Miscarriage of justice review body told to be ‘less cautious’ in hard-hitting report

MPs to say the Criminal Cases Review Commission should not fear disagreeing with the Court of Appeal in its referral decisions. But its chair says it is underfunded and overworked

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Innocent victims of miscarriages of justice are “languishing in jail” due to delays and faults in the case review system, according to MPs behind a hard-hitting report to be published this week.

The Birmingham-based Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) will be criticised for failing to explain its work to the public and for excessive variation in the approach and expertise of its case managers. The CCRC will be told that it should not be fearful of being rebuked by appeal court judges when seeking to overturn wrongful convictions.

The CCRC was set up in 1997, following an inquiry into a series of high-profile miscarriages of justice involving the Birmingham Six and the Guildford Four. It was the first body of its kind in the world. MPs heard evidence that despite Parliament’s intention for the CCRC to be robustly independent of the legal system so that it could properly assess whether mistakes had been made, too often it proved “deferential and subservient” to the Court of Appeal. As a result it had become too “timid” in bringing injustice cases forward leaving innocent people to serve years behind bars.

According to a source on the influential Justice Select Committee, MPs are concerned that the CCRC has become timid and fearful of criticism from judges. Some critics accused it of becoming the Court of Appeal’s “lap dog”. The report will criticise the test that the CCRC uses to judge whether an injustice case will be pursued. The test is for whether there is a “real possibility” of a conviction being overturned.

Last year, Supreme Court Judge Lord Thomas called on the CCRC to no longer limit its inquiries to these types of cases, pointing out it was the “safety net” should there be any possibility a wrongful conviction had been made. Professor Jacqueline Hodgson, from the University of Warwick Law School, has suggested adding a “lurking doubt” test criterion.

“Our concern is the reasonable prospect [ie real possibility] test” said one Justice Committee source. “The CCRC is applying this test too tightly – it’s the wrong test. It needs to look at whether something has gone wrong, whether there is something wrong with the evidence. It’s acting like another court.”

The report is also expected to express concern over the skills of case workers. “The way in which cases are handled seems to vary immensely,” a source said. “The CCRC needs to be better trained and better resourced.”

MPs will also criticise the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) for cutting CCRC’s funding, which they believe is financially counterproductive as it will heavily delay cases from being processed. The commission’s budget has been slashed from £8.1m a decade ago to £5.1m today. The organisation had expereinced a 60 per cent increase in review applications during the same period.

Richard Foster, the chair of the CCRC, told MPs a lack of finance was the biggest inhibitor of the commission’s workload.

Mr Foster argued that for every £10 the CCRC spent 10 years ago, it had only £4 today. He said he was “quite certain” this was the biggest cut anywhere in the criminal justice system, but claimed that he only needed £1m from the MoJ to clear the backlog.

“£1m is 0.1 per cent of the Ministry of Justice’s £9bn budget, so it is a very small percentage. It is the same amount as one Tomahawk missile. I don’t know how many Tomahawk missiles the Royal Navy has, but if they could manage with one fewer, we could clear our queues.”

The CCRC insists only 1.2 per cent of Crown Court convictions result in requests for case reviews. Criminal appeal lawyers dismiss CCRC claims that this shows 98.8 per cent of convictions are safe, and argue that it is only the tip of a much bigger iceberg.

The MPs will challenge the MoJ to find that £1m. “This is a very pressing matter – it either means that people are left languishing in prison or those who have been released still might have an unfair conviction hanging over them,” said an MP.

The average waiting time for assessments on cases referred to the CCRC is six to 18 months.

The CCRC denied to MPs that they “lacked courage or forthrightness or did not dig deep enough”.

Mr Foster said: “We have an idealistic belief in our independence but that does not blind us to the legal hurdles we have to overcome. They were not set by us.”

* This article has been amended. It originally ascribed the description of the CCRC as a Court of Appeal ‘lapdog’ to the select committee report. In fact, that term was used by a critic of the organisation in evidence to the committee. The CCRC was not criticised for ‘failing to investigate cases adequately’ as originally stated; rather it was criticised for the excessive variation in expertise between case managers. The test applied by the CCRC is the ‘real possibility’ test, not the ‘reasonable prospect’ test, as we originally said. 27/3/15

‘Dad never stopped trying to clear his name’

“We all knew Dad didn’t do it but what happened to him broke up our family anyway. My mum was left singlehandedly to bring up the four of us,” Steve Stock says.

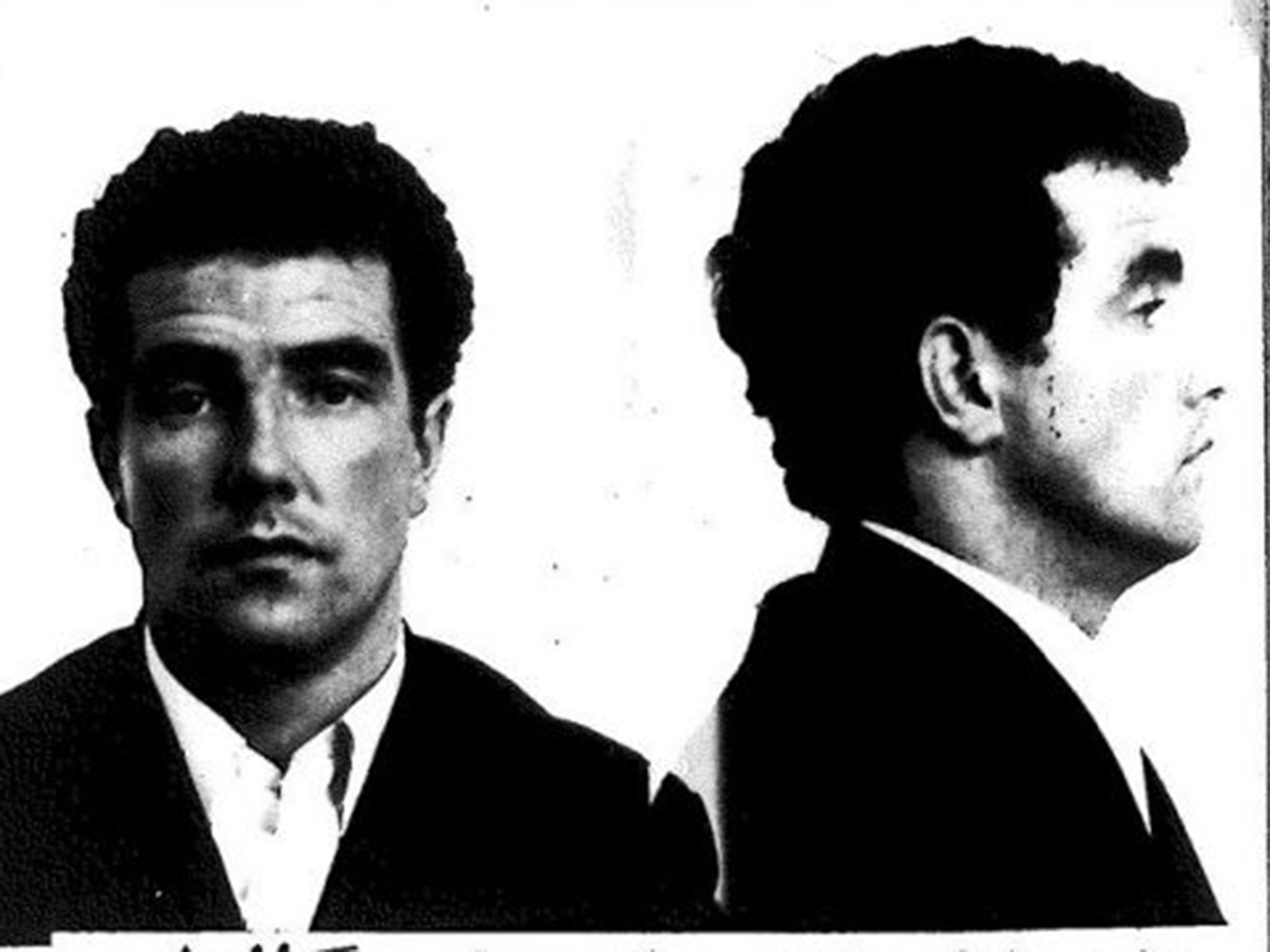

At 6.47pm on Saturday, 24 January 1970 a gang of robbers attacked supermarket staff as they took the weekly takings a short distance from Tesco’s to the night safe at Lloyds bank around the corner in the Merrion shopping centre, Leeds.

The store’s manager and his colleague were bludgeoned around the head with iron coshes, £4,000 was snatched (enough to buy a house in 1970) and the robbers fled in a waiting getaway car. The police claimed Tony Stock was one of them.

He always insisted the police lied. He said he was at his house in Stockton-on-Tees, celebrating his 30th birthday with his wife, Brenda and their four kids: Steve, who was just two years old; his two big sisters, Antoinette (“Twinnie”), five, Charlene, nine; and baby Anthony.

Twinnie, Steve and Anthony still live around the corner from the house they grew up in. To this day, Twinnie recalls the party. When I asked how she felt about the book I was writing on her father’s case, she told me thought it was a great idea. She said that she really wanted to know that he didn’t do it.

“But you know your dad didn’t do it. You were there,” I pointed out.

“Even though I have memories of the day – singing happy birthday and celebrating – I was only five years old. It is a blurred memory,” she says.

“People are cruel. Even though you tell them he didn’t do it. You would hear the cynical remarks: ‘They all say that.’ It begins to chip away at you.

“It’s years of people disbelieving you that wears you down. My father must have been a very strong character to continue his fight till he died.”

“From day one, Tony was fighting the system and he never gave up,” recalls Tony’s older brother Alan, who visited him in prison every other week. He says Tony’s imprisonment destroyed an entire family. In particular, he remembers the devastating impact of a 93-day hunger strike in Gartree prison.

“He lost so much weight he had to be fitted with a calliper to support one of his legs,” Alan says. “He only called the strike off because he overheard prison wardens threatening to move him to the Isle of Wight which meant we couldn’t see him. It didn’t just wreck Tony’s health, but the health of our mother, who couldn’t cope.” Mary Stock was heartbroken by what had happened to her second youngest child. She died of cancer soon after Tony Stock was released in 1976.

“I didn’t really know my dad when I was growing up,” Steve says. “Life was hard for us growing up. Even now just the other day somebody came up to me and said: ‘You’re the bank robber’s son, I remember you.’ ”

“My mum was left to look after us all,” Steve continues, “but life didn’t move on for Dad. He never stopped trying to clear his name. And why should he? He was innocent.”

“It’s now over two years since our Dad died,” Anthony adds. “We feel we can’t scatter his ashes till he has justice. He spent 43 years of his life trying to clear his name. As a family, we’re committed to carrying on his fight along with Uncle Alan. We know he didn’t commit this crime he was imprisoned for.

“Anyone who takes a proper look at this case knows Dad didn’t do it.”

Jon Robins

The First Miscarriage of Justice: The ‘Unreported and Amazing’ Case of Tony Stock, by Jon Robins, published by Waterside Press

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments