Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everyone remembers where they were. A startling wake up call on a warm Sunday morning telling us that, while the lights were out, the most famous woman in the world had passed away.

Today we might receive a breaking news alert to our smartphones in the dead of night, wake to discover dozens of unread messages in a WhatsApp group, or check Twitter in case there was indeed something we had missed.

But to reflect on the time when Princess Diana died is to go back to a simpler time, despite being in living memory for most. The avalanche of digital media had yet to come crashing into our lives, burying us under an anxious blanket of constant communication, fear of missing out and an inexplicable desire to reply first to a total stranger’s unsolicited opinion. It was a time when most regular people were contactable only by a landline telephone.

On 31 August 1997, the BBC were still three months away from launching their round-the-clock rolling news service News 24, and BBC World was the only live channel the broadcaster had.

BBC Television Centre in west London was almost completely empty when, at 12.55am, Maxine Mawhinney sat down for another quiet shift as overnight reporter on the channel, with a single producer and director. At 12.58am, just as she was about to deliver the headlines on the hour, a wire flashed up on the office machine: "Diana injured in a car crash in Paris". She remembers the moment well.

“I turned around to my producer and said, ‘That’s quite interesting. Shall we mention that?’ and he said, ‘Yeah if you think you’ve got enough to say’. So the music is running, I do the headlines, and then I said ‘Just before we move on, we’re getting reports from Paris that Diana, Princess of Wales has been injured in a car crash.’ That’s all we had. Then in my ear the producer asked me to just keep going.”

With no mobile phones, no internet access and just one line of copy, Mawhinney then found herself filling time by using an unlikely source of information. “I had been to the hairdressers and I’d read the magazines so I knew all about what Diana had been doing, where she’d been, her summer with Dodi. We kept going, and we didn’t stop.”

BBC presenter Nik Gowing went to bed at 12.30am, only to be woken forty minutes later, and called in to anchor the coverage. He filled the hours by speaking to Maxine, and other correspondents who phoned up to offer their assessments of the situation.

Gowing explains that even in 1997, the spectre of fake news stalked the media. “I overheard in the newsroom, in the background, that a woman had called in and said she’d seen Diana get up and walk away from the scene. As always with these things, you have to think, are we getting the facts here? Getting this right was based on information which was curated and checked as far as possible, but it was damn difficult.”

BBC1 paused their late night gangster film Borsalino at 1.45am to bring viewers a brief report on the accident. In a unsettling coincidence, the film was interrupted during a scene depicting a funeral in France. Still, there was not enough information to clear the schedule, and the film was resumed.

By chance, the Alma tunnel in Paris was near to the headquarters of broadcaster TF1, but mobilising a team in the middle of the night to get to the location and set up a playback facility was not a task that could be performed quickly. When footage of the crash finally emerged after about three hours, Mawhinney realised that reports Diana was suffering merely "a concussion, a broken arm and cuts to one of her thighs" were probably understated.

“When the first pictures came through I looked up and thought ‘Oh my goodness. How has anyone survived this?’ We already knew that Dodi was dead, but when we saw the car we knew it was awful.”

As the hours went by, broadcasters from around the world were calling to ask if they could opt into the BBC stream, bringing the audience up to an estimated half a billion people, and putting the heat on the tiny London operation. The 2002 film The Queen depicts the senior members of the royal family watching Gowing and Mawhinney’s coverage as they awaited news at Balmoral.

While much of the assembled BBC team didn’t yet have much experience in carrying hours of live, rolling news, Sky News had been doing just that since 1989. Kay Burley, one of their most reliable anchors, was woken at 3am.

“I got a call saying Dodi was dead, Diana was fine, but they thought she’d probably broken her leg,” she recalls. Using only the wires that were coming through mainly from French services, the Sky team tried to piece together a picture of what was going on.

“One wire had suggested that the plane of the Foreign Secretary Robin Cook was being held on the ground at Manila Airport, and there is a protocol that no member of the British Government can be in the air when there’s an announcement of a royal death. So that was our first indication, but we were told to stay clear of saying it because of the magnitude of what it could mean.”

BBC correspondent Nicholas Witchell, who was travelling with Robin Cook, called London to reveal that Diana had in fact died, at around 4am. But without official confirmation from Buckingham Palace, it couldn’t yet be reported. Mawhinney recalls the moment the historic news dropped.

“It was one of those moments you never, ever forget. I was still broadcasting when I heard it in my ear, ‘She’s dead’, and I could feel goose bumps on my arm. It was a newsroom of hardened hacks that went completely quiet. At that point we needed to change the tone of the broadcast, we needed to bring it down, so that the expectation of the audience was lowered slightly, but without saying that she was dead.”

For the best part of an hour, Gowing kept conversation going with Stephen Jessel, a correspondent on the phone from his Paris apartment. Both of them knew Diana was dead, and tried to prepare the audience for the worst, while they awaited the green light. Friends of Gowing’s who were watching in the Caribbean later told him, ‘We knew she was gone when you knew’.

Finally, with the authorisation of a senior executive, at 4.41am, Gowing cited the Press Association who claimed that Diana was dead, and at 5.20am official confirmation came from Buckingham Palace.

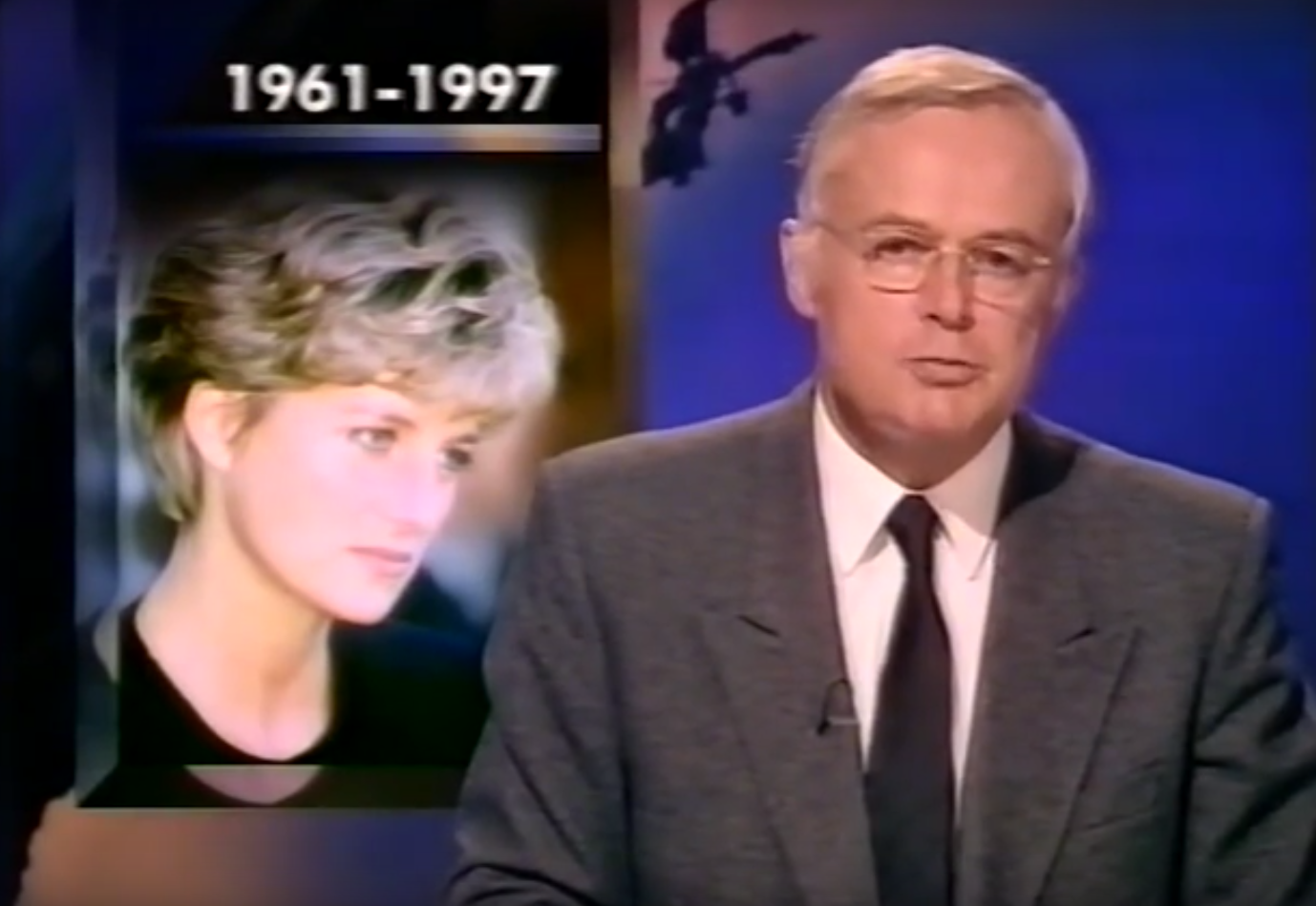

By the time most of Britain was waking up, Martyn Lewis was anchoring a special programme on BBC1, which informed most people of the tragedy for the first time. Wall-to-wall coverage continued, and the overwhelming public response reaffirmed just how big a news story this was.

Twenty years on, it’s curious to consider how differently things might have panned out had Diana's death happened in the present, in our social media-obsessed world; the unsavoury Snapchats and Facebook Lives from the scene, not to mention the inevitable tweets from the White House.

Princess Diana’s death was a story that came on the eve of a digital revolution that would transform the media, and the world as we know it. Then, less than 10 per cent of the UK population used the internet at home, compared with 90 per cent in 2017. Then, traditional media was king, whereas today any information that is available can be accessed almost instantly. But in 1997, what we’ve come to know as citizen journalism was still a long way off – something Nik Gowing says he’s grateful for.

“There were a lot of people hanging about there,” he says of the Alma tunnel that night. “If you can imagine what would have happened if people had started turning up with their iPhones and started filming this stuff. There would have been something uploaded within minutes which would have been dreadful, and we were saved that really. I think the non-ability of social media that evening means we didn’t have to make some very difficult editorial decisions.”

It is a remarkable sign of the analogue times that none of the fabled photographs taken by the paparazzi in that devastating moment ever saw the light of day. It is inconceivable that any such content could be completely eliminated in today’s world – though getting that extra paparazzi shot of the Princess may not have been a matter of life and death in the era of constant Instagramming.

“The advancement of social media means that news of her death would have undoubtedly been in the public domain earlier,” Kay Burley accepts. Even before social media, she says digital advancements made a “huge difference” to how Sky were able to cover 9/11 just four years later, when live footage began beaming around the world within minutes.

But, she doesn’t feel today’s resources would have changed the Diana coverage all that much. “There was no way there could have been any more blanket coverage, and the shock the nation suffered could not have been any more profound.”

Matthew Shaw is a senior BBC editor who was a junior producer in 1997, who came in to help out that morning, sending teams to Paris, Althorp, Sandringham and anywhere else with a link to Diana. He’s not convinced social media would have changed the coverage much either.

“If this happened today, I think we’d probably need more reporters because we have more services to respond to – UK news, world news, online, Facebook – but I think ultimately the coverage would look pretty much exactly the same.”

When other vaguely comparable tragedies happen today – whether it’s the death of a celebrity, or a horrific terror attack – people are used to taking to social media to react. Hashtags are employed and profile pictures are changed as marks of respect, and a tide of grief spreads quickly, which people feel they need to join.

In a pre-social media world, this is the kind of behaviour which was essentially played out in real life – with hordes of people descending upon various royal palaces and homes, leaving flowers, writing tributes, hugging strangers, and pouring their hearts out to TV cameras in a way that had never been seen before. Matthew believes the early TV coverage was something of a catalyst for this.

“With TV early that morning, you were seeing what was happening, and people felt compelled to go and do the same thing. That’s what we do as human beings, we see things and we want to take part in them.”

Today, our media has changed irreversibly. We learn news instantly, and get to see it raw, live and unedited – for better or for worse. And yet for all the digital and technological resources at our fingertips, the thoughts we share on social media have only become more personal, more open – and when the occasion calls for it – more emotional. Performing grief publicly is something we’ve become accustomed to doing; and it traces right back to learning the news about Diana.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments