Mina Smallman: ‘What happened to my daughters could happen again’

The murders of Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman were a tragedy, but it is the actions of the two police officers who took photos of their dying bodies that their mother can never forgive. She tells Joe Shute that, were it not for the secret trauma in her own childhood, she doesn’t know if she would have survived...

Family celebrations for Mina Smallman come burdened with unimaginable pain. Over the Christmas holidays, she is unable even to be at home, for the reminder of the voices and laughter that once filled the house.

Above all, however, it is the birthday of her eldest daughter, Bibaa, that she feels most acutely. It marks the moment when, in June 2020 after a Friday night picnic in a park to celebrate Bibaa’s 46th birthday, Bibaa and her 27-year-old sister Nicole (known as Nikki) were stabbed to death in a frenzied attack.

A cherry tree is planted in their memory at Fryent Country Park in Wembley, where 18-year-old Danyal Hussein murdered them in the belief that he needed to “sacrifice” six women every six months. But understandably, Mina finds it too painful to visit.

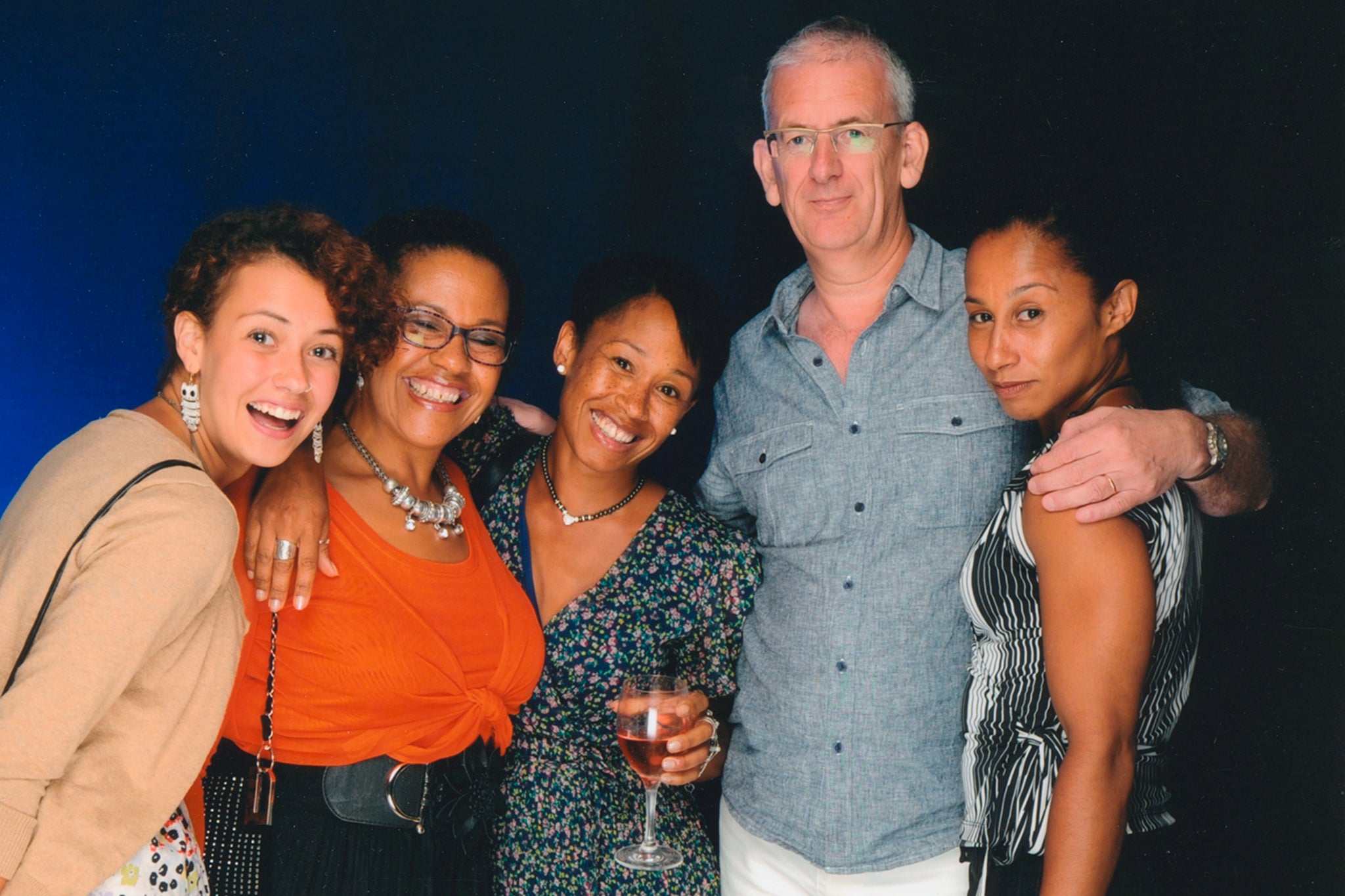

Instead, she prefers to remember her daughters at another cherry tree planted in their memory in the grounds of Canterbury Cathedral. Last month on Bibaa’s birthday, she and her husband of more than 30 years, Chris, drove there together for a day of quiet reflection.

But even then, Mina still took the time to arrange a conversation with the Dean of Canterbury to discuss designating an area of the cathedral grounds as a safe space for female survivors of trauma and abuse. A few weeks prior to that, she spoke at a vigil for the murdered lawyer Zara Aleena, standing alongside Aleena’s family and the parents of Sarah Everard (the 33-year-old who was abducted, raped and killed by Metropolitan Police officer Wayne Couzens).

This is the public face of Mina Smallman, whose own devastating loss has compelled her to campaign against violence directed at women and girls, which this week has been declared a “national emergency” in a new report by the National Police Chiefs’ Council. But she has also dedicated her time to battling what she describes as a deep-rooted misogyny and racism within the police service itself.

When the police were initially informed that Bibaa, a social worker, and Nikki, an aspiring photographer and Westminster University graduate, had failed to return home, such was the inertia that they didn’t even properly launch a missing persons inquiry.

It was Nikki’s boyfriend of eight years, Adam, who was left to discover their bodies hidden in undergrowth in the park. Worse was to come. Two Metropolitan Police officers entrusted to guard the bodies instead took photographs and posted them to public Whatsapp groups, describing them as “dead birds”.

Today, Mina calls Deniz Jaffer and Jamie Lewis (who were both sentenced in 2021 to two years and nine months in jail) “Despicable One and Despicable Two”. She has publicly acknowledged that she has forgiven the killer, although she says she cannot bring herself to do the same for the officers.

They were released on licence early after serving only 17 months. Rather than being warned by the Met, Mina tells me, she found out via a journalist after returning from a holiday.

“I just didn’t want to be here,” she says, describing the moment when she heard. Ultimately, she says, the actions of the officers, and the subsequent handling of the case, exacerbated her trauma to such an extent that it drove her towards a suicide attempt, something she details in her new book A Better Tomorrow: Life Lessons in Hope and Strength.

We are talking in a quiet corner of a hotel in Ramsgate, not far from Mina’s home overlooking the Kent harbour. That was where I first met her back in 2021, for her first full newspaper interview following the trials of the murderer of her daughters and the police officers who violated their bodies. Since then, she understandably prefers to keep her house as a private “sanctuary”.

While acknowledging the good work of some within the police – including the family liaison officer who supported her, and a colleague who painstakingly combed rubbish dumps, gathering the crucial DNA evidence that led to the murderer’s conviction – Mina is unsparing in her book.

Particular fury is reserved for the former Met Police commissioner Cressida Dick, who consistently failed to acknowledge the widespread culture within the force. Mina was visited by Dick at her home. Then, following an investigation by the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), Mina received an official apology from the force, which only served to fuel her anger. “She was just doing something to look as though she cared,” Mina says.

Last year, Louise Casey, a crossbench peer in the House of Lords, published a report following an investigation of the toxic culture within Britain’s biggest police force, which found it to be institutionally racist, sexist, misogynistic and homophobic. Does she think this remains the case?

“Oh yes,” she says without hesitation. “It’s about an acceptance that not everybody at the institution is racist, but the systems that are in place are racist.” She speaks of encountering an ingrained “arrogance” within the police, a sense that “we are in charge and this is how we do things”.

A report published in March reveals that, since the murder of Bibaa and Nikki, 119 police officers across the country have been convicted of crimes including rape, sexual assault and other sex offences (a figure believed to be an underestimate). Could what happened to her daughters at the hands of the police happen again? “I think they would be very wary now, in the Met, because of this scandal,” she says. “But I think it could easily happen somewhere else in the country.”

She has a better relationship with Dick’s successor Mark Rowley. She tells me he came for dinner a few weeks ago, and, unlike Dick, has personally apologised for her treatment. Even so, he continues to reject the Casey Review’s findings of “institutional” racism. “I like Mark. He is a nice guy but he is the wrong guy to do this job,” Mina says. “It takes someone to go in and blitz it to change something.”

When we first met, Mina – a passionate believer in restorative justice – was open to meeting the officers who had photographed her daughters. As she details in the book, however, both subsequently appealed against their sentences, and she withdrew her request, feeling that they would use it as leverage.

“I would do it [meet them] now if they asked to, because there is nothing they would gain from it other than to face the mother of the girls,” she says. “But I know they won’t. If they had a heart in the first place, they would never have done what they did.”

She has no interest in meeting the murderer of her daughters, who taunted her and her husband throughout the trial and is now in prison, where he will serve a minimum of 35 years. “It would be a waste. I never think about him. It is like he never exists,” she says.

Mina’s tough exterior, she admits, is an armour honed in part by her teaching career in various London schools – and her time in the Church of England. She was ordained a deacon in 2006 – the Church of England’s first female archdeacon from a Black or ethnic minority background – and encountered many of the same institutional failings she recognises within the police. “Racist, classist, misogynistic – you name it,” she says. She stepped down from her final post as Archdeacon of Southend in 2016.

But something Mina has never spoken about publicly, until now, is how she learnt to shield her emotions far earlier, during a deeply troubled and traumatic childhood.

Mina was born to a black Nigerian father, who was studying in Manchester for a medicine degree, and a white mother, who, having grown up in a mining family in Scotland, had moved south and was working in a factory. A strong streak of clinical depression runs through Mina’s Scottish side, and her mother’s mother, grandmother and aunt all died by suicide.

By the time Mina was born, they had moved to what she describes as a “dingy two-bedroom fleapit” on the middle floor of a Victorian house in Cricklewood, London. Mina nearly died twice in the flat, once of pneumonia and once because of a gas leak. When she was nine months old, her parents moved her (privately, she believes, without social services being involved) into a foster care placement in Essex.

Mina recalls this as a happy time, but at the age of five she returned to live with her parents. Throughout her childhood, she recalls how her mother would violently beat and coerce her and her older sister, Anne, while her father was also a strict disciplinarian. With money tight, she says, her mother supplemented her meagre income with sex work.

Mina writes in the book about living in constant “dirt and chaos”. “When you grow up in an environment like mine,” she tells me bluntly, “you either survive or you don’t.”

While still a schoolgirl, and partly in an effort to escape her family, Mina started a relationship with a boy who was several years older, called Herman Henry (now a retired boxer). She left school before completing her A-levels, and the couple married and had two children together while Mina was still in her teens: Bibaa, and her sister Monique (who now lives in the Netherlands).

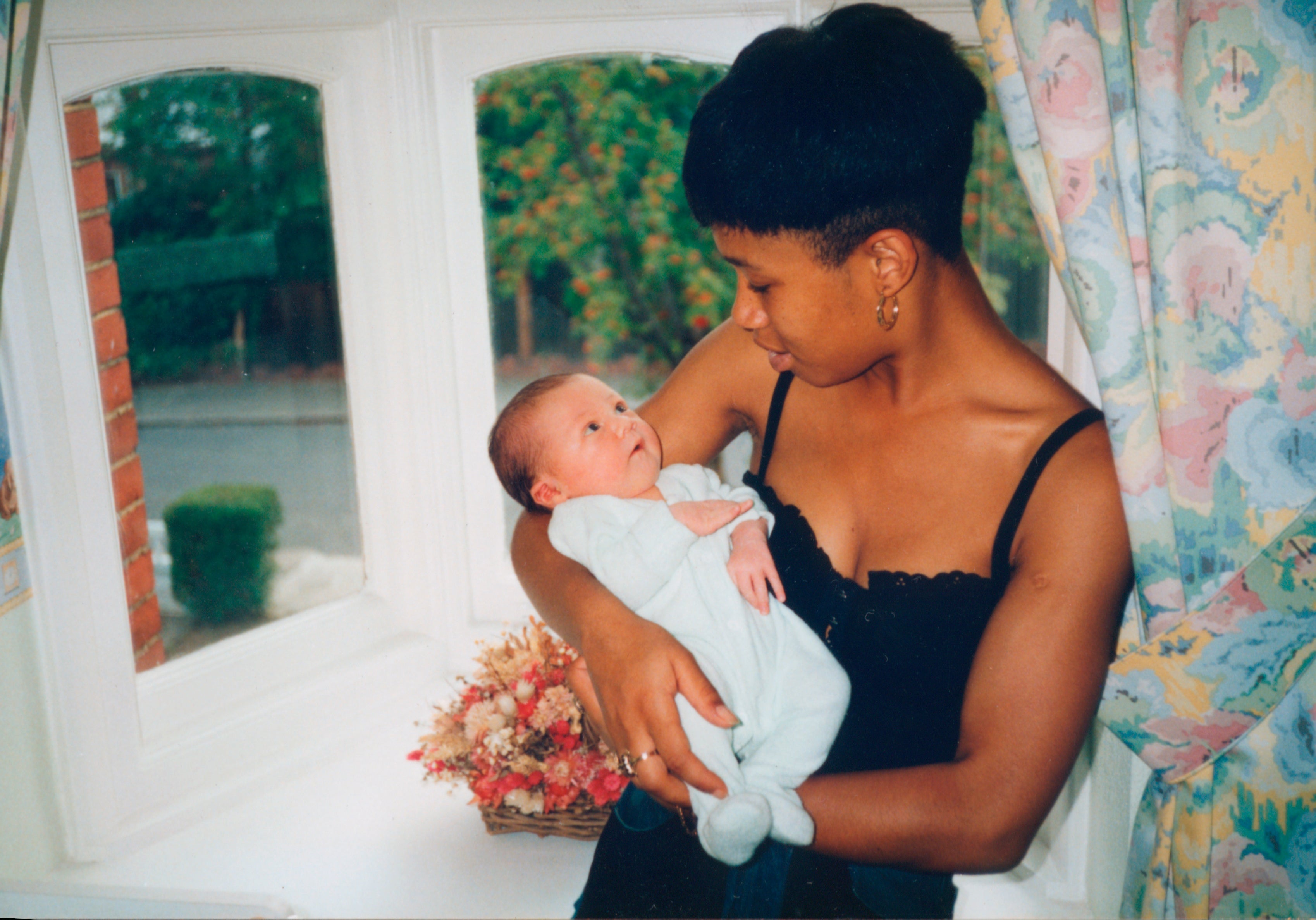

However, their relationship was deeply unhappy, and Mina left in her twenties. She met Chris in 1988 after taking a job as a drama teacher at a school where he taught English, and the couple had another child, whom they named Nicole.

Mina created the kind of secure home life for her daughters that had been cruelly absent in her own upbringing. Her three daughters were all extremely close, and Mina remembers the years spent bringing them up as a happy time.

Mina’s difficult relationship with her own mother never healed, and she died when Nikki was two. “I didn’t trust her,” says Mina. “I didn’t trust her with the kids, and she didn’t like me for it.”

Mina’s sister Anne, however, doted on Bibaa. When the murder happened, she was being treated for stage 4 lymphoma; she died a few months afterwards, aged 71. Another tragic layer piled onto a lifetime of tragedy. “I believe that was the final straw,” Mina says.

Her sister’s funeral was held at the same crematorium where Bibaa and Nikki had been laid to rest and, heartbroken, Mina felt unable to attend because of the emotional damage it would provoke.

The unrelenting agonies in Mina’s life have now resulted in a diagnosis of PTSD. She admits it is a continual struggle to keep going, but the important work she is doing with others is what drives her.

Over recent years, she’s developed a strong connection with the parents of Sarah Everard. When Mina called out the difference in the public response to Sarah’s murder – Sarah having been a white, middle-class woman – and the reaction to the murders of Bibaa and Nikki, she was anxious that they would think she was failing to recognise their pain. She needn’t have worried. Sarah’s parents fully supported Mina, and they have bonded in their determination to end the misogyny that runs deep in the police force.

“We are an elite group you really don’t want to be part of,” says Mina. “You become instantly, and always, connected. It works because you don’t have to put into words what you feel. It doesn’t feel like a reminder of each other’s pain. When we are together, we feel bolstered.”

The other thing that keeps her going is her family. Mina jealously guards the privacy of Bibaa’s daughter, who is now in her late twenties, but says she is doing well. Mina also has a four-year-old great-grandson, born a few months after the murder, who is thriving.

She is wracked by a constant torment and the sense that, if only she could have given her life in place of her daughters, she would have done so “again and again”. But that is what Mina Smallman has been left with, and she vows to use it to keep fighting the system that so badly let not only her and her daughters down, but all the other women still waiting for justice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments