‘The Met breaks my heart’: The dramatic decline of Britain’s biggest police force, and how it could recover

The fall from grace of Britain’s largest police force has been stark, writes Tom Harper. How does the Met get itself out of this hole?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As former Metropolitan Police officers, Bethany and Paul Eaton are well aware of the disaster that has enveloped Scotland Yard: violent crime is soaring across London and thousands of officers have left the force.

Yet even they were shocked by the way police responded when their home in Chislehurst, southeast London, was burgled in 2019. The couple were on their way back from a family holiday in Dubai when their childminder called to say the back door had been smashed in.

The Eatons, who now run a vegan yoghurt business, asked a neighbour – a Met civilian employee – for help and she immediately called the police. It was at this point that the first signs of institutional inertia emerged, when the operator who answered the call replied: “I’m sorry but you don’t have an appointment, so officers will not be attending the scene today.”

To this day, Paul, who worked as a Met response officer for almost 20 years, does not understand how he was supposed to book an appointment for a burglary that had not yet taken place. His friend was also confused. “My neighbour was flabbergasted and somewhat scared, not knowing if anyone was still in the house,” Paul says. “She was told police would attend within 24 hours.” The neighbour tried to persuade the operator that the Met should come, not least as she had seen three police cars dawdling outside the local café around the corner. The person on the end of the line replied that was “just not police procedure these days.”

In the end, the only person willing to help the neighbour secure the crime scene was a passing Ocado delivery driver, who checked to see whether the burglars had fled. When Londoners’ emergency service of last resort is an online grocer, we can probably agree there is a problem.

The Eatons’ experience is sadly all too familiar for London’s eight million residents, and millions of others across the country. They have seen the capabilities of local forces undermined by a combination of budget cuts and a dangerous passivity that has been allowed to evolve among the people in blue.

Before the unprecedented Covid lockdowns skewed crime rates, a national rise in murders and manslaughters in 2020 was mainly driven by a 28 per cent rise in offences in London (67 to 86).

The number of knife crimes in England and Wales also rose to a record high, partly driven by a 7 per cent rise in London. This was 51 per cent higher than when data of this kind was first collected in 2011 and was the highest number on record. By contrast, the proportion of crimes in England and Wales that are solved has fallen to a record low.

These damning statistics are partly fuelled by a decision taken by the Met in 2017 – a decision that would have been laughed out of the police canteen thirty years ago. The “crime assessment policy”, drawn up by senior officers, ordered police to shelve investigations into hundreds of thousands of crimes each year, including burglaries, thefts and some assaults. The move has amazed former leaders of the force. “The violence and the knife crime and the death rate is deeply concerning,” Sir Paul Stephenson, a former Met commissioner, tells me. “The downscaling of the seriousness of household burglary means it’s almost seen as some sort of social misdemeanour. I think invading people’s homes should be treated as a heinous crime.”

The measures were a response to historic government curbs on police spending that have been implemented since 2010. Scotland Yard was attempting to save £400m by 2020, in addition to the £600m the force had already lost from its £3.7bn annual budget.

The fall in standards has helped to create a noxious culture that seems to penalise success and celebrate failure. Fewer and fewer police officers know how to solve crimes

Just before Mark Rowley was announced as the new commissioner in July 2022, Scotland Yard suffered the ignominy of being placed into special measures, a status commonly applied by regulators of public services to failing schools and hospitals, not one of the world’s most famous police forces.

I have covered Scotland Yard as a journalist for 16 years, beginning not long after the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes, an innocent Brazilian killed by Met Police officers after being mistaken for a terror suspect in 2005.

Despite the shambles of that operation, the Met at that time still seemed immensely powerful, was largely trusted, and was not to be trifled with.

Since then, reporting on Scotland Yard – and British policing in general – has been akin to witnessing a slow-motion car crash. Barely a week goes by without the Met finding itself at the centre of a new crisis, lambasted by MPs and criticised in once-friendly newspapers.

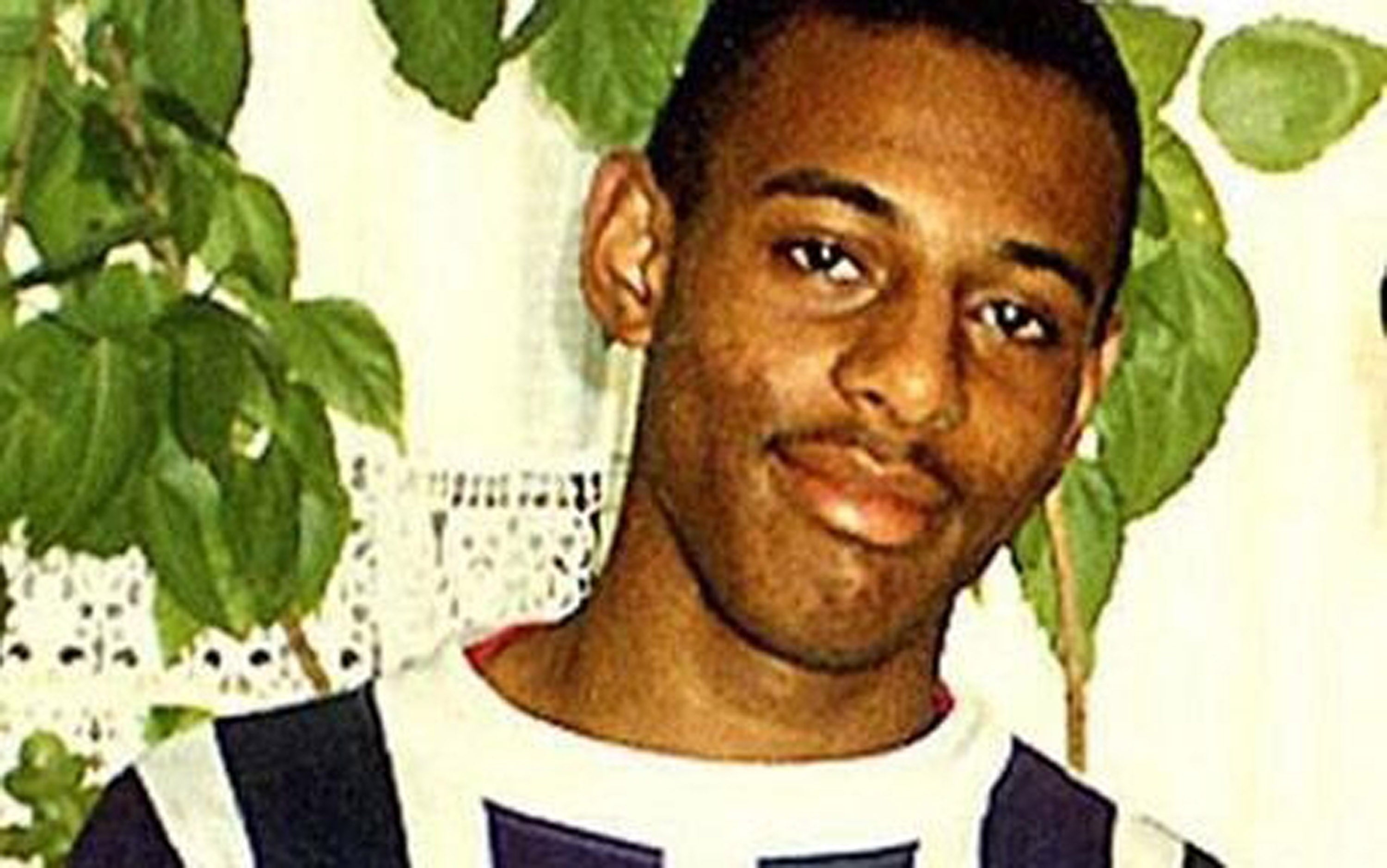

With scandals including Plebgate and the arrest of Damian Green, the force has been dragged into open warfare with the electorally-dominant Conservative Party. After the phone-hacking furore, its close ties with the press were also shattered, leading to increased scrutiny of corruption and incompetence in murder cases such as Stephen Lawrence and Daniel Morgan, where the police’s search for the truth was so limp they seemed deliberately designed to fail.

In recent years, the media also started to publish and broadcast stories exposing rotten corners of society that had long been ignored by the police; the rise of “modern slavery” offences and the industrial-scale abuse of children – from Asian child-grooming gangs to Jimmy Savile. When disturbing details of these “new” offences spilled out into the public domain, the government ordered the police to make them as much of a priority as traditional crimes such as violent offences and drug trafficking. Scotland Yard and other forces quickly became overwhelmed

The perfect storm facing policing also includes the consequences of mass internet use. The digital explosion in the 21st century ushered in a new era in cyber and online offences, estimated to cost UK victims £10bn a year. Soon, the police were so swamped that officers were allowed to record them differently from other types of crime, which kept them off the official crime statistics by which forces are measured.

For years, in fact, until 2017, the government simply didn’t recognise online fraud and computer misuse offences. When the Office for National Statistics, which compiles the Crime Survey for England and Wales, finally started to do so, the change captured 5 million more offences in the previous 12 months alone, doubling the overall crime rate overnight.

Demoralised and depleted in numbers, the Met is a shadow of its former self.

This is a tragedy that harms each and every one of us, not least because so many of the 32,000 police officers inside Scotland Yard perform heroic acts on behalf of the public every day. Former detective superintendent John Sutherland was forced to retire early with crippling depression and has become a powerful advocate for the good that police officers do. But even he accepts that the current malaise is partially self-inflicted. “There are times as a police officer when I just want to bury my head in my hands,” he says.

I have written a new book, Broken Yard: The Fall of the Metropolitan Police in an attempt to explain how London’s renowned police force got itself into this sorry mess – and how it might get itself out of it.

For a start, the Met could get back to basics with its training. Over the years the Met has downgraded the role of the plain-clothes CID detective, an elite band of investigators who were put through rigorous training in order to be able to solve the most complex and serious crimes.

Today, they are a dying breed. The fall in standards has helped to create a noxious culture that seems to penalise success and celebrate failure. Fewer and fewer police officers know how to solve crimes. Institutionalised incompetence had been added to institutional racism and widespread corruption.

Tony Nash, a former detective who rose to be a borough commander, tells me: “I had really good on-the-job training. Now, it’s armchair detectives. A lot of people coming through the process are not getting that exposure to proactive work, and they shy away from it.

“We have programmed some very good people to become investigators but they have become almost sedentary. They are very fond of picking up the phone and it’s all become very reactive.”

Most of the best investigators in Scotland Yard are also largely forced to languish at the rank of detective constable or detective sergeant, each working on dozens of serious cases. The result is that the officers best suited to preventing and detecting crime do not progress to strategic leadership roles, which are largely filled by officers from the uniformed branch. Imagine an NHS that refused to promote surgeons beyond foundation level, with complex open-heart procedures being overseen by administrators.

Like Tony Nash, former commander Roy Ramm is one of the few detectives to rise to a senior level in the Met. He too is appalled at the quality of senior officers at Scotland Yard. “They are professional police managers who have risen through the ranks without trace, without ever standing in the witness box and giving evidence.

“This breed of political senior officers has done immense damage to policing.”

Bob Quick, a former detective, rose higher than either Ramm or Nash. In 2008, as the Met’s assistant commissioner in charge of specialist operations and counter-terrorism, he was effectively the third most senior officer in Britain.

He also served as national lead for workforce development so he has a unique insight into the collapse of the detective class. “In the 2000s, there was a failure really – despite the best efforts of many people, including myself – to underline the importance of the detective role. There was a strong push from government to dumb down the training.

“There was a homogenisation of police training and police careers; they were all seen as level pegging,” Quick tells me. “It was a bit like saying if you are ground crew for British Airways there’s no reason why you can’t be a pilot. So we will train you to be a pilot.”

Across England and Wales there is an estimated shortfall of 5,000 detectives. The Met alone is officially down by 700, although sources tell me the figure is far higher. “People are leaving in their droves,” one senior Met source tells me. “At one stage there were 90 qualified, experienced detectives leaving the service every month.”

Does the fish rot from the head? Scotland Yard’s management is now being openly questioned by those who once led it

In 2017, Scotland Yard announced that new recruits to the Met could become detectives without having to spend two years as a uniformed bobby on the beat. Following a year’s training, they can now work on rape cases – and after two years they can apply to join the murder squad or even the counter-terrorism command.

The malaise leads to catastrophes such as Operation Midland, one of the most ill-fated inquiries in the Met’s long history. In 2014, Scotland Yard electrified the nation when it announced that it was investigating a series of murders during child sex abuse parties involving ministers, spy chiefs and prominent military figures. A former public sector worker who police gave the pseudonym “Nick” had come forward to allege that he was sexually abused as a child by a “VIP paedophile ring”. His attackers, he said, had included the late prime minister Sir Ted Heath, former home secretary Lord Brittan, D-Day hero Lord Bramall and Tory MP Harvey Proctor.

“Nick” turned out to be a paedophile himself and a serial fantasist. He was eventually convicted of perverting the course of justice. A judge-led review subsequently identified an astonishing 43 separate blunders by police officers and said the reputation of the suspects had been “shattered by the word of a single, uncorroborated complainant”.

During the research for the book, Lynne Owens, the long-serving director general of the NCA who stepped down in October 2021, also openly admitted that law enforcement is overwhelmed by “new” threats from cybercrime, modern slavery, organised immigration crime and the dark web – which all have to be dealt with alongside the more traditional work fighting drug traffickers and gun runners.

She told me that terrorism is rightly treated very seriously by policymakers but, in reality, the threat pales into insignificance compared to organised crime. In 2013, the NCA estimated that organised crime cost the British public £24bn every year. Owens, who rejoined the Met as deputy commissioner in September 2022, tells me the figure was probably an underestimate and the phenomenon has grown since then.

She points out that the annual funding of around £377m handed to the NCA is far less than the billions available to counter-terrorism, despite the former being a greater national security threat.

Does the fish rot from the head? Scotland Yard’s management is now being openly questioned by those who once led it. Quick, a one-time boss of departed commissioner Cressida Dick, believes that the force is in a “bad way”.

“People of my generation, the people who left in the late 2000s when the police were just about still intact, look on at what has happened over the last decade in horror.”

He is critical of the silence of chief police officers in the face of the savage budget cuts. “They knew full well that they would result in people losing their lives, and that’s exactly what happened in London,” he says. Roy Ramm, the former commander in charge of the Flying Squad, puts it more succinctly: “Cressida was unique in lots of ways but she’s not the first Dick we’ve had as a commissioner.”

In July 2022, Mark Rowley, who had lost out in the race for commissioner five years earlier, was appointed as Dick’s replacement. He immediately pledged to implement urgent reforms.

One simple measure Rowley might consider is to ditch the extraordinary defensiveness. From Stephen Lawrence to Operation Midland, the Met tries to defend the indefensible, arguing against a reality that seems all too clear to others. Blatant lies and cover-ups are counter-productive and sap public confidence in a vital institution.

Like many police officers I spoke to in the course of writing this book, former detective chief inspector Clive Driscoll – who solved the Stephen Lawrence murder – is genuinely upset about the travails of an organisation he still holds in high regard. “The Met breaks my heart at the moment,” he said. “It is in a bubble. It doesn’t tend to listen to anybody outside. It knows best until it goes horribly pear-shaped, then [it has] to apologise.” Driscoll says that “people that would normally be 100 per cent behind the police” are worried, yet senior officers “can’t understand why”.

“Someone needs to save the Metropolitan Police Service from itself. Never mind the people that want to attack it. They need to save it from itself.”

In his original nine principles of policing, Sir Robert Peel, the founder of the Met, wrote: “The police are the public and the public are the police.” The power of the police depends on openness, honesty and public consent. Recent commissioners seem to have forgotten these sacred words. For some, the most important change would be for Met chiefs to shelve the ruinous notion that the Yard’s reputation takes primacy over all else. Ignore political intrigue. Ignore the media mêlées that blow up from time to time. Instead empower police officers to follow the evidence, without fear or favour. Clive Driscoll now lectures young recruits and is troubled by some of the complaints he hears.

A lot of them say “‘Oh, I wouldn’t like to do that in case someone says I’m a racist’, or this, that and the other. And I say: ‘Well, look, if you are honourable and you are following an investigation, who gives a toss what they called you, because at the end of the day that will shine through, that you followed your investigation.’”

For Driscoll, the solution is straightforward. “If you are honest and honourable and do your job, then people will support you.”

‘Broken Yard: The Fall of the Metropolitan Police’, published by Biteback, is released on 4 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments