Shamima Begum: Number of people stripped of UK citizenship soars by 600% in a year

Critics say Sajid Javid has taken ‘easy way out’ by using power against Shamima Begum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

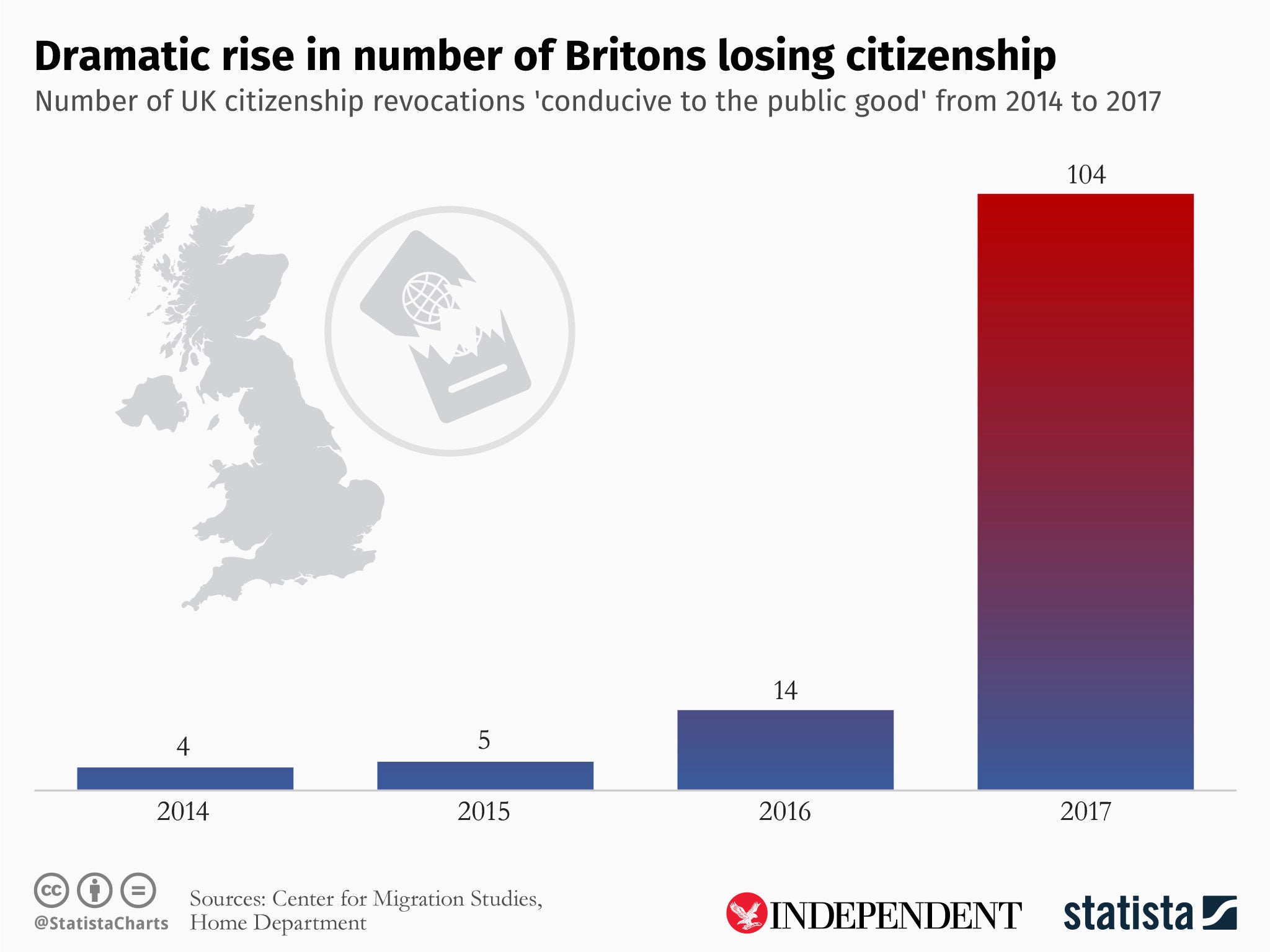

Your support makes all the difference.The government’s use of controversial powers to remove British citizenship has soared by more than 600 per cent in a year.

Shamima Begum is one of more than 150 people subjected to the measure for the “public good” since 2010.

The removal of citizenship means the 19-year-old has no right to enter the UK or gain a British passport, and cannot request assistance to leave the Syrian camp where she is currently detained with her newborn son.

Ms Begum’s family are to launch a legal challenge, and their lawyer said the teenager, who could have automatic Bangladeshi citizenship through her mother, was born in the UK and had never been to Bangladesh or possessed a Bangladeshi passport.

Official statistics show citizenship deprivations were used only a handful of times a year, until they rocketed from 14 people in 2016 to 104 in 2017.

The Home Office declined to give a reason for the dramatic increase, and said it could not provide a breakdown of how many Isis members were involved or the justification for each case.

The government has argued that citizenship deprivations protect the public, but critics accused it of abdicating responsibility and setting a “dangerous precedent”.

Lord Anderson, the former independent reviewer of terrorism legislation, said Ms Begum could have automatic Bangladeshi citizenship through her mother but her status would have to be proven at any appeal.

“She’s got no real connection to the country to which the home secretary is saying she now exclusively belongs,” he told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

“We should take responsibility for our own citizens, at least in circumstances where they have spent their lives here.

“We are responsible for dealing with the consequences, however unpalatable that might be.”

Lord Anderson suggested that stripping citizenship was a “far simpler” option for the government than letting Ms Begum return, adding: “You don’t need the permission of the court, you sign an order and you don’t have to deal with them. You simply pull the rug out from under them and they can’t come back.”

The crossbench peer, who is also a practising barrister, warned: “It could be seen as an abdication of responsibility to remove citizenship from someone who was radicalised in our country, who left when she was a child, and who we are relatively well-equipped to deal with, whether by prosecution or deradicalisation.”

Ms Begum told ITV News she was “shocked” by the move and suggested she would explore how to gain Dutch nationality through her husband, who is an Isis fighter from the Netherlands.

Her family’s lawyer, Tasnime Akunjee, told The Independent they would launch a legal challenge and accused the government of leaving Ms Begum effectively stateless.

Another lawyer, Fahad Ansari, who represented two alleged Islamists of Bangladeshi origin who won appeals against being stripped of British citizenship last year, said Ms Begum was a “British problem”.

“She was not born or raised in Bangladesh, she was not radicalised in Bangladesh, it all happened in the UK,” Mr Ansari said.

“It just seems that it’s an easy way out for the home secretary without having to prove her criminality in a court of law.”

The British Nationality Act 1981 gave home secretaries the power to deprive people of British citizenship if their presence was “not conducive to the public good” or if their nationality was gained fraudulently.

But in 2014 the government extended the law to let the power be used even when people would be made stateless, if they have “conducted themselves in a manner seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK”.

“In practice, this power means the secretary of state may deprive and leave a person stateless if that person is able to acquire (or reacquire) the citizenship of another country,” official guidance states.

Hailing the change in November 2014, the then home secretary Theresa May said the power had been used because of terrorist activity in the “overwhelming majority” of cases.

However, the revoking of British citizenship in the case of Shamima Begum has been widely criticised.

Diane Abbott MP, Labour’s shadow home secretary, said “fundamental freedoms do not need to be compromised” for public safety.

“If the government is proposing to make Shamima Begum stateless, it is not just a breach of international human rights law but is a failure to meet our security obligations to the international community,” she said.

Conservative former minister George Freeman criticised the move as a “mistake” that will set a “dangerous precedent”.

The Liberal Democrats called for Ms Begum to be allowed to return to the UK to face prosecution and “learn lessons as to why a young girl went to Syria in the first place”.

Human rights campaign group Liberty said revoking a person’s citizenship was a power that “must not be wielded lightly”.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “In recent days the home secretary has clearly stated that his priority is the safety and security of Britain and the people who live here.

“In order to protect this country, he has the power to deprive someone of their British citizenship where it would not render them stateless.

“We do not comment on individual cases, but any decisions to deprive individuals of their citizenship are based on all available evidence and not taken lightly.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments