Talha Ahsan: Behind bars for six years without charge and a family losing faith in the rule of law

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

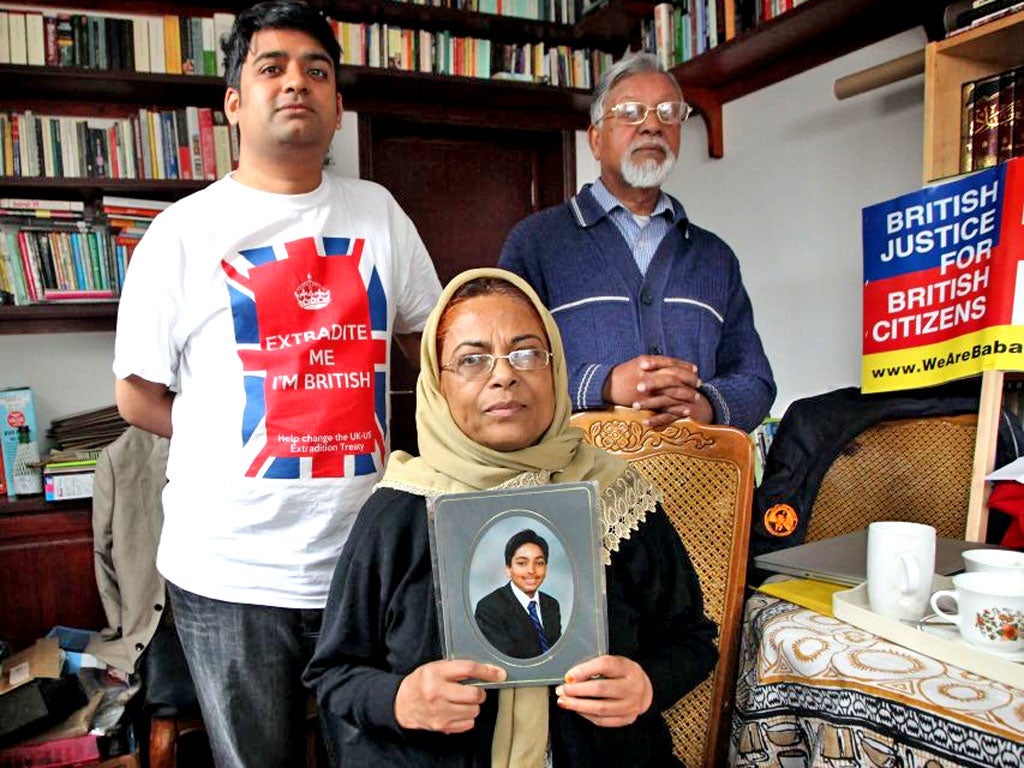

Your support makes all the difference.The police came for Talha Ahsan six years ago. Hamja, his younger brother, was upstairs in the family’s terraced house in Tooting, south London, when officers stormed through the back door.

“By the time I came down both my parents were in tears,” Hamja recalls, sitting in the same room where the police first smashed their way into his home. “They just told me that Talha had been taken away.”

When the initial shock wore off, his parents began to console themselves with the idea that, whatever their son may or may not have done, he would at least be able to go to a court of law and try to prove his innocence.

But Talha has never been charged. Instead he has been held in a British prison for the last six years following a request from the United States who want to prosecute him for allegedly running a pro-Islamist website.

Under the extradition agreement signed with Washington, American prosecutors are under no obligation to provide any prima facie evidence showing wrong doing before they submit an extradition request. The British police – who do have to provide evidence if it is the other way around – cannot refuse, nor can the accused challenge the extradition request in a British court.

The only allegations against Talha so far are contained within a remarkably evidence-light 14-page indictment filed at a court in Connecticut. But that has been enough to keep Talha behind bars ever since. If he is successfully extradited, the likelihood is that the 33-year-old will be sent to a so-called Supermax prison where inmates spend 23 hours of the day in solitary confinement. It is a regimen that many, including a senior UN rapporteur, have described as being tantamount to torture.

In recent years Britain’s extradition agreement with the United States has come in for heavy criticism, especially with the attempts to extradite suspected cyber criminals such as Gary McKinnon or Richard O’Dwyer.

But those accused of terrorism-related offences have elicited much less sympathy, both from the public and the media. It is not lost on the Ahsan family that while Gary McKinnon is confronting a sentence in the US that is even longer than Talha’s, he has at least been granted bail to fight his extradition.

“All these basic legal precedents have been trodden on,” says 31-year-old Hamja, who gave up hopes of becoming an art curator to run his brother’s campaign full time. “Habeas corpus, that’s chucked out the window. Presumption of innocence, access to family, protection from torture – out the window. And of course there’s the government’s very first duty, to protect its citizens. That’s been chucked out of the window too.”

Perception is clearly part of the problem. Talha Ahsan and his co-accused Babar Ahmed, have had their cases lumped in with some much more unsavoury figures. When lawyers took their case to the European Court of Human Rights earlier this year – to argue that Supermax prisons would be a breach of their human rights - his fellow defendants were the hook-handed cleric Abu Hamza and two men arrested before September 11 on allegations that they had a direct involvement in the 1998 US embassy bombings in east Africa. When that challenge was thrown out the popular press ran headlines labelling all five as Muslim fanatics.

“It’s obvious that the tabloid media, as is expected, doesn’t treat us the same,” concludes Hamja.

That is not to downplay the seriousness of the allegations against his brother. According to American prosecutors he and Babar Ahmed used online aliases to help run a series of pro-Islamist militant websites that worked under the banner of Azzam Publications. One of the site servers was based in Connecticut allowing prosecutors to file charges in an American court.

Azzam shut down shortly after the September 11 attacks – as much a hostage to timing as anything else. Prior the al-Qa’ida’s assault on New York it was one of many pro-violent jihad websites. It may have espoused a millenarian and unpleasant world view, but whether it was illegal or not is difficult to tell. Named after the famous jihadist theologian Abdullah Azzam, it publicly supported the Taliban and jihadists in Chechnya – neither of whom were deemed terrorist entities at the time (the leader of the anti-Russian Chechen movement still resides in London). But after 9/11 US prosecutors wanted to arrest anyone involved in it, even once it had shut down.

Talha’s family believe the evidence of his involvement in Azzam is flimsy at best. “Firstly it’s never been established in a court of law whether Talha was on that website or involved in any way,” explains Hamja. “We’ve seen no evidence. The website itself ran from 1997 to 2001. What that basically means is that he’s been detained for a defunct website that was offline for five years at the time of his arrest.”

Their suspicions are compounded by the fact that Talha’s co-accused – Babar Ahmed – was viciously assaulted by police officers in custody. The Metropolitan police were forced to pay-out more than £60,000 in damages when Ahmed’s family brought a successful civil claim. Talha was arrested shortly after Ahmed and yet no British prosecutors opted to bring charges against two men who have supposedly committed crimes on UK soil.

But more importantly, Talha’s family say, is the fact that he had never shown any evidence of holding extremist beliefs. “He’s a devout Muslim, but that’s not a crime,” says Hamja.

The family describe him as a shy, academic man. He excelled in school and went to Dulwich College, a private school, where he taught himself Arabic at the age of 16. He went on to study the language at the School of Oriental and African Studies and spent a year in Syria.

“When he was a boy he used to eat and read at the same time,” recalls his 67-year-old mother Farida. “I would try to tell him to stop but he would just say ‘Mummy, I can’t time is precious’”. America’s so-called War on Terror clearly upset him. He was a regular campaigner for those held without charge at Guantanamo and could often be seen at protests. But his family say he eschewed any form of violence.

“Talha isn’t like that,” insists Hamja. “He likes Radio 4, the Beatles and Ted Hughes. He listens to Absolute 90s radio and talks about all these indie bands from the 90s. When I went to see him the other day he was listening to the Happy Mondays and reading [Zadie Smith’s novel] White Teeth.”

In 2009 he was diagnosed with Aspergers, the same autistic spectrum syndrome that Gary McKinnon suffers from. Throughout his time in prison he has written some hauntingly beautiful poetry which is now being used to publicise his cause. On Saturday his family are holding a fundraiser evening which will feature much of his poetry.

Over time the camp of supporters surrounding Talha Ahsan has grown. Politicians, human rights groups, lawyers and artists have all flocked to his cause. Two of his most public supporters are the young actor Riz Ahmed and the Scottish poet AL Kennedy.

“The fact that detention without trial can happen at the behest of a foreign government and is then authorised by our own government without seeing any evidence against the person in question is particularly horrific to me,” says Ahmed, who often reads Talha’s poems in public. “The campaign isn’t saying release these men. It’s saying we want British justice for British citizens. If these people have committed crimes on UK soil they should be tried here. That’s not a huge ask.”

For Talha’s family there is little they can do but wait. A last appeal is now winding its way through the European Court of Human Rights. If that is lost his only hope rests with the Government and whether Ministers are willing to reform the current extradition agreement with the United States.

Talha’s mother Farida, whose family had to leave India during partition and flee to Bangladesh, is not optimistic. “I have no confidence, faith or respect for politicians wherever they are,” she says. “My husband wanted to settle here because it was safe. Britain was a disciplined place, there was rule of law. But look what has happened to the rule of law now. What has happened to Britain? If my son has done something wrong, fine, charge him here and put him in a British court.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments