Britain’s broken justice system revealed as prisoners trapped in jail for five years before trial

Exclusive: Number of accused held on remand hits record high with 15,000 languishing in overcrowded prisons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Prisoners are being forced to wait five years behind bars before trial as the number on remand soars to a record high fuelled by a growing court backlog.

Some 15,523 people were languishing in overcrowded jails without having been convicted as of 30 June – a 50-year high and up 16 per cent compared to the previous year, according to Ministry of Justice figures.

At least 150 people – all male – had spent five years waiting to face a jury, as of 31 December, with Black men making up 33 per cent of those facing the longest waits, data obtained under freedom of information laws by the charity Fair Trials shows.

Close to 2,000 prisoners on remand had been held for over a year. Another nearly 2,500 people were locked up for over six months – after which time a judge must approve an extension.

A top lawyer warned that some defendants were pleading guilty to crimes despite insisting they were innocent because they would be released from prison sooner – as the crown courts cases backlog also reached a new record high, having doubled in four years.

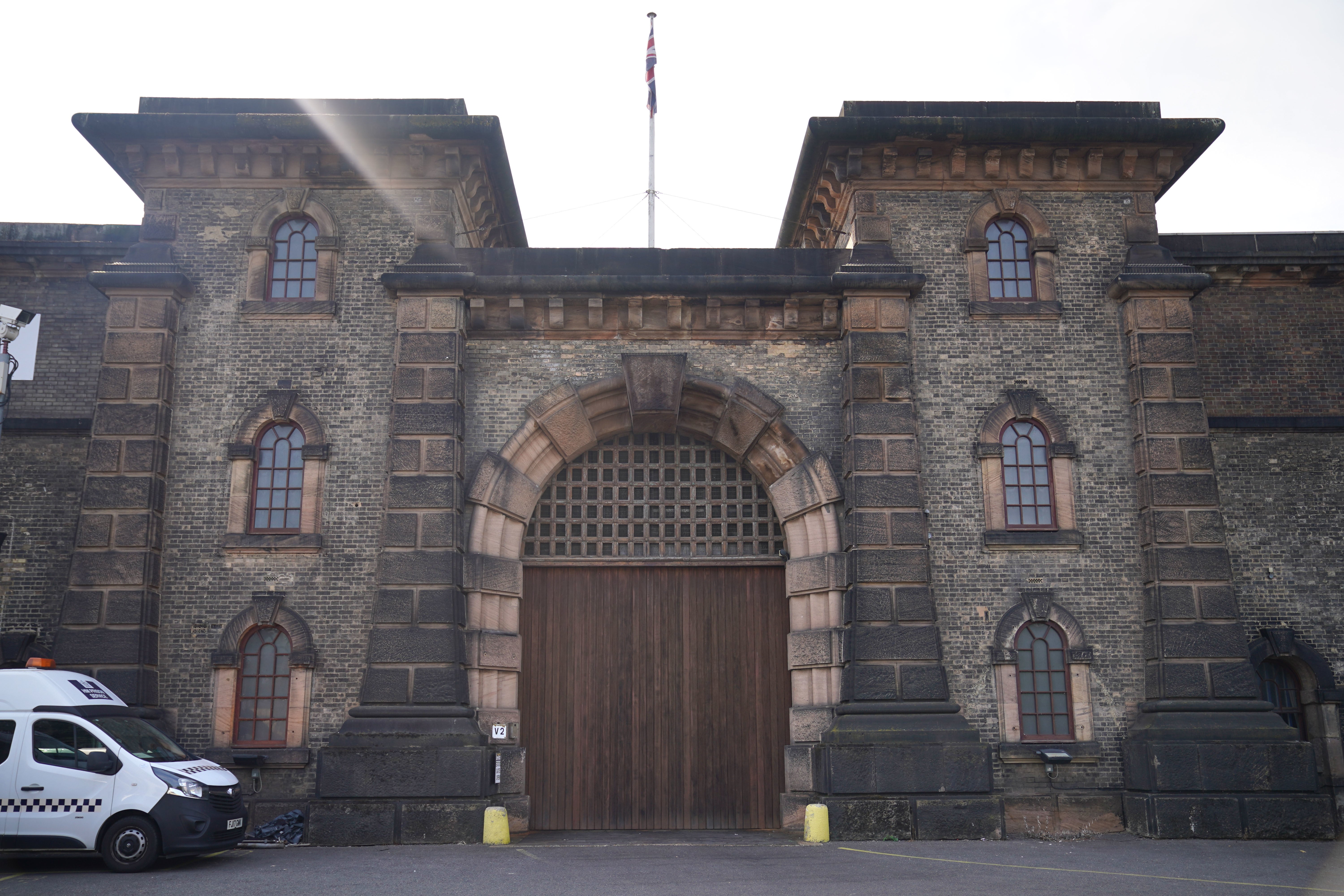

It is the latest shocking indictment on the state of Britain’s justice system as prisons come under the spotlight following the escape of terror suspect Daniel Khalife from HMP Wandsworth last week, amid wider concern over chronic overcrowding and understaffing.

Jack Straw, Labour home secretary between 1997 and 2001, said it was “preposterous” and “just extraordinary” to leave people languishing so long in prison without a trial, accusing the Tory government of “presiding over the most serious crisis in the criminal justice system I can remember”.

Tory MP Robert Buckland, who served as justice secretary for two years until September 2021, called for the cases to be “examined and clearly explained”, warning that “people should not be on remand for years without a proper reason”.

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson said cases involving the longest waits mainly involved complex fraud or were trials with a large number of defendants, that ordinarily take a long time to prosecute.

Lambasting the years-long remand waits as “totally and completely unacceptable”, Blair-era justice secretary Lord Falconer said: “The government needs an emergency plan because we can’t let these long delays continue.”

He called for the greater use of tagging for non-violent suspects and temporary “nightingale courts”, while Mr Straw said ministers “could do a great deal more to bring more courts into operation – including using retired and part-time judges”.

The overcrowding crisis “is most acute” in jails housing prisoners awaiting trial, said Rob Preece, of the Howard League for Penal Reform. He likened lengthy “Kafkaesque” remand times to indefinite prison sentences, which were abolished in 2012 and criticised last month by the UN’s special rapporteur on torture.

As of June, more than a fifth of those held on remand were accused of drug offences, official figures show. Just 32 per cent awaiting trial were remanded for alleged violent crimes, according to the most recent data.

Ian Acheson, the former security chief at HMP Wandsworth, said the under-pressure category B London jail was just one of those struggling to cope with the added pressure of the growing backlog of remand cases.

He said the remand system was “a runaway s***show” and locking up non-violent suspects for five years is “an unacceptable use of state power”. He warned that those on remand “are often at far greater risk of self-harm because of their uncertain status”.

Tory justice committee chair Sir Bob Neill warned that the “churn” of record numbers of remand inmates was putting further strain on prison officers.

It “can only increase the risk of violence” when innocent people are locked in prisons without family visits or rehabilitation schemes, often “in some of the worst conditions”, said Sir Bob.

The situation “has led to a mental health crisis, with levels of suicide and self-harm among remand prisoners skyrocketing as people become hopeless”, said Griff Ferris, Fair Trials’ senior legal and policy officer.

Remand inmates are often among those locked in their cells for 23 hours a day in “harrowing” conditions amounting to solitary confinement, “forced to choose between calls to family and loved ones, exercise or showering, and denied access to education and other rehabilitative programs”, Mr Ferris said.

He criticised the government for “actively contributing” to the remand crisis by “shredding infrastructure and legal aid” and said he believed Labour had “avoided taking any meaningful action” to challenge ministers over fears of being seen as soft on crime.

Claiming that the government “simply cannot get to grips with its basic duties”, shadow justice secretary Shabana Mahmood insisted Labour would “take immediate action” to increase the number of crown prosecutors by at least half, and build prison places pledged but not delivered by the Tories.

“Our prisons are unsafe and unable to provide basic levels of care,” warned Dita Saliuka, whose brother Liridon, 29, died by suicide in HMP Belmarsh on 2 January 2020, weeks after his trial was pushed back six months, having already spent five months waiting.

Ms Saliuka warned that those who see their remand custody limits extended, like her brother, “wait and wait and lose hope”.

Speaking of those eventually acquitted, she added: “You’re in prison for years and then you get found not guilty – what happens after that? You might lose your family, your job, house, employment, relationships. You don’t get any of that back, you don’t get anything at all.”

Conversely, Law Society deputy vice president Richard Atkinson said “there are certainly cases” where defendants will have spent longer on remand than their potential sentence – with some opting to plead guilty to get out sooner, despite lawyers advising otherwise.

“You have to say to clients” that “you are probably looking at six to eight months” before they are tried, to which they may take the “pragmatic” but inadvisable position that “I might as well just plead now … it’s a lose-lose”, Mr Atkinson said.

The court backlog fuelling the crisis also soared to a record high of 64,000 cases in July, figures published this week show – despite a government pledge to slash it to 53,000.

A senior legal source told The Independent that the caseload is instead likely to increase by the same margin, hitting 75,000 in March 2025.

While there were 100,000 sitting days at crown courts last year, the highest level since 2017-18, the legal source said this remains “woefully short” of the 110,000 days recommended by the justice select committee last April – and noted that the backlog is now twice as large as it was back in 2018.

Steve Gillan, general secretary of the Prison Officers Association, said the resulting long remand periods were “totally unacceptable”. He pointed to the government’s decision to close half of all courts in England and Wales between 2010 and 2019, adding: “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

In comments echoed by Sir Bob, Mr Atkinson warned that a push for more police officers and calls for tougher sentences at a time when the courts are in crisis shows “a lack of joined-up thinking” in government.

“If you’re going to shove more into the pipe, you’d better make the pipe a bit bigger,” said the Law Society solicitor. “You need more resources, but we’ve had decades of cuts in court numbers, in investment in remaining court buildings, in legal aid.”

The MoJ said it was working hard to deliver swifter justice through unlimited court sitting days, increased remote hearings, and keeping nightingale courts open.

“Judges make remand decisions independently of government, based on their risk of reoffending or absconding, but this government has done more than any other to tackle discrimination in the criminal justice system, including diverting ethnic minority youngsters away from criminality, to increasing diversity in our world-leading independent judiciary,” the statement added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments