‘I was just a kid’: SAS veteran speaks out, eight decades on from Second World War service

Exclusive: Special forces played a vital role in Allied efforts during the war, and became the source of many of its greatest tales of derring-do. Jack Mann was there, writes Jon Sharman

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Don’t talk to me about the sand – I’ve had it in the mouth, in the ears, in the eyes, in the nose, everywhere. Terrible. In my food, particularly.” The distaste in Jack Mann’s voice is plain, some eight decades on from his service in an elite band of desert raiders during the Second World War.

Mann, 94, is one of the last British survivors of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG), a reconnaissance and raiding force that operated in north Africa including alongside David Stirling’s fledgling Special Air Service (SAS). The group used modified jeeps and trucks to trek across the desert behind enemy lines, gathering intelligence on the movement of hostile units.

But it was not just the enemy these early special forces teams had to fight – the Sahara’s harsh winds and sand could take their toll as well. Speaking at the Victory Services Club near Marble Arch, Mann tells The Independent that while being treated in hospital for an injury he encountered one unfortunate New Zealander “covered in desert sores”.

“The surgeon asked the nurse to give him a bath before he could look after him. But in half an hour she was back. She came into the ward and said, ‘I can’t wash him, I can’t see it’ – all the desert sores, it was terrible to look at. I was feeling better and I said, ‘I’ll give him a bath’. They couldn’t believe it, I was still a young lad then. All my life, since I was in the army, nothing worries me, I’ll help anybody.”

His kindness earned him an invitation to New Zealand and after the war he made nine trips there, searching for old comrades. “I met two of them, and I met a lot of widows. All the rest had gone,” he says.

Having joined the army straight from school at 17, Mann was among the LRDG’s youngest members. He was a radio operator, wrestling with crystal sets to maintain communications over huge distances. “When you’re receiving, you need complete peace because you’re on a fixed frequency. But on that frequency there might be three, four, five, six other stations from different countries or the same country”, he tells The Independent.

“You have to listen for just one sound. It’s double-coded so you have to decipher it. You have to take away the sounds of the other stations, the atmospherics – the wind and crackles you hear on your radio. All sorts of noises. You do your best, and if it doesn’t come one way, you move your aerial until it gets through.

“People used to say, ‘Just let him work’. Once, somebody came over to me, I didn’t know who it was, but it was a high-ranking chap – and I told him to f**k off. I heard the conversation [afterwards], somebody shouted, ‘No, no! Just let him work’.”

The small special forces groups were close-knit, with officers and men on first-name terms. “We were all the same, there was no question of being an officer and not an officer. There wasn’t any distance,” Mann says. His elder comrades wore long beards, he says, but as a teenager he could not. “They told me to put some chicken s**t on it to make it grow.”

Later in the war, when he served with the Special Boat Service (SBS) and SAS, that familiarity would get him into trouble. “The nephew or the cousin of one of the commanders came on the trip and wanted to see how we did things,” he says. “It was my turn to cook, and he asked for his food. I said, ‘Come and get it’. He said, ‘You’re speaking to an officer’, and I said, ‘Everybody comes and gets it’. For his impudence Mann was locked up in a military prison by his own side.

But the intelligence that saw him recruited into the special forces in the first place soon came into play, as he outfoxed his gaolers by demanding to be put in contact with Russian authorities. “‘I’m Russian,’ I told them. I’d crossed off ‘Jewish’ on my paybook and I put ‘Russian Orthodox’. So there was a lot of trouble, they called the commander, and this fellow said, ‘Just send him back to his camp’. [My comrades] asked, ‘How did you get back so quickly?’

The tale provides a clue as to why Mann volunteered.

Born in Cairo, Mann is the son of a dentist whose four brothers were also dentists. They had all studied in France before the eldest was sent to Egypt as dental surgeon to the king, he says. That uncle encouraged the others to follow as there was plenty of work, leading one to settle in Alexandria and the rest in Cairo.

“One of my uncles heard about what was going on – the atrocities, the Holocaust. I was just a kid, I didn’t know much about what was going on, I was just studying. I don’t remember if I was angry or not, but I followed his advice, to go and do my bit.”

First, Mann was assigned to the Royal Corps of Signals before intelligence specialists learned he spoke Italian. They tasked him with infiltrating a prisoner of war camp to gather intelligence but he refused, saying his language skills were not good enough to let him pass as Italian. If he was rumbled and his Jewish identity discovered, “that was me gone”, Mann says.

“I said, ‘I joined to fight the Nazis’, and they asked me to wait. Within an hour, they said they’d found a new assignment for me. That’s how I started with the special forces.”

After the sands of north Africa Mann was given extra training and sent to the Aegean, where in autumn 1943 Britain would lead an ill-fated attempt to capture and hold the strategically important Dodecanese islands to keep them out of German hands. The Allied forces suffered heavy casualties. Mann saw action around the Dodecanese and the Cyclades, fighting alongside Greek Sacred Squadron special forces. “We saw people who were very hungry, very poor. Though they had chickens they were not allowed to slaughter them – the eggs were for the Germans.”

A forced evacuation during a conflagration on one island led to a further escapade when Mann, in the scramble to leave, was left aboard a French boat. “I was away for three days. It was very good food, very good wine. As a young boy, to have that food and wine … We had no wine [in the British forces].”

Later, he was trained as an instructor and sent first to Libya, to teach a signals course, and then to Cyprus. He was discharged from the armed forces in 1947. In civilian life Mann was employed in the shipping industry and later in the chemicals division of General Tire and Rubber, which was later part of GenCorp, now known as Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings.

He lives in Pinner in northwest London with his wife of 54 years, Helga, with whom he has four children. The couple regularly go to the gym together and Mann keeps up his languages. His Italian, he says, is now fluent to the point where he has been mistaken for Italian while attending commemoration events for the special forces abroad. Alongside fellow former SAS operators Mann has been deeply involved in remembrance events, travelling numerous times to France and playing a leading role in commemorations at Westminster Abbey. “I’m kept busy,” he jokes.

But his answer to the question of why such events remain important is matter-of-fact. “Because of the lads that died. You pay respect to them.”

The value of special forces

In the early years of the Second World War, Britain’s military hierarchy was in denial. Nazi Germany had developed an effective early-warning radar system that enabled it to detect and shoot down RAF bombers and even dispatch planes to sink a royal navy destroyer sailing 95km (59 miles) off the French coast – but the upper echelons refused to believe it.

In fact, the Germans had two forms of radar known as Freya and Wurzburg, which worked together to track targets. The existence of the former was known to a few British scientists thanks to decrypted Enigma messages and other intelligence, though still denied by senior experts. Conclusive intelligence on the latter – a smaller, portable unit – came in December 1941 when a Spitfire pilot flying a near-suicidal reconnaissance mission brought back the first clear images.

The next month, Operation Biting was approved. A night-time raid by airborne commandos who would parachute into enemy territory, assault a cliff-top radar installation at Bruneval in northern France and steal the Wurzburg equipment there, before being extracted by sea.

It worked. The raiders returned with priceless technology that “absolutely stunned” the British, says Dr Phil Judkins, a visiting fellow at the University of Leeds. The Wurzburg radar was far more technologically advanced than what Britain had deployed until that point, he says; more physically robust, easier to service and capable of outputting more stable frequencies. A strike by special forces was “absolutely necessary”, he adds, and the only practicable way of getting hold of the equipment.

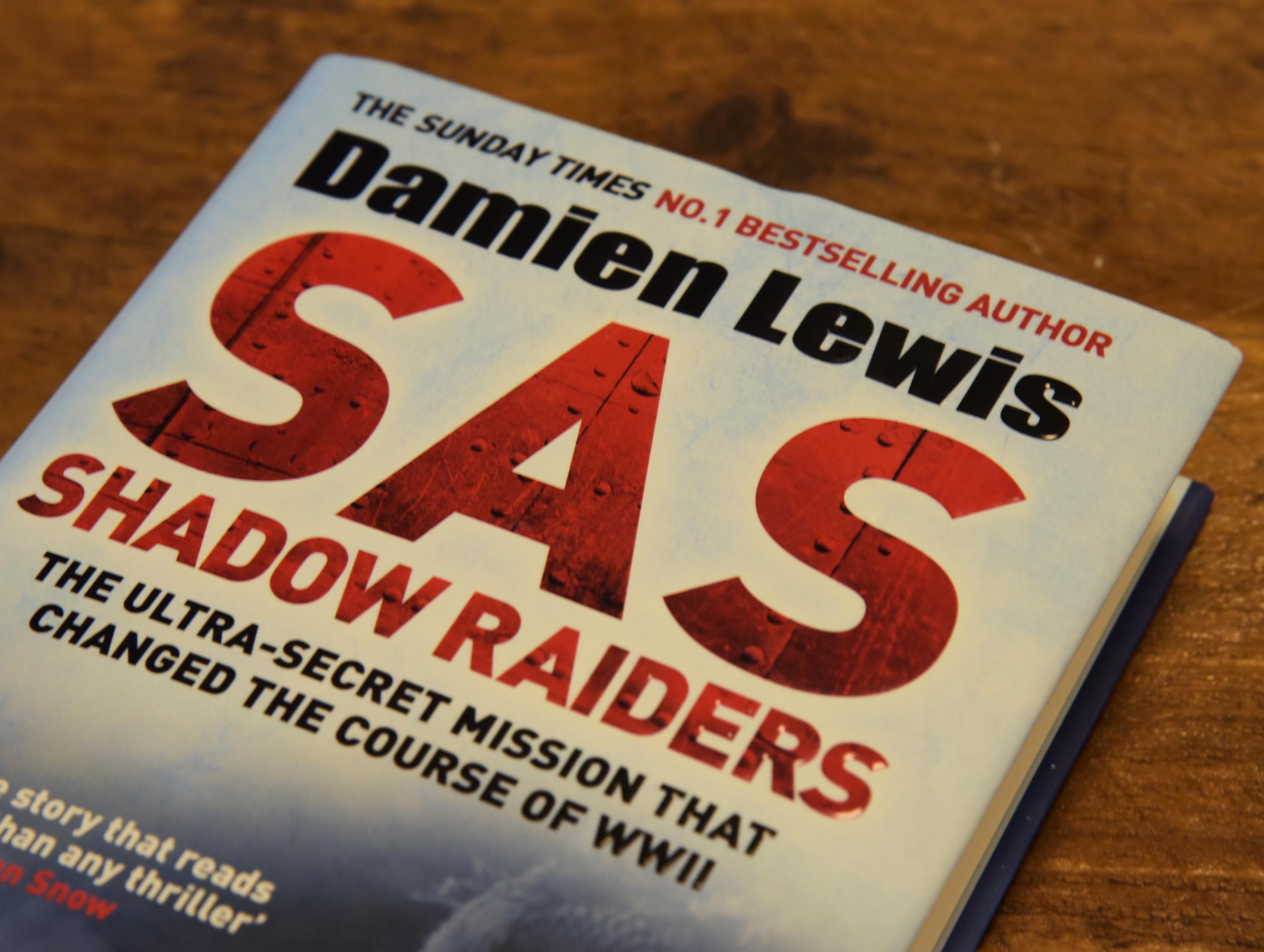

Operation Biting was both a technological and propaganda coup, spurring Britain’s war effort and infuriating Adolf Hitler with its audacity. The story of the raid and its aftermath is detailed in SAS: Shadow Raiders by Damien Lewis, which provides minute insight into how it was conceived, planned and executed – down to the debriefing conversation between its commander, Major John Frost, and Winston Churchill.

‘SAS: Shadow Raiders’ is published by Quercus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments