Peterloo bicentenary: Manchester massacre remembered as historians draw parallels with politics today

The bloodiest political episode of 19th-century England started the journey to the modern rights we enjoy, as a country, today

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first death came at 1.15pm and was an infant, aged just two years old.

Exactly 200 years ago on Friday, little William Fildes was being carried through a Manchester street by his mother Ann when, from around a corner, a troop of horse-back yeomanry appeared.

The charging cavalry did not slow for the pair. Amid the clatter of hooves and rattling of sabres, the mother was knocked to the ground.

“Her child was thrown from her arms a distance of two or three yards,” an onlooker later noted. “And pitched upon its head.”

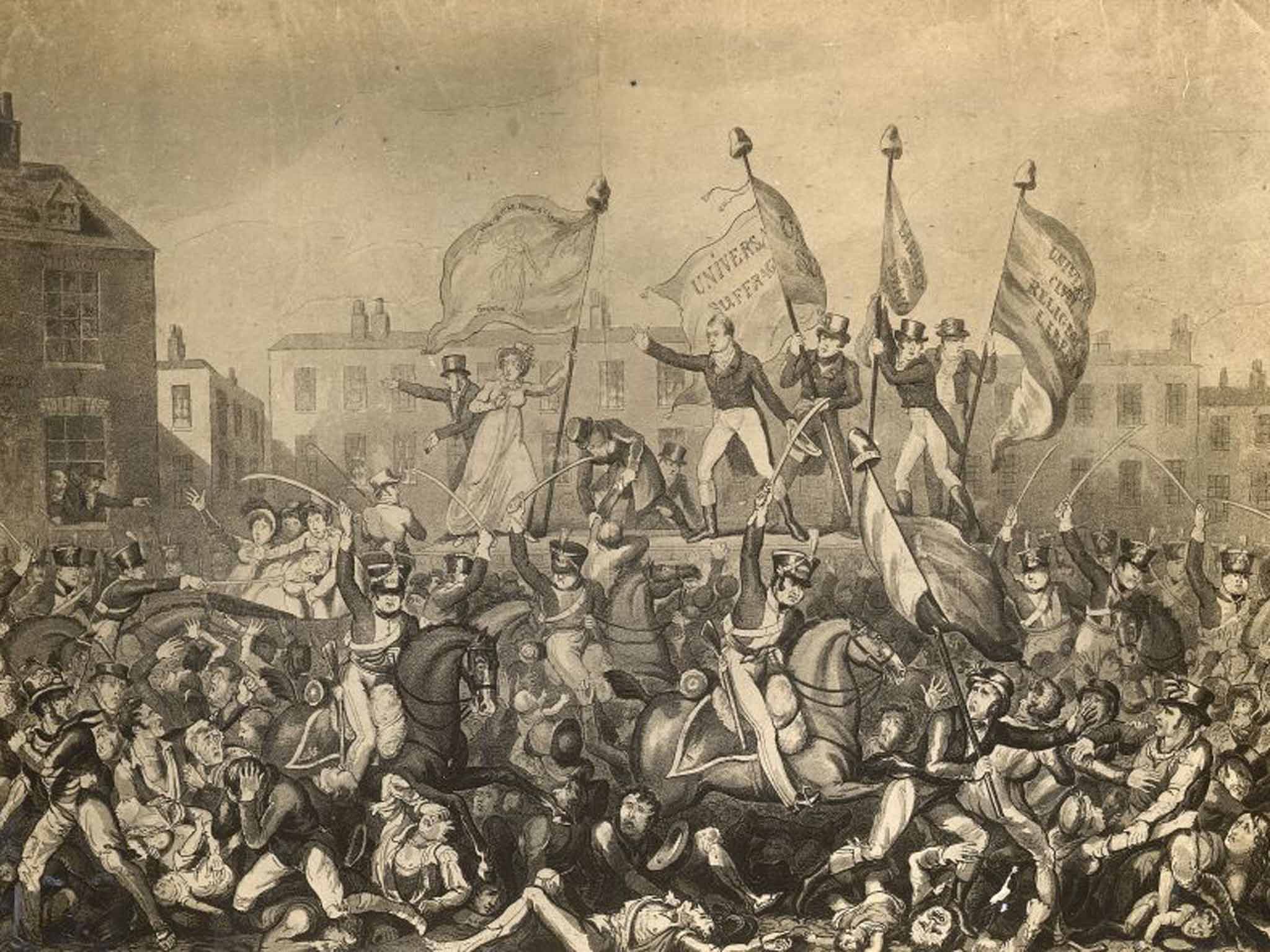

Thus, with the slaying of a toddler, began the bloodiest political episode of 19th-century England: the Peterloo massacre.

By the end of that afternoon, 16 August 1819, some 18 people would be dead, almost 700 more injured and an entire country, it is no exaggeration to say, changed forever.

Men, women and children were all among the slashed and slaughtered as armed forces were sent, at full pelt and with swords drawn, into a packed crowd of entirely peaceful protestors.

They had gone – an estimated 60,000 of them – to cheer orators asking for parliamentary reform and greater suffrage. Many dressed themselves in white as a symbol of peace. Some took picnics. This, organisers said, was to be a show of numbers; not of force or revolutionary intent. But they were met with unforgiving brutality rarely used before in England and never known since.

“Mounds of human being remained where they had fallen, crushed down and smothered,” wrote one attendee Samuel Bamford in the aftermath. “Confusion and terror,” reported the Manchester Chronicle simply.

“What unfolded,” says Professor Robert Poole today, “was so shocking that the consequences of that afternoon continue to reverberate even in 2019. It was the one big event that set the foundation for the democracy we still have.”

The Peterloo massacre has not always been considered of such historical importance. Many 20th-century scholars dismissed it as a localised event only: trouble up north, if you will.

But as the bicentenary is marked on Friday with events across the UK – including an unveiling of the first monument to the massacre in Manchester – many analysts have started to note similarities between then and now: a polarised society, gaping inequalities, heated rhetoric, and a parliament apparently incapable of comprehending, let alone delivering on, the will of the people.

“Certainly, there are political parallels, and lessons we can learn,” says Poole, whose book Peterloo: The English Uprising, is perhaps the definitive text on the event. “What it’s worth saying is that the people in the crowd that day, the radicals and reformers, were supporting a populist movement – and, clearly, they had history on their side. What that shows – and I’m not a Brexiteer – is that populism, left or right, should not automatically be dismissed as ignorant. Popular opinion must be understood and accommodated.”

Yet Peterloo was far more than some vague Brexit parallel.

It was, in fact, says Poole, the beginning of a journey to the modern political rights we enjoy, as a country, today.

“Britain has this history of gradual political reform from 1832 onwards,” he says. “So Peterloo, coming 13 years before that, is often seen to have failed in bringing change. But in fact, this was the great shock that paved the way for everything that followed.”

On that sunny Monday afternoon, an estimated 60,000 people from towns across Lancashire had descended on Manchester’s St Peter’s Field – more or less where the city’s Central Convention Complex stands today – to listen to the famed speaker Henry Hunt.

They came demonstrating because they were hungry and suffering: the infamous Corn Laws had made bread almost unaffordable to large swathes of the population, while the onset of the industrial revolution had simultaneously driven wages down.

But this crowd was not asking for food or better pay. They saw systemic change as the path to betterment. They demanded greater representation in parliament. A few called for that most obscure of dreams in an age where just 400,000 men had the vote: full universal suffrage.

“They were called radicals,” says Dr Janette Martin, archivist at Manchester’s John Rylands Library, which is marking the anniversary with a major exhibition. “But among the number were all sorts of people, many what you would describe as entirely moderate. Workers and Napoleonic War heroes, paupers and patriots, women and children. Hunt [the orator] himself had been a member of the gentry. This was a movement that cut across previous social boundaries.”

Just as pertinently, perhaps, it was a movement that came to St Peter’s Fields in peace.

Such was the expectation of a pleasant day that when the first wave of yeomanry arrived a cheer went up for their bright colours.

“Then,” wrote Bamford of the appearance of these horsemen, “waving their sabres over their heads, and slackening rein, and striking spur into their steeds, they dashed forward and began cutting the people.”

The sheer size of the demonstration had, it seemed, spooked Manchester’s loyalist magistrates. They had ordered the 1,600 yeomanry, special constables and army hussars – all waiting nearby in case of trouble – to disperse the people and arrest Hunt.

The troops followed their orders with something approaching “glee”, says Poole.

“They treated the crowd like you would treat an enemy in the battlefield – right to the point that they seized their banners as you would take an enemy’s flag,” adds the professor.

As terrified protestors fled, exit pinch points became blood baths. The yeomanry – a local, ill-disciplined volunteer force – pursued even those in flight, striking them down, showing no mercy to man nor woman. “A scene of terror, confusion and dismay,” wrote the Leeds Mercury the next day. “No language can do [it] justice; the people were thrown down by hundreds and galloped over, so indiscriminate was the attack and furious.”

It was all over within half an hour; and within days had become known as Peterloo. The nickname – referencing the Battle of Waterloo – was given because those there said it was like being caught in the middle of a war.

Yet if the authorities achieved their hollow victory in the short term – Hunt and other organisers were arrested and jailed – such was the horror of the day that it would ultimately spur the cause of reform.

By 1832, support had grown to such an extent that parliament finally passed the Great Reform Act, which, while a long way from meeting all radical demands, was a first significant step towards a modern democracy. It increased the electorate by almost 50 per cent to 650,000 men and laid the ideological groundwork for a universal suffrage that would finally come, following several incremental steps, by 1928.

Crucially, it looked at one point like the 1832 bill may be rejected by the House of Lords. Protests were organised across England. The country held its breath amid suggestions troops would be sent to disperse such gatherings.

And, then, the Lords backed down.

“Sending in armed troops against unarmed demonstrators after Peterloo was almost unthinkable,” says Poole. “And it has remained that way ever since. Clearly, there have been times, such as Orgreave when the state has deployed excessive force against protestors. But the consensus that using armed force against civilians is not accepted in this county dates back to Peterloo.”

Just last year, while promoting his film about that fateful day, the director Mike Leigh called for schools to teach it as part of their history curriculums, a plea that is now gaining some support.

“It has very much become part of the national consciousness over the last few years,” says Poole. “Now, we must ensure it stays there. It is too important to be forgotten.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments