SAS inquest: Deaths of three soldiers down to a catalogue of 'gross failures', court concludes

Coroner criticises lack of planning, faulty equipment and 'chaotic' response

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The three British soldiers who died during a selection test for the SAS were killed as a result of a catalogue of “gross failures” by one of the military’s elite units, their inquest concluded.

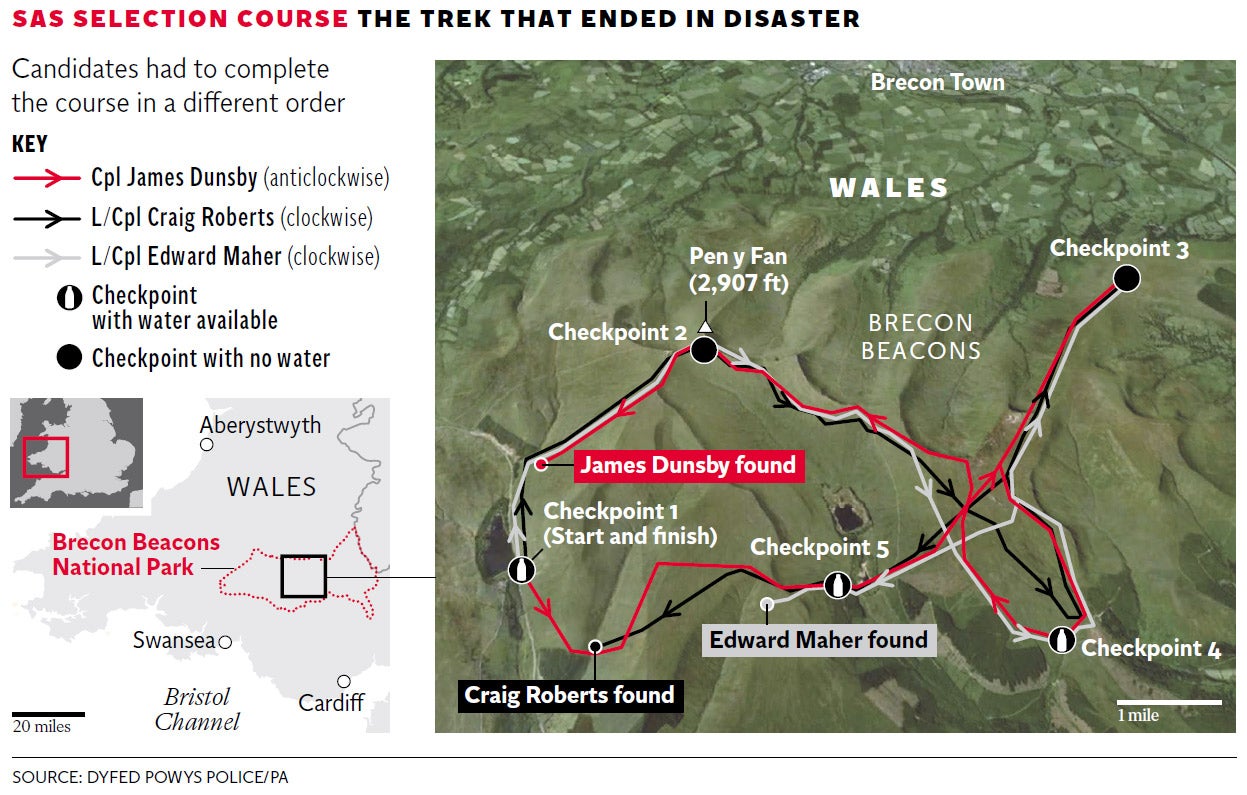

Lance-Corporals Edward Maher and Craig Roberts and Corporal James Dunsby died from the effects of heat exhaustion after a series of “serious mistakes and systemic failures”, coroner Louise Hunt ruled in Solihull.

The three were taking part in a 26-mile endurance march in the Brecon Beacons in Wales in searing temperatures when they collapsed. Two of the men – Maher, 34, from Winchester, and Roberts, 24, from Llandudno – died on the hills. The third soldier, 34-year-old Dunsby from Trowbridge in Wiltshire, collapsed but died two weeks later in Birmingham’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

In a damning verdict, the coroner concluded that the three deaths were the consequence of “neglect” by the Army, which failed to follow its own rules. She said if the officers and junior ranks supervising the march in July 2013 had obeyed Ministry of Defence guidelines, the march would have been stopped six hours into the test when the first troops began to collapse with heat exhaustion. Had it been stopped, all three men would still be alive.

However, the inquest heard evidence that the supervisors were unaware of the guidelines, drawn up after the death of a Royal Marine in similar circumstances in 2009. Another supervisor claimed he had only “skimmed” it – while others argued the guidelines were not applicable.

Ms Hunt criticised the Army for carrying out an “inadequate” risk assessment of the arduous selection test, which was “not fit for purpose”. The test failed to take into account that it was taking place on one of the hottest days of the year, with temperatures reaching more than 31C.

Despite the heat, there was insufficient water set out along the route of the march and the assumption that men get water from streams proved mistaken, as many had dried up or were “murky”.

Those in charge on the day, who have not been identified for security reasons, showed a “general lack of understanding of heat illness and the risks posed to candidates”, Ms Hunt said. As a result, when the first two soldiers dropped out showing clear symptoms of heat illness, they failed to stop the test.

A tracking device carried by each soldier on the march to indicate their position was known to be faulty but was still relied upon to spot if a man was slowing down through illness or had collapsed and stopped altogether.

Ms Hunt criticised the MoD’s reliance on the tracking device.

Medical experts said there was a “golden hour” to treat victims of heat exhaustion but, in the worst case, LCpl Maher’s collapse wasn’t noticed until one hour and 44 minutes later. The response time in LCpl Robert’s collapse was also over an hour. The inquest heard evidence that the tracker had a “slow man” facility that highlighted struggling candidates, but that it had been turned off because it “crashed the whole system.”

Coroner Hunt also criticised the lack of medical planning. Supervising staff were not warned or trained how to manage heat illness or report cases when they saw it. The medical plan wrongly identified the closest hospital and failed to alert the NHS or a rescue helicopter about the march.

Communication problems in the Brecon Beacons meant 999 emergency calls had to be made repeatedly to report men in danger. Some paramedics were given the wrong co-ordinates to find the dying men. The response to casualties was “chaotic”, she said.

Other failures also included the Army not knowing the troops taking part in the test were reservists who had not taken part in a series of forced marches the week previously to acclimatise them in the build-up to the final strenuous test.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.