Prison books ban - the view from inside: 'this is taking away our best hope of reform...’

This week, The Independent’s coverage of the Government’s ban on prisoners being sent books attracted responses from current and former inmates. Here they tell Chris Green their views

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

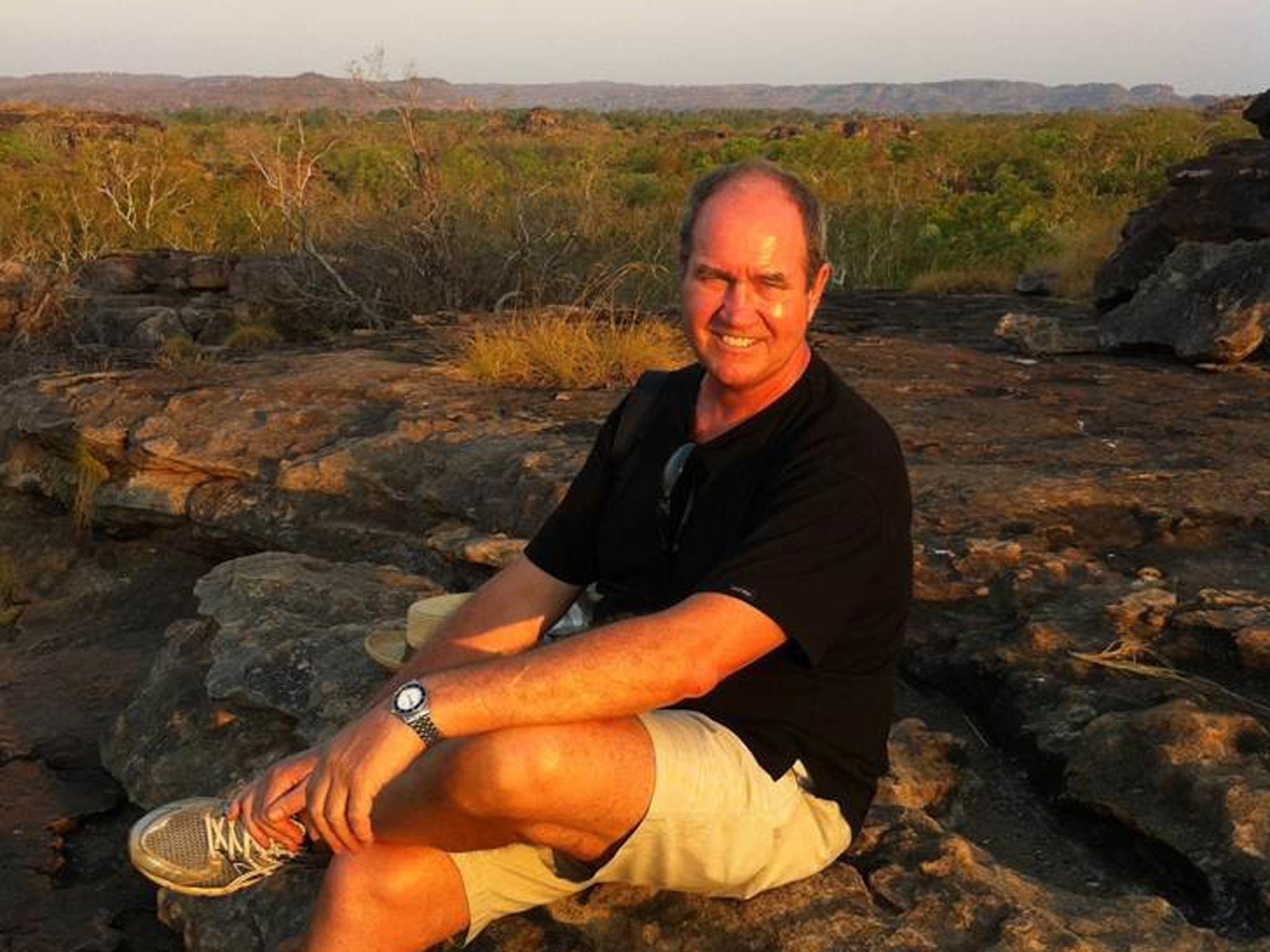

Your support makes all the difference.Thomas Greaves, 67, from Essex, was jailed for 18 months in the 1970s for possession of cannabis resin, but was released after six months on appeal.

“Prison was a devastating experience. It is impossible for anyone who has not experienced incarceration to understand what it’s like to lose freedom. Awaking every day behind bars is sickeningly disturbing and deeply traumatising; the very idea that such an experience might release a reformed character is based upon naivety and plain ignorance.

“Vengeance and punishment play a huge role in the penal system, but to take this to the level of removing books from prisoners is a very dangerous and sadistic move.

“The only real chance a prisoner has of personal development leading to a life of greater responsibility, personal happiness and useful social contribution is education.

“To take away books from a prisoner, their best hope of change and reform, is beyond ignorance: it is spiteful stupidity that benefits no one, potentially harms everyone and destroys trust in the Government to protect society from those whose habitual behaviour is self-defeating and often the result of psycho-emotional unwellness.

“Grayling’s law would have had a very negative effect on my term in prison. While in jail, the University of London gave me a place to study philosophy and, fortunately for me, I was able to ask friends and relatives to purchase the books I needed to read for my first term, which they sent by post.

“The libraries in the two prisons I was locked inside were adequate for general reading purposes, and as far as I know they were used extensively by a significant number of prisoners. My experience was 40 years ago and no doubt much has changed, but I recall having no problems acquiring my books and, fortunately for me, I was encouraged by prison governors to study and given special work-free periods to do so.

“I am completely horrified by Grayling’s law and feel huge sympathy for the prisoners who are being treated in such a callous way.

“It is often said that a society’s treatment of its prisoners provides a measure of its civilisation. If there is any truth in such a notion, it behoves this Government to examine its motives for introducing such a retrogressive law. What kind of justification could possibly be offered for taking away the right of prisoners to read books, educate themselves and develop their imagination through peering into worlds of which they would never dream unless through the works of writers and artists?

“If anyone needs books, prisoners must surely rank close to the top of the list of those who could benefit from them.”

Damian Finch* is in his early 50s. He recently completed a two-year sentence, which he served in four prisons: HMP Bullingdon in Oxfordshire, HMP Moorland in South Yorkshire, and HMP Lincoln and HMP North Sea Camp in Lincolnshire.

“Until two weeks ago, I was a prisoner. In two establishments I worked in prison-education departments, helping other prisoners to learn to read and write, so I feel I have a balanced insider’s view of the current controversy.

“To be fair, this is not a new policy. Long before 1 November 2013, some prisons already prohibited parcels on security grounds. At HMP Moorland, near Doncaster, these rules have been in place since November 2012, so many prisoners might be wondering what all the current fuss is about.

“The real impact is on prisoners who need specialist books (often far too expensive to purchase from weekly wages of £10 to £12) for study or else to maintain or develop new interests or skills.

“Previously, some prisons did permit such books to be sent in from home, or more often purchased by family members via Amazon and sent directly. Now, prisoners have to buy every book they need themselves via the prison system – which uses Amazon – using their wages or the small amounts of private cash families are permitted to send to their prison accounts.

“Also, the new rules restrict the number of books a prisoner can have in their possession at any one time to 12 – excluding the Bible, approved religious texts and a dictionary. For prisoners who do not read much, this isn’t a great hardship, but for those trying to pursue Open University courses or who have other interests where reference books play a key role, it is harsh and frankly punitive.

“While it is true that all prisons have libraries, it should also be said that there are varying degrees of access and quality of stock on the shelves. In many closed prisons, where prison officers have to escort prisoners to and from the library, visits are often limited to 20 minutes or so, once a week. If there are staff shortages or security alarms, then library access is one of the first activities to be cancelled. At HMP Moorland we could go for a month with just one 20-minute session, even though four had been timetabled.

“Prison education used to be a lifeline – and a vital part of reducing reoffending – for many prisoners, particularly those whose early schooling had been curtailed or disrupted. However, recent economic cuts mean that prisons can no longer offer any courses above GCSE as standard. Any more advanced courses now need to be arranged and paid for by the individual prisoner.”

*Damian’s name has been changed for the purposes of this piece

Simon Short, 31, was released from prison three and a half years ago, serving at HMP Manchester, formerly known as Strangeways, among others. He studied for an Open University degree while in jail, funded by the Prisoners’ Education Trust charity, and now runs a social enterprise called Intelligence Project, helping with prisoner rehabilitation.

“Reading and learning and developing was a catalyst for change for me. The Prisoners’ Education Trust funded me, luckily enough, because the prisons estate won’t fund anything other than GCSE level, which is OK for some but inadequate for others. The degree gave me the confidence to go down this career path.

“I think Chris Grayling’s policy is draconian. If you’re in custody you do have access to libraries, but sometimes you have to apply to go there; you’re not just given free access. Sometimes it takes months.

“Libraries are sanctuaries that take you out of the chaotic world of the wing, a real positive space to get lost in knowledge and information. Most of the ones I used were all right, but in some of the prisons it wasn’t really a priority – it was just a token, tick-box exercise because they had a statutory obligation to give you access.

“If there were staff shortages or any disruption in the prison, your access to the library was the first thing that went.

“Access to literature for my degree was dependent on my friends and family buying me books and sending them in. If this new measure had been in place when I was in custody, I wouldn’t have been able to finish my degree with the score I did. The skills and the confidence I got from it have got me where I am now.”

Nicholas Jordan, a current inmate at HMP Oakwood in Staffordshire, wrote the following letter, published in this month’s issue of Inside Time magazine, about his experience of gaining access to books in jail.

“After reading a lot of complaints in your pages about the new system, it struck me that some prisoners are saying they can have only 12 books in their possession – lucky sods! Here at HMP Oakwood we do not have that luxury.

“There is no system in place here to purchase books from an approved supplier. We can buy games consoles or DVD players but cannot get books for love nor money. And nor can we have them sent in.

“The prison library is poorly stocked and trying to order an unstocked title can lead to a three-month wait, though you usually get a slip back saying the title is ‘unavailable’. I find all this ridiculous, especially if you want to use your time to educate yourself. So much for a ‘forward-thinking prison’.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments