as for your vision, well – when your gaze snags on every reflective surface you pass, on the hopeful off-chance that, for once, your pate will not be reflecting light like the mirrors on the Hubble telescope, then how will you ever possess the vision to sense the late runs of deep-lying midfielders? Rooney is as fit as a butcher’s dog from the head down. Up top he is a mass of vulnerabilities and preoccupations.

Can he be fixed? Of course he can – and in time for Euro 2016 too, if he has the will. He must not shy away from the sight of his own death. He must not cover it up with a carpet of new hair. And for that very reason it might be helpful to him to read the 16th-century essayist (and notable Renaissance baldy) Michel Eyquem de Montaigne on the subject of death, and digest what he has to say about the necessity of making an accommodation with the inevitable, howsoever you meet it. Anything is better than denial.

The England captain might even get away with just reading Sarah Bakewell’s brilliant Montaigne biography, How To Live: A Life of Montaigne, in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (Chatto & Windus). It’s a brilliant piece of work and rather more readable than the actual words of the charming but rambly be-ruffed tower-bound thinker and feeler. It is as important for footballers as it is for the rest of us to take the positives where we can.

What does Montaigne say, precisely, about making a full and affirmative accommodation with death? An awful lot, actually, and not always all that comprehensibly. But he does write: “Where death waits for us is uncertain; let us look for him everywhere. The premeditation of death is the premeditation of liberty.”

What he is saying in essence is, look your death full in the face – as indeed we may gaze upon the face of the rising moon – and we will find liberty in life: the freedom to run, turn, shoot and do bicycle kicks; the freedom to be ourselves without hindrance; the freedom to be fully within the ongoing moment of life, rather than mired in the truckling dread of extinction. Stop pretending, in other words, that you haven’t seen your death.

That’s what Montaigne says. What I say is: shave it off, Wayne, face up to your moon and learn to live again. It’ll do wonders for your football – and for everything else in life, too.

Nick Coleman is the author of ‘The Train in the Night: A Story of Music and Loss’ (Vintage) and the forthcoming novel ‘Pillow Man’ (Jonathan Cape), published on 6 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments