Younger, whiter and more British: The changing face of terrorism in the UK since 9/11

Exclusive: ‘The threat and profile of terrorists has completely changed,’ senior officer tells Lizzie Dearden

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the year of the 11 September 2001 attacks, the average terror suspect in Britain was a non-white, non-British man above the age of 30. Two decades later, he is likely to be white, British and far younger.

The statistics, which began to be collected following al-Qaeda’s attacks on the twin towers, tell the story of the changing face in terrorism in the UK, reflecting the shift from mainly from Northern Ireland-related terrorism to jihadi groups including Isis, and the recent rise of the far-right.

Dean Haydon, senior national coordinator for Counter Terrorism Policing, has witnessed the evolution first-hand. He became an officer in 1988, seeing IRA bombs go off outside an army recruitment centre in Wembley and at the Staples Corner interchange.

By the time of the July 2007 London bombings, he was part of the Metropolitan Police’s anti-terrorist branch – as it was then known – and has stayed mainly in the sector ever since.

Mr Haydon says the most recent changes have been the rise of the extreme right-wing and “self-initiated” terrorists who act alone. “The threat and profile of terrorists has completely changed,” he adds, going on to say: “We are dealing with individuals that are self-radicalised, that are looking at extremist materials online... they’re not waiting for some kind of direction or approval from above.”

Not only have terrorists become less trained, less prepared and less networked, they are also becoming younger, more British and more white. And the changing profile and tactics of terrorists mean stopping them is harder, Mr Haydon says.

In the year to September 2002, only three terror suspects under the age of 18 were arrested in Britain, whereas the number was 25 in the 12 months to this September.

Almost two-thirds of convicted terror offenders used to be aged 30 and over. Now it’s only a fifth.

The proportion of terror suspects who define themselves as British has jumped from less than a third to 80 per cent in the same period.

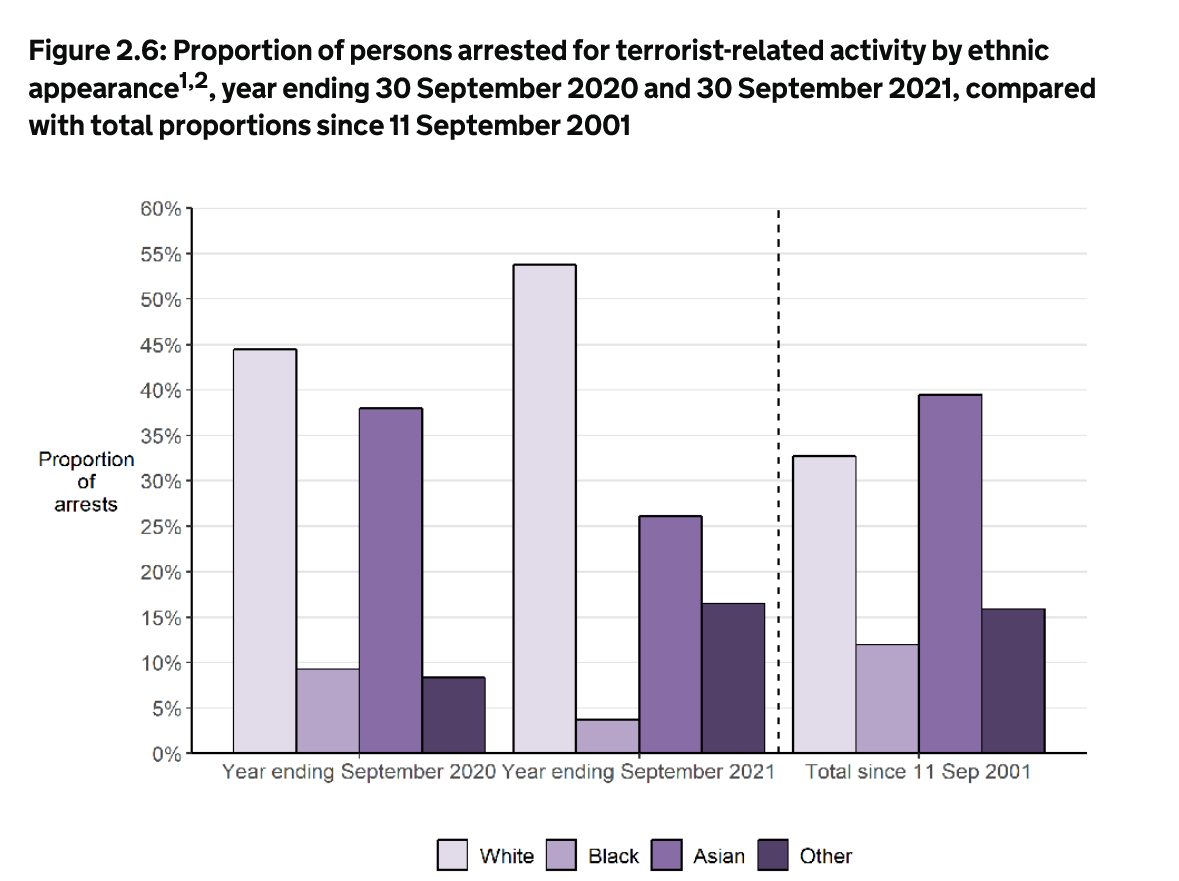

Racial demographics have also changed dramatically. From 2001 to 2004, most people arrested on suspicion of terror offences were white, but then suspects of Asian ethnicity overtook, making up the largest proportion until 2018.

But now the number of white people arrested on suspicion of terror has exceeded Asian people for the fourth consecutive year.

Around 13 per cent of cases being handled by counterterror police in Britain are from the extreme right, while the bulk remains jihadist.

But in the Prevent counterextremism scheme, which aims to stop people from being drawn into terrorism, most referrals are labelled as holding a “mixed-unstable or unclear ideology”.

“People consuming material online in the early days were pretty much stovepiped in relation to those groups, like al-Qaeda or the IRA, whereas now you see youngsters experimenting with all of it because there's so much extremist material online from different organisations,” Mr Haydon says.

“Part of that is to seek instructions on how to commit an attack or build a device; some of it is interest; some of is kids growing up; some of it sharing and disseminating for a bit of kudos - ‘look what I’ve found’ sort of thing - and some of it is being used to desensitise people.”

The increase in online terrorist propaganda has resulted in a rise in prosecutions for collecting or disseminating material that could be useful for attacks, which are now the most common terror charges in Britain.

In almost every year from 2007 to 2017, the most frequent charge was preparation of terrorist acts, including attack plots and travelling to fight abroad.

Mr Haydon says the internet had “changed terrorism completely”, by making more ideological and instruction material available, and allowing encrypted online contact rather than in-person networking.

Previously, people who wanted to join jihadi organisations mainly aspired to train or fight abroad.

He explains that groups like the IRA and al-Qaeda had hierarchical command structures, where “somebody at the top would approve and say ‘yes, I want you to do that attack in this place’”.

Complex plots such as 9/11 and 7/7 involved “an awful lot of planning” over months or years, involving senior figures assigning people to roles, and deploying them accordingly.

But the emergence of Isis in 2014 changed everything. The group, which evolved out of al-Qaeda in Iraq, originally called on supporters to travel to its new “caliphate”. As western nations started making that more difficult and bombing Isis territory, the group changed tack.

In a speech released on 21 September, an Isis spokesperson called on followers to “defend the Islamic State … from your place wherever you may be”.

They called for lone-wolf attacks on military, police and security targets, but also gave permission to kill any “disbelievers” in countries that had joined the US-led coalition against Isis.

Mr Haydon said the speech “changed the threat completely” in the UK, sparking a wave of homegrown terror plots from Isis supporters – including some who had been prevented from travelling to Syria.

British self-initiated terrorists have since become the country’s greatest threat, with al-Qaeda and Isis popularising “martyrdom”, and Mr Haydon said attackers now mostly want to die in the act.

Several jihadi attackers have worn fake suicide vests to ensure they are shot dead by armed police, while far-right terrorist Darren Osborne told survivors of his van ramming in Finsbury Park: “I’ve done my job – you can kill me now.”

There has also been a shift in targeting, away from landmarks, government and military locations and infrastructure, to seemingly random public places like Streatham high street and a quiet Surrey suburb.

Mr Haydon says the changing terrorist profile and tactics in Britain has made attacks harder to detect and stop.

“The terrorism threat and the challenge that we all face trying to stop attacks has become ever more difficult,” he adds. “Our collective challenge is far more difficult than it has ever been.”