How technology is allowing police to predict where and when crime will happen

Report finds that British police have wealth of data but 'lack capability to use it'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Police in the UK are starting to use futuristic technology that allows them to predict where and when crime will happen, and deploy officers to prevent it, research has revealed. “Predictive crime mapping” may sound like the plot of a far-fetched film, but it is already widely in use across the US and Kent Police is leading the technological charge in the UK.

A report on big data’s use in policing published by the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI) said British forces already have access to huge amounts of data but lack the capability to use it.

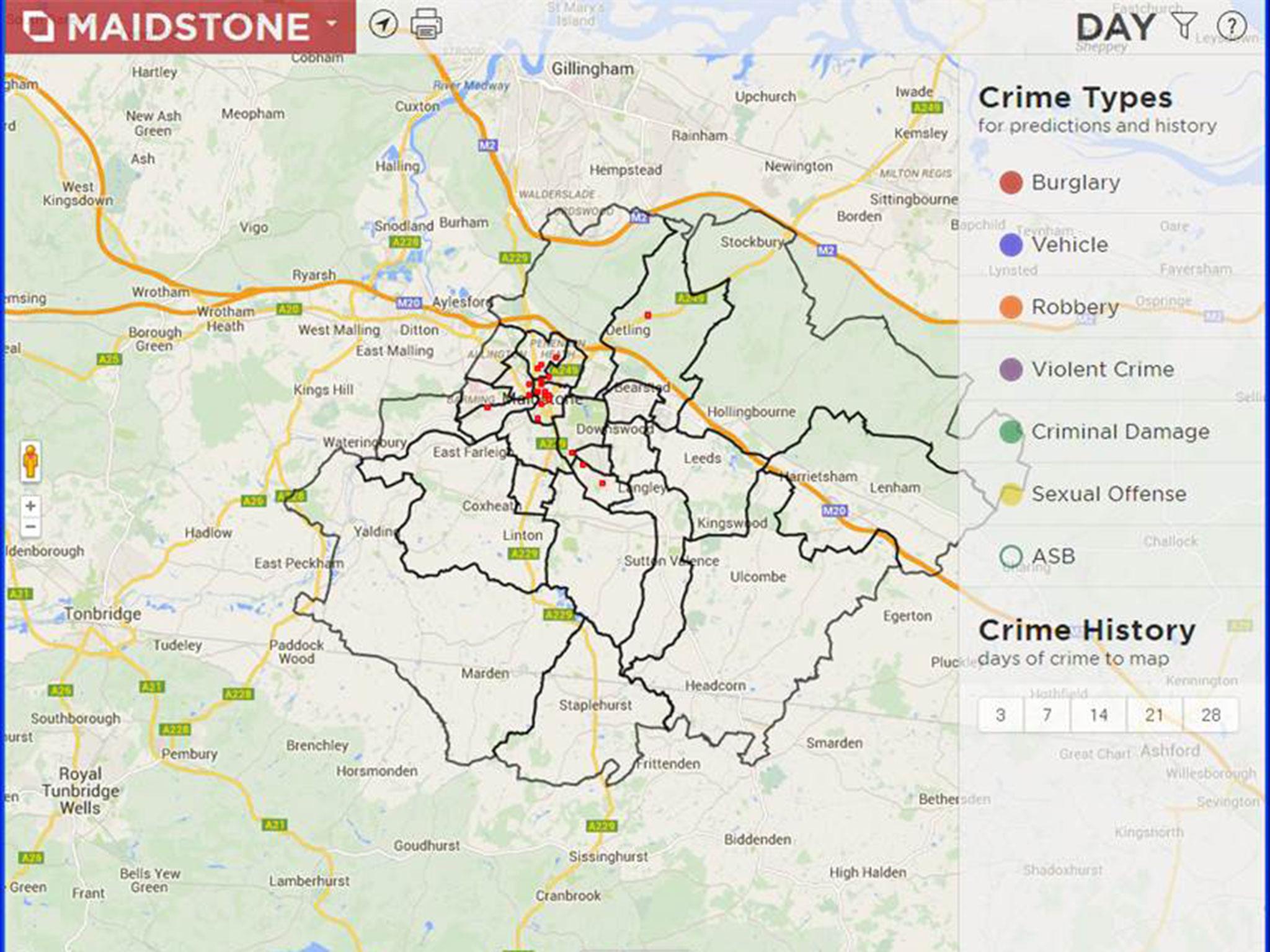

Alexander Babuta, who carried out the research, said predictive crime mapping tools had existed for more than a decade but are only being used by a fraction of British forces. “The software itself is actually quite simple – using crime type, crime location and date and time – and then based on past crime data it generates a hotspot map identifying areas where crime is most likely to happen,” he told The Independent.

“In the UK, forces have found that it’s about 10 times more likely to predict the location of future crime than random beat policing. It allows you to allocate a limited number of resources to where they’re most needed.”

Mr Babuta said the software relies on evidence that crime is “contagious”, frequently being carried out in the same area, by the same offenders, targeting the same people.

Greater Manchester Police developed its own predictive mapping software in 2012 and Kent Police has been using a system called PredPol since 2013.

A spokesperson for the force said the software uses an algorithm originally used to predict earthquakes to estimate the likelihood of a crime occurring in a particular location during a window of time.

“It will pin a series of locations on a map where the highest likelihood of a crime occurring to patrol,” she added. “For every 15 minutes spent in the 500ft square zone it equates to two hours of no crime.”

All officers in Kent can access the system from force computers and print out maps to use on patrol. The reports give the location and main crime types predicted, such as burglary, robbery and sexual offences, and officers are asked to patrol the areas most at risk.

Kent Police said it had received no negative response from staff or the public but PredPol has generated controversy after research showed it appeared to be repeating systematic discrimination against black and ethnic minority offenders. Critics said that by relying on past data to create the software, the program had itself “learned” racism and bias, and would continue reinforcing it even if police forces and wider society progresses. The same allegations have been levelled at another computer program used in American courts to carry out risk assessments for prisoners, Compas.

Durham Constabulary is currently in the process of developing a similar artificial intelligence-based system to evaluate the risk of convicts reoffending. The Harm Assessment Risk Tool (HART) puts information on a person’s past offending history, age, postcode and other background characteristics through algorithms that then classify them as a low, medium or high risk.

RUSI’s report said the system, first tested in 2013, was found to predict low-risk individuals with 98 per cent accuracy and high-risk with 88 per cent accuracy.

But researchers identified vulnerabilities, including the fact that because only Durham Constabulary’s own data was used, offences committed in another area will not show up and dangerous criminals could “slip through the net”.

RUSI also acknowledged the fact that systems like HART that use machine learning will “reproduce the inherent biases present in the data they are provided with” and assess disproportionately targeted ethnic and religious minorities as an increased risk. “Acting on these predictions will then result in those individuals being disproportionately targeted by police action, creating a ‘feedback loop’ by which the predicted outcome simply becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy,” the report warned. “Perhaps partly for this reason, Durham Constabulary’s HART system is intended to function purely as an ‘advisory’ tool, with officers retaining ultimate responsibility for deciding how to act on the predictions."

Mr Babuta said that as well as ethical concerns and a lack of legal frameworks to govern the new technology, a “cultural barrier” had been experienced in some police forces. He added: “Officers rightfully fear that [predictive crime mapping and risk assessments] will replace existing strategies and minimise the role of their professional judgement. All forms of technology can only be used to supplement existing policing ... it’s the role of the police officer acting on the recommendations that is the most important part.”

The researcher said predictive mapping and risk assessments were only a fraction of the ways that technology could improve policing. Sensors currently used for traffic management in cities could be adapted to monitor crowds and prevent riots, Mr Babuta added. “There’s huge amount of digital data that could predict when violence will break out.”

RUSI’s report found that the key limit on the use of emerging technology in policing was data itself, with much crime underreported, making the data unreliable. “In theory there are over 12 million individuals registered on the Police National Computer (PNC), so in theory this kind of analysis could be applied to millions of people,” Mr Babuta said. “But at the moment the data is very much localised and limited to people who have been convicted.”

The researcher said that so far, the “highly localised structure” of British policing had let some race ahead to embrace new technology while others lag far behind the curve.

British police forces use a mix of records PNC, a separate Police National Database (PND), biometric Ident1 database and Europe-wide Schengen Information System.

RUSI’s research found that the “fragmented” databases forced officers to input the same data multiple times, reducing productivity and the will for increased reliance on technology. The UK Digital Strategy was launched in March and lists consolidating databases as a top priority, but limited progress has so far been made.

Mr Babuta said budget cuts to police forces had “undoubtedly hindered technological development” by cutting both investment and the training offered to officers. “The vast majority of police IT budget is being spent supporting legacy systems, many of which are many years out of data, rather than funding new ones,” he added. “There’s now such huge variation across the UK that it will take many years to sort out.”

RUSI’s report was commissioned by John Wright, the head of strategic initiatives at the public sector arm of global technology company Unisys. He first attempted predictive hotspot mapping in 2004, while serving as a borough commander in Derbyshire Constabulary. “I was faced by a huge increase in vehicle crime and burglaries and things like that – we were in a position where volume crime was significant and I was looking for ways where you could prevent it,” Mr Wright told The Independent.

His force used an early form of hotspot mapping that allowed them to allocate patrols and other measures like CCTV cameras and changing road layouts.“The challenge isn’t the technology,” Mr Wright added. “Law enforcement agencies have got rid of a lot of support staff who would have done this data administration and officers are trained largely to rely on their own discretion - they’re very independent.”

Mr Wright said that for emerging technology to work for British forces, analysts needed to put information in a format that offices can use easily and trust. “Restrictions on public finance aren’t going to go away and the rising amount of data that threatens to overwhelm agencies is not going to go away,” he warned. “I think there’s a need to change the culture and exploit that willingness of people using smartphones to help police - the ability to collect that information is so much better.”

Mr Wright noted that many members of the public are already reporting incidents on social media before contacting police on 999, allowing security forces to gather evidence even before they arrive at the scene.

Recent terror attacks in the UK have seen forces appeal for witnesses to send them mobile phone footage and photos that have been used to investigate suspects. Mobile phone apps that can be used to report crime and submit evidence have been rolled out in some countries, but some like the New York-based “Citizen” app – have met with controversy.

RUSI’s report concluded that police forces in the UK have access to a vast amount of digital data but “lack the analytical capability to make effective use of it”. The think tank called for improvements to data systems and the exploration of predictive mapping software to be made a priority.

RUSI called on the Home Office to issue “clear national guidance” to drive the procurement of new technology across the country, as well as better data sharing between individual forces, as well as between the police, councils and other agencies.

The report cautioned that there was an “urgent” need for an ethical framework on how the growing amount of data on individuals should be used without violating privacy.

The College of Policing spokesperson said advances had already changed the nature of policing rapidly over recent years. A spokesperson said any practices and systems shown to reduce crime and increase public satisfaction would be welcomed, adding: “It is likely that greater efficiency and effectiveness could be achieved through better integration and analysis of police data and we have previously provided forces with information to support their use of predictive policing software.”

The Police ICT Company, a private company established by elected police and crime commissioners, said it supported initiatives but faced “obvious logistical challenges”. “The observations and recommendations in the RUSI report are no surprise to those senior police leaders who are already driving information and system- sharing arrangements, and exploring innovations like facial recognition technology and crime hotspot mapping,” said chair Katy Bourne. “We need to ensure that policing is not constrained by legacy technology or limitations in the current ICT marketplace, or by a lack of interoperability.”

The Home Office said work to address the issues identified by RUSI was already underway, with more than £1bn invested in national law enforcement digital programmes. Initiatives include the Emergency Services Mobile Communications Programme, Home Office Biometrics, National Law Enforcement Data Programme and the National ANPR Service.

“As the report highlights, issues resulting from system fragmentation and disparity are by no means insurmountable,” a spokesperson added. “We have protected police budgets since the 2015 Spending Review to ensure forces have the resources they need including making funding for available for reform through the Police Transformation Fund."