Rare documents reveal the tragic stories of those who sought official permission to not fight in the Great War

From conscientious objectors drafted into special units, to a wife who begged for her brutal husband not to be spared combat, the records tell many incredible tales

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One mother begged for her youngest son - the last survivor of five - to be spared the killing fields of France. A father, tortured by the thought of the loss of his three boys, is found to have taken his own life. Thousands more pleaded to be kept away from war on the grounds of belief, hardship and injury.

A little-considered aspect of the First World War was revealed today with the publication by the National Archives in Kew, west London, of documents describing the stories of those who sought official permission not to go and fight.

The records of the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal, one of dozens of bodies set up to adjudicate on applications from conscientious objectors to impoverished fathers for a military service exemption, are one of only two surviving full sets of such documents and have now been put online.

Such was the sensitive nature of the files and their potential to damage social cohesion, the government ordered the destruction of all but two sets of the papers after the war.

Of the 8,791 cases considered in Middlesex, only five per cent came from conscientious objectors, undermining the perception that many who sought not to fight were pacifists. Other reasons presented to the tribunals included illness, employment in a protected industry and likely hardship for family members.

Whatever their case, few were successful. The records show that just 26 applicants received a full exemption and 581 were allowed to remain out of the war subject to conditions.

In the vast majority of cases - nearly 7,000 - the appeal was either dismissed or a short period granted for the man to get his affairs in order before heading to the trenches.

But behind these figures lies a fresh insight into life in First World War Britain away from the fighting where, nonetheless, tragedy, division and courage were also to be found.

The Baggs Family

One early morning in September 1918, William Baggs, a pig farmer, quietly closed the door behind him, walking to a nearby river and drowned himself. His body was found by his youngest son, David - one of the three sons whose potential loss on the battlefields of France was too much for Mr Baggs to bear.

An application sent to the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal reveals how two of the farmer’s sons were serving with the British Army in France in 1918.

One of the men, Alfred, had volunteered to fight in 1916 in return for an assurance from the military authorities that his youngest brother David would avoid compulsory conscription and be allowed to run the family farm in the then north Surrey village of Stanwell with his father.

When a letter arrived in May that year requiring David to report for duty, Alfred wrote the tribunal citing the previous agreement. He said: “I should sooner come out here and be killed and have the consolation of knowing I had done the right thing for my brother than see him come out here.”

For William Baggs, by then 60, the thought that his three sons could join the ever-growing list of fatalities emerging from Flanders became a gnawing strain.

A newspaper report of the inquest into his death recorded the testimony of his widow, Annie: “She said that he had always enjoyed good health but was at times depressed and dull. He had worried a good deal about his sons.”

With the future of David still undecided by the tribunal, Mr Baggs awoke one morning and carefully locked the back door of the family home behind him to walk to his death, just a matter of weeks before the Armistice. His wife, who had noticed her husband had not done his usual task of lighting the morning fire, found his suicide note in which he insisted he was “not mad” but could not manage without his son.

The newspaper report added: “[David] went and found his father lying in the river in about three feet of water. He was quite dead.”

All three sons survived the war.

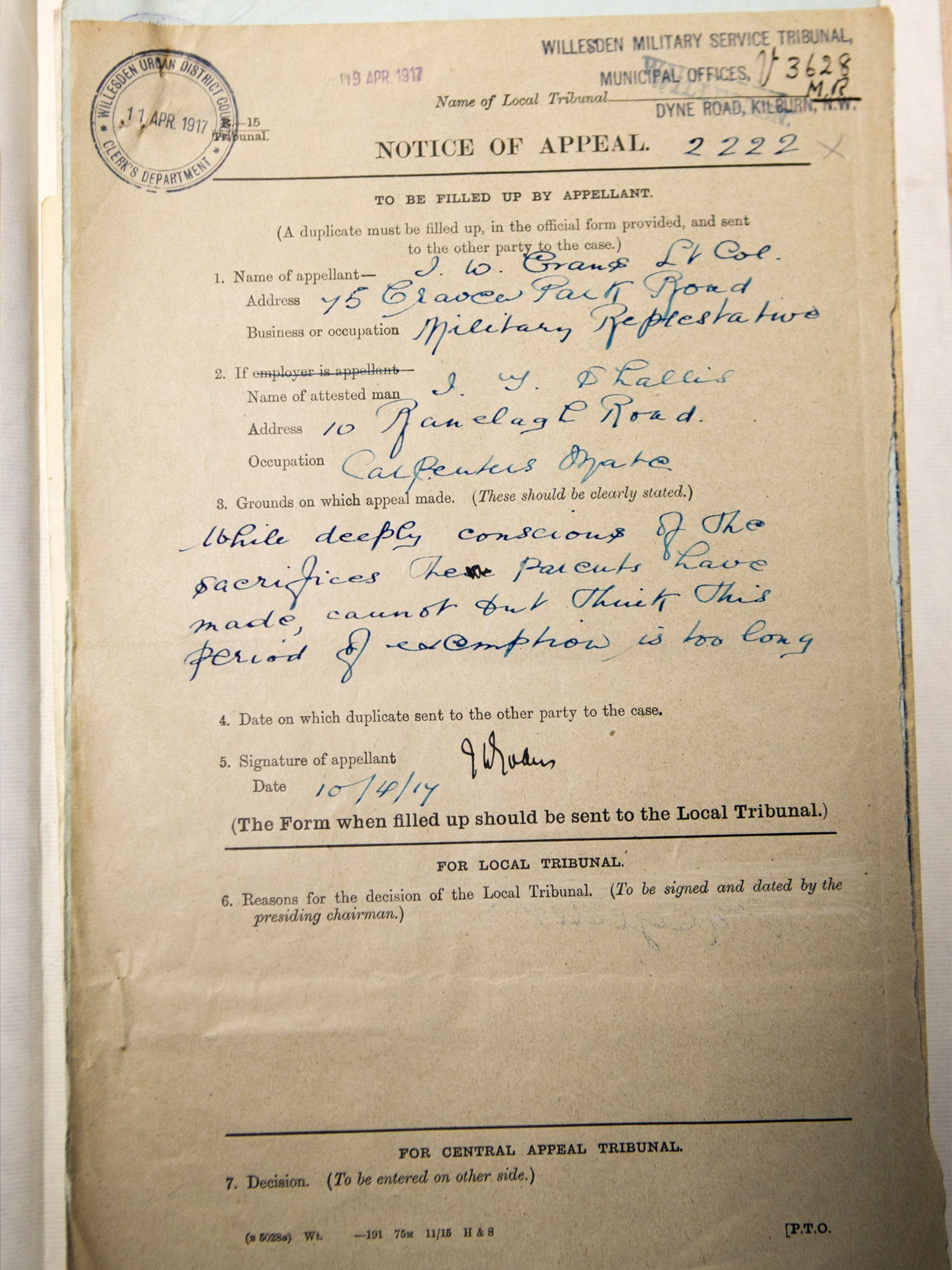

Mr and Mrs Shallis

In the words of a contemporary newspaper report, as far as the London suburb of Harlesden was concerned the “greatest tragedy of the war is the terrible loss of Mr and Mrs George Shallis of 10 Ranelagh Road”.

By early 1917, George and Kate Shallis had borne the loss of three sons, aged from 25 to 19, in various battlefields of the First World War, from the shipping supply routes of the Atlantic to the carnage of Gallipoli. One, 21-year-old Albert, was killed while going to the aid of a wounded comrade.

The newspaper noted: “Last Saturday week [Mrs Shallis] received the sad news of the death of Albert and the following Saturday morning she received a letter telling her that her youngest lad had been killed.”

When shortly afterwards the couple learned that the fourth of their five sons had been killed, John, the sole survivor of the “finely built young fellows standing six feet in height”, applied to the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal asking to be spared military service.

A supporting letter from recruiting adjudicators said: “[We] were of the opinion that the Mother is entitled to the comfort she will obtain by the retention of this last son.”

The documents note that the exemption was granted because of “exceptional domestic position”.

Arthur Walling

One of the 577 conscientious objectors to apply to the Middlesex Appeals Tribunal between 1916 and 1918, Mr Walling was no less sincere and steadfast in his belief that his faith barred him from military service.

In an eloquent letter to the military panel, the railway clerk outlined his grounds for seeking a complete exemption from fighting. He wrote: “I am prepared to suffer anything rather than become a soldier either as a combatant or non-combatant - ie any part of that military movement… I am by no means an obstructionist, having always respected the laws of the land until the one introduced which conflicts with my vow to God.”

His pleas fell on stony ground and he was ordered to join one of the non-combatant Army units reserved for conscientious objectors and notorious for the treatment of the men in their ranks.

But Mr Walling was not prepared to let his objections lie. Separate military records show he was one of a number of pacifist soldiers who faced court martial for disobedience and were sentenced to death. The sanction was commuted to 10 years’ imprisonment.

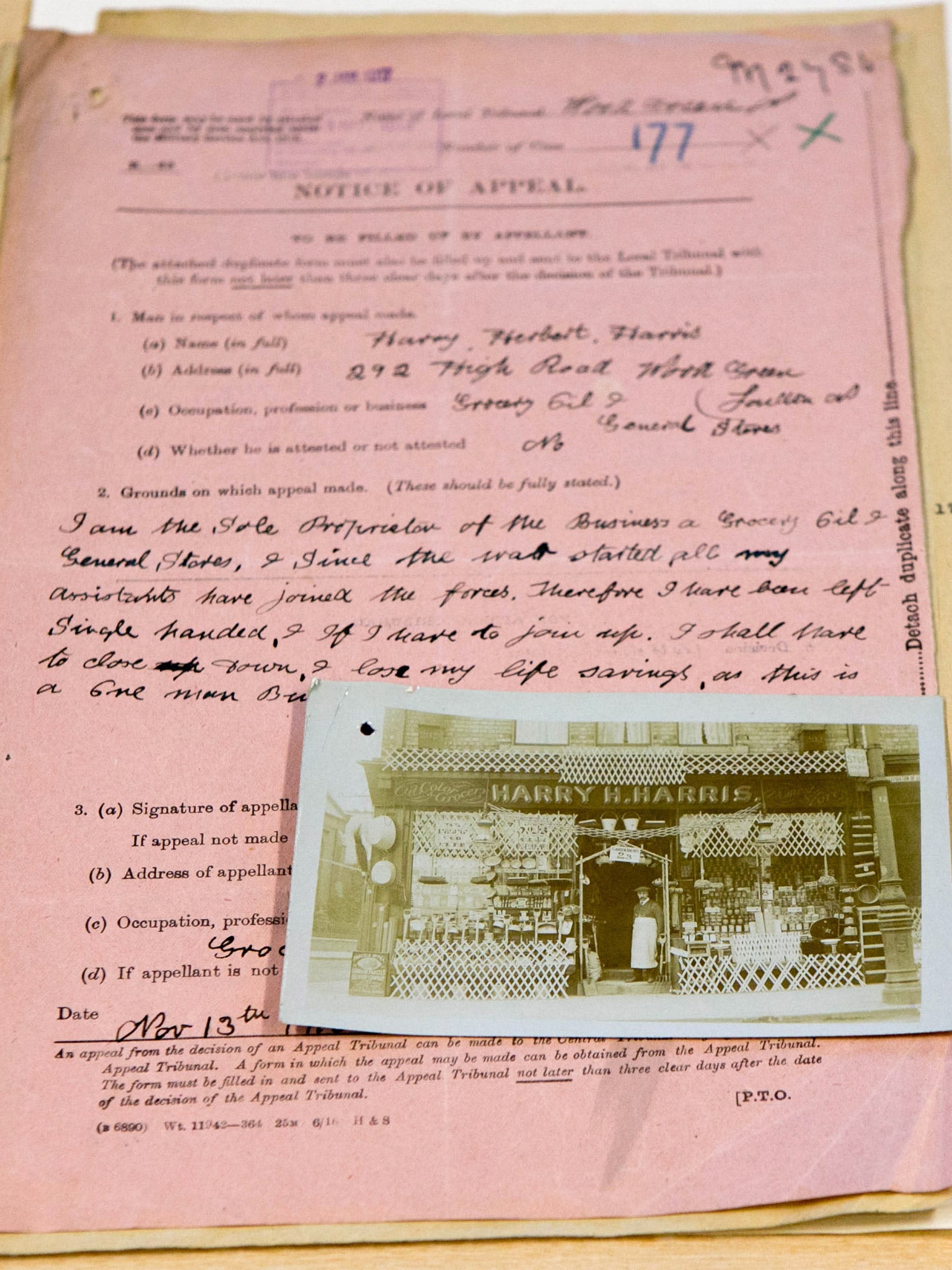

Harry Harris

Pictured outside his north London hardware and grocers shop, Mr Harris was one of many applicants to the tribunal who sought exemption on the grounds that he would lose his business.

To back his application, the 35-year-old from Wood Green submitted the photograph along with a statement that all his assistants had left to fight and no-one was left to run the store.

The tribunal gave him short shrift. He was given a month to put his affairs in order and then report for training.

Other shopkeepers were denounced by neighbours. Charles Bushby, a butcher, was forced to enlist after the tribunal received an anonymous letter saying he had “bragged” how he would never be made to fight because he had joined a volunteer organisation.

His critic described Bushby as “a proper rotter of a man” and a “rotten shirker”. The butcher was made to join up, serving with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force

The wife of Percival Brown

Amid the thousands of pleas to avoid conscription, came one begging for just the opposite fate to be meted out to an apparently feckless husband.

The unnamed wife of one Percival Brown, who had applied in 1916 for exemption on the basis of a back injury, wrote to the tribunal asking for him to be drafted into the Army with all haste.

Mrs Brown, a mother of two, wrote: “I was looking forward to him joining up as I have had nearly 11 years of unhappiness through him.”

Noting that his behaviour “as [sic] caused me to go short of money, food… besides selling part of my house”, she also says her husband had threatened to ensure she “did not get a penny” were he to be sent to fight and ask for him to be forced to pay an allowance.

The documents suggest Mrs Brown got her wish. Her husband’s application was rejected.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments