Queensferry Crossing: The trials and tribulations of constructing Britain's tallest bridge

'Once you’ve finished it you can tell the grandchildren you were on that job, you did that'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

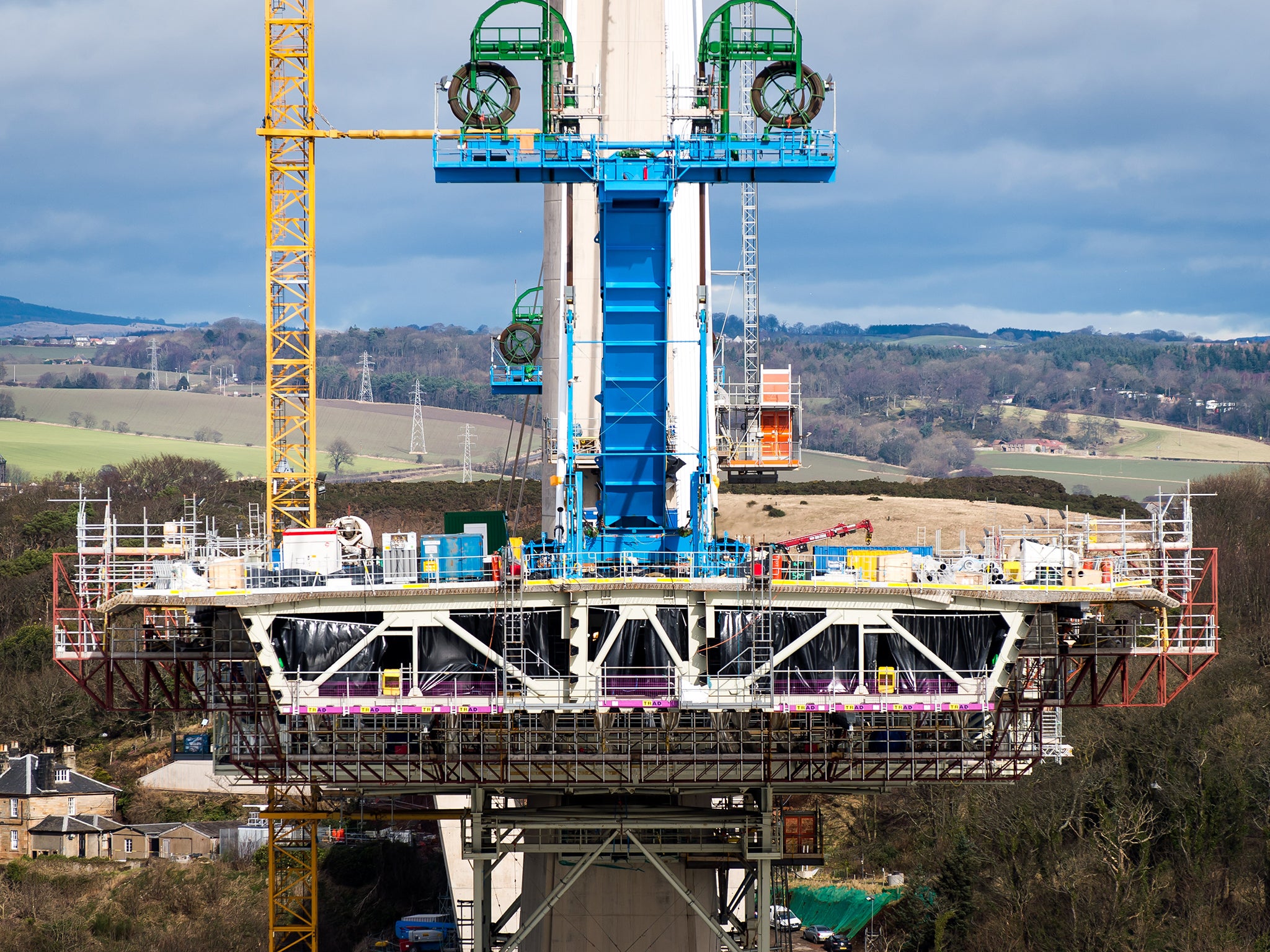

Your support makes all the difference.“I’m used to heights, so it doesn’t bother me one bit,” says Jason Moore. It is just as well. As one of more than 1,200 people involved in constructing Scotland’s new bridge across the Firth of Forth, he and his colleagues regularly work 210 metres above sea level, where they are buffeted by high winds and face weather which can turn extremely nasty in an instant.

Speaking to The Independent during a break in his shift at the top of the Queensferry Crossing’s central tower, the general foreman from Leeds says working under such conditions has made him appreciate the workmanship – and downright bravery – which went into the other two bridges connecting Fife and Edinburgh.

“When you stand up here and look at that, you can’t help but think it was brilliant engineering, back in the day,” he says, gesturing towards the familiar red zigzag of the Forth Bridge, which opened in 1890. “I’ve been over that bridge many times before, but until you get up here you don’t really appreciate how good it is. They’re from three different centuries, these bridges, so I think that’s what makes it a bit nostalgic.”

The Queensferry Crossing is not out to replace Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker’s famous red railway bridge, which has become an iconic symbol of Scotland and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Instead, it will provide an alternative to the Forth Road Bridge, which was only built in 1964 but has recently been making the news for all the wrong reasons.

After a 2cm crack was discovered in a steel truss under the carriageway in December, the bridge was closed to all traffic and only fully reopened two weeks ago. The cost to the Scottish economy is difficult to calculate, but some estimates have put the figure at £50m – which illustrates just how much is riding on its replacement.

Already the UK’s tallest bridge despite still being many months from completion, the 1.7 mile long Queensferry Crossing – which was named through a public vote – is set to cost the Scottish purse £1.3bn. When it opens to general traffic at the end of this year, its poorer cousin will not be dismantled, but instead used purely to serve public transport, cyclists and walkers.

To visit the bridge, which is being built outwards from three towers with foundations dug 20 metres under the sea, you must first leave civilisation behind. The towers are served by “crew boats” which ferry workers clad in orange jackets, helmets and protective glasses across the choppy waters of the Firth of Forth to their shifts. For many, it is quite an expediation merely to get to work.

With supreme irony, the people who were arguably hardest hit by the closure of the Forth Road Bridge in the run up to Christmas were those responsible for building its replacement. Moore, the general foreman, was unfortunate enough to begin his stint on the bridge at the time of maximum disruption and had a nightmare commute from the Scottish capital.

“As soon as that bridge was closed, the impact on people was massive,” he says. “People had three hour round trips, even from Edinburgh.”

In the Marine Office, which plans the movements of staff ferries and the huge pieces of bridge which are taken out to the towers by barge before being lifted into position by specialist cranes, a sign reads: “Rearrange this well known phrase: planning piss prior prevents performance poor.”

While this maxim could apply to any major infrastructure project, it is particularly relevant here, where the weather conditions dictate the construction team's every move. Each new segment of the bridge, of which there are 110, requires a four to five hour window of calm conditions to allow the workers to lift it gently into position – so organisers spend a lot of time poring over weather forecasts.

“You have to take into account the weather more than any other job I’ve come across,” says Iain Cookson, the engineer responsible for managing the work taking place around the bridge’s central tower. “Waves, the tide, the sea state – there’s so many factors here, but that’s what’s fun about it and makes it a challenge. We just have to plan as best we can for when the weather windows are good – you have to take the opportunities when they come or you’ll struggle.”

Being so reliant on the conditions means that Cookson's men often have to change their plans at short notice. When one calm weather window opened late on 28 February, they had to be ready. “Two days ago if you were here you'd be standing on thin air,” says Cookson when The Independent visited 48 hours later, stamping confidently on the newest section of carriageway poking out over the Firth.

The safety statistics for the previous two bridges are not good: 73 three people died constructing the rail bridge and seven on the road bridge. While to an untrained observer the conditions on the new crossing might seem dicey on a good day, the project's organisers insist that the safety of the workers is paramount. Instruments measuring wind are strapped all over the structure and fed into computers, allowing staff to be radioed in to safety if conditions become dangerous.

When the Queensferry Crossing does finally open to traffic, drivers can look forward to a faster and smoother ride. A three metre high shield running all the way along the sides will reduce the effects of the wind, allowing cars to treat it like a motorway: the speed limit will be 70mph, rather than the 50mph currently permitted on the old bridge.

The road surface itself will also be smoother, thanks to expansion joints being placed at either end rather than in each section, allowing for one continuous strip of Tarmac and doing away with the annoying “ba-bump, ba-bump” rhythm that infuriates today's drivers.

Underneath the carriageway, the hollowed-out “deck” section means that much of the internal structure is enclosed and sheltered from the elements, making maintenance much easier. Inside this space, which will also be dehumidified to prevent rusting, a two-man monorail will allow workers to access different bits of the bridge quickly without disturbing the traffic moving above.

David Climie, the project director at Transport Scotland who has overall responsibility for the new bridge, acknowledges that the workers have had to cope with “difficult conditions”, but says the disruption over Christmas “really brought home to everyone” how important a reliable crossing over the Forth was to the national economy.

“Unquestionably, the existing Forth Bridges are icons of cutting edge design and technology for the periods they were built and the Queensferry Crossing will be no different,” he adds. “Having all three together in the dramatic setting of the Firth of Forth makes this, quite simply, a globally unique location.”

Also on shift when The Independent visited the new bridge was Robert Finlay, a senior welder currently working inside the central tower, where he oversees the crucial joining of new bits of the bridge. He and his colleagues are protected by thick curtains at either end of the hollowed-out sections which stop the worst gusts of wind, but life in the “tubs”, as the workers call them, is far from easy.

“I start at 6am and have someone who does a back-to-back with me on the night shift, so we’re basically welding 24/7,” he says. “But it’s a part of Scottish history. Once you’ve finished it you can tell the grandchildren you were on that job, you did that.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments