Scandal of our privately fostered children

Charities say there are hundreds of cases of abuse at any one time in a modern form of slavery first revealed by the IoS

Inadequate regulation of private fostering in Britain is leaving hundreds of children in danger of abuse, welfare agencies have warned.

Such children – many brought to the UK from abroad – remain "invisible" to the authorities, 10 years after the outcry that followed the murder of Victoria Climbié, the eight-year-old from Ivory Coast who was tortured to death by her great aunt and her aunt's partner.

Figures revealed in an investigation by the BBC's Newsnight programme show there are about 500 cases of suspected neglect or abuse of a privately fostered child at any one time in Britain. About half of these involve children from abroad.

But the head of the welfare agency behind the research, Andy Elvin of Children and Families Across Borders, said: "That is only a small minority of the cases that are out there. There are probably several hundred more of these a month going on that we just don't know about.

"If Victoria Climbié was coming over today, she would get through the border in exactly the same way – and the questions that weren't asked then wouldn't be asked now."

Last February, The Independent on Sunday revealed that an estimated million children have been privately fostered at some point in their lives, the vast majority in secret, without the knowledge of the authorities.

Overall, the Government now estimates there are at least 10,000 children in Britain growing up in informal foster arrangements unknown to local authorities.

Legislation since the death of Victoria Climbié requires councils to be pro-active in investigating possible cases – but the inspection agency Ofsted reported in 2008 that more than a quarter of local authorities had inadequate arrangements for monitoring private fostering.

Foster parents themselves are supposed to notify councils if they are informally caring for someone else's child. But it is estimated that only one in eight does so. Failure to notify rarely, if ever, results in prosecution.

In practice, private fostering often works well – but the worst cases seen by Jim Gamble, head of the government's Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre, involve benefit fraud or other forms of exploitation. He said: "It is like a form of modern slavery. You bring a child in from a country not your own. You don't pay them; you don't really look after them. They clean for you as they get older, then perhaps they are used for domestic servitude."

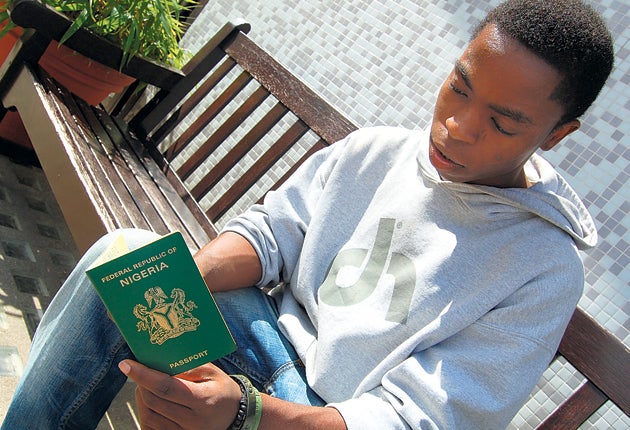

Tunde Jaji, now 24, was brought to London from Nigeria at the age of five to live with a woman he called his "aunt". His case was not as serious as Victoria Climbié's, but he says his guardian never showed him any affection. He says she used to hit him, verbally abuse him, and force to him to perform chores she didn't demand of her own children.

"She used to get me to clean the garden before I went to school. She used to get me to take the other kids to school. She wouldn't make an effort. She wouldn't come to parents' evenings and stuff like that.

"If I didn't clean the stairs or the kitchen properly she used to say I was evil, or that's why my mum died."

He says the woman told him that both his parents were dead. Later he found out that wasn't true – and that his "aunt" was no relation at all.

By law, councils must assess private fostering arrangements. But there is no evidence that Tunde's council, Haringey, in north London, ever suspected he was fostered – even though the names of carers given on various documents did not match, and the family was contacted by social services for other reasons.

When Tunde was 18, he discovered he had no official papers, and no right to remain in Britain. It was only with the help of his former special needs teacher, Lynne Awbery, that he was able to go to university – and, eventually, acquire British citizenship.

Ms Awbery said: "He was identity-less and he was living in this sort of limbo-land. He couldn't go back to where he came from because he had no documents, and he couldn't go forward because he couldn't access anything.

"If this family were known to social services, why didn't they ask questions? Who is this child who doesn't match any of these surnames that you have had? There just seem to be masses of questions that people could have asked."

Since Tunde grew up, Haringey has set up a dedicated private-fostering team to monitor such arrangements. A spokeswoman said the council had helped Tunde gain permission to stay in Britain.

While in opposition, the new Children's minister, Tim Loughton, called for private fostering to be made "a fully regulated activity, with penalties for people who fail such children".

He has now commissioned a review of child protection from the social work expert Professor Eileen Munro – with initial findings due to be published at the end of this month.

Last week, his department said it was "looking at what more can be done to increase considerably the numbers of privately fostered children who are known to local authorities."

But no decision has yet been taken on setting up a register of private foster carers, as some welfare agencies want.

Tim Whewell reports on private fostering for Newsnight, on BBC2, tomorrow and Tuesday at 10.30pm

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies