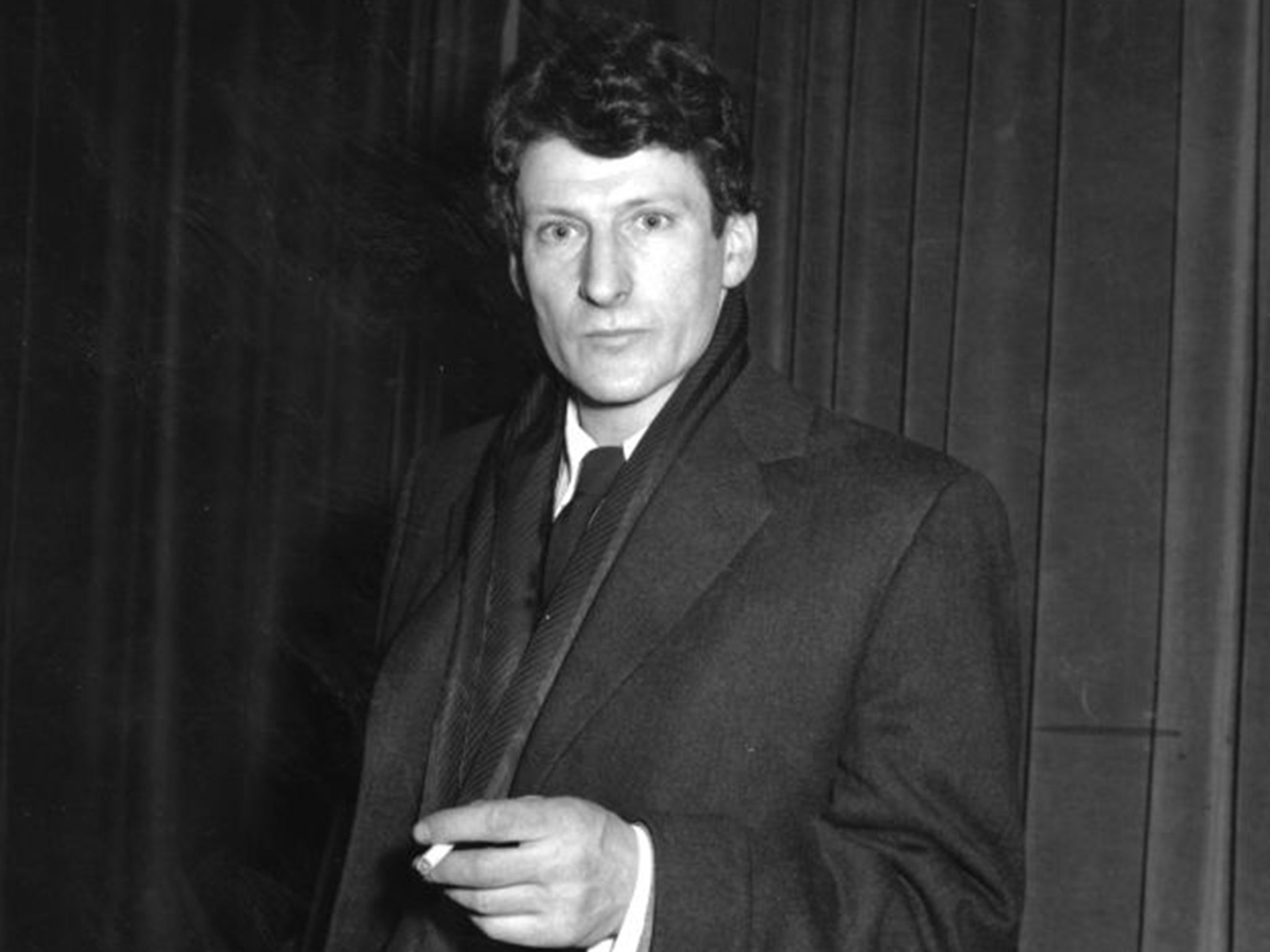

Lucian Freud: Author suggests artist carried out Kray-style revenge on East End chancer who impersonated him

Could Freud, one of the greatest and most influential artists of his era, have been responsible for the attack?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One afternoon, in the early 1960s, a Russian émigré called Alexander “Shura” Shihwarg opened the door of his home in Chelsea in London to find his friend, David Litvinoff, beaten and bloodied.

Litvinoff explained that two men had visited his flat overlooking Kensington High Street and knocked him unconscious with a single punch. When he awoke he was naked, covered in blood and tied to a chair that was hanging upside down from the railings of a roof terrace.

The first thing he heard was music: beneath him a group of CND protesters was marching down the street, oblivious to the terrified man suspended a few storeys above them.

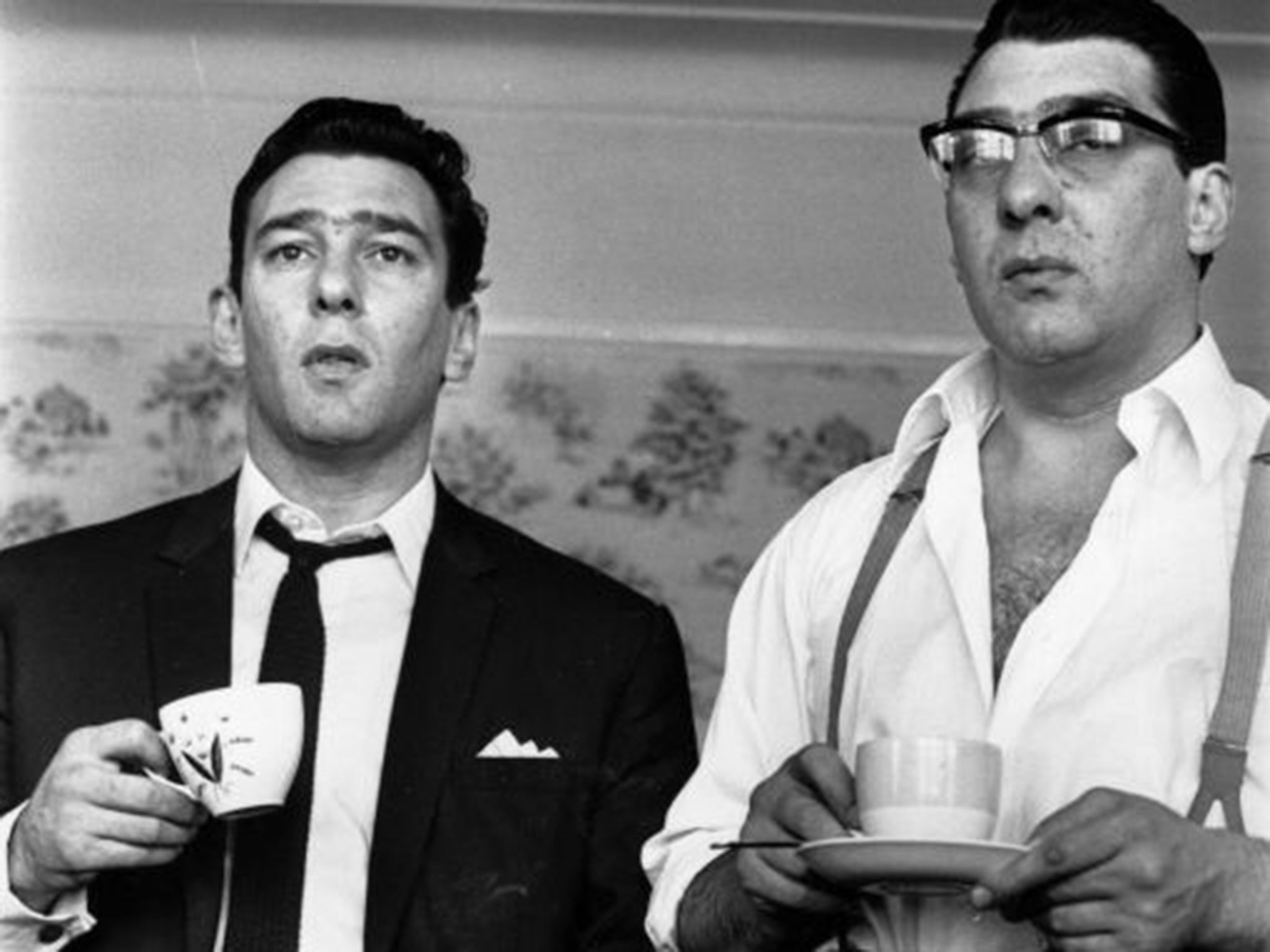

At the time, the brutal attack was attributed to the Kray twins, the notorious London gangsters with whom Litvinoff – who straddled the worlds of fine art, rock’n’roll and crime – was well acquainted. Litvinoff had gambling debts, it was said, and the Krays had sent their associates to teach him a lesson.

But Litvinoff suspected someone else: the painter Lucian Freud. He had been friends with the artist, albeit briefly, but they had fallen out badly. Badly enough, Litvinoff told a string of friends and acquaintances, for Freud to organise a reprisal.

“He [Litvinoff] told me he expected [his attackers] were cronies of Lucian’s,” says 93-year-old Mr Shihwarg, who recalls vividly his friend’s frightening appearance that day. “I was horrified to see him – he was covered in blood.”

Could Freud, one of the greatest and most influential artists of his era, been responsible for the attack? Keiron Pim, the author of Jumpin’ Jack Flash, a new book about Litvinoff – a mysterious character who provided a conduit between Sixties artists, rock stars, including the Rolling Stones, and London’s criminal underworld – said many of Litvinoff’s peers believe it was possible.

“To a good many people this was just an accepted fact about Lucian,” said Pim. “If you mentioned Litvinoff to them they’d say, ‘You know Lucian had him hung upside down over Kensington High Street’.”

Both Freud and Litvinoff were well acquainted with the Krays. The artist often gambled at Esmeralda’s Barn, the brothers’ Knightsbridge club, and dined with them on a regular basis; Litvinoff, who grew up in London’s East End, allegedly procured young men for Ronnie Kray.

Both Freud and Litvinoff enjoyed the notoriety their association with the gangsters bestowed on them.

David Cammell, who was friends with Litvinoff and knew Freud socially, believes the idea that the artist organised the attack using his criminal connections is “very possible”.

“I knew Freud had a dark side,” said 78-year-old Mr Cammell, who was the associate producer of Performance, the 1970 film that starred Mick Jagger and was co-directed by Mr Cammell’s brother, Donald. “I was at a party and Lucian was there and I said, ‘I’ve just been having lunch with a friend of yours, David Litvinoff’. And he [Freud] said, ‘He’s no friend of mine’, and I’ve never seen a more evil look. I think he was perfectly capable of doing something dreadful.”

Freud and Litvinoff became friends, of sorts, in 1954. The artist, then 31, discovered that 26-year-old Litvinoff – who bore a certain resemblance to Freud – had been passing himself off as the famous painter in Soho bars and clubs and charging drinks to his account.

While Freud had “the urge to hit Litvinoff”, he had a “stronger desire to paint him,” writes Pim. Litvinoff sat for Freud in his studio at least 30 times and the result was a striking portrait that was provisionally titled “Portrait of a Jew”. But when the picture was unveiled at a Bond Street gallery in 1958, Freud had changed its name to The Procurer, a wildly provocative name given Litvinoff’s reputation for providing sexual partners for his powerful friends.

Litvinoff was incensed. “I remember his fury at seeing that portrait at Freud’s exhibition,” says Mr Shihwarg. “I’d never seen him so angry – he was spitting with rage.”

Litvinoff threatened to sue Freud, but backed down. He took his revenge by stealing a cherished zebra’s head – a prop that appears in at least two of Freud’s paintings – from the artist’s flat. From then on there was no love lost between the artist and his erstwhile model.

William Feaver, Freud’s friend and biographer, acknowledges that the painter had “lots of dodgy friends” at the time, but pours scorn on the idea that he might have orchestrated Litvinoff’s beating and torture.

“Lucian wasn’t an organiser of violence at all,” he says. “I think he regarded Litvinoff as an irritant and a rather a funny irritant at times.”

The writer believes that Litvinoff’s suspicion that “Lucian’s cronies” were responsible for the attack was probably Litvinoff “dropping names”, He says: “Litvinoff’s whole life is surrounded by a buzz of inaccuracies often generated by himself.”

The truth is unlikely to emerge. Litvinoff overdosed on sleeping pills in 1975, while Freud died in 2011 at the age of 88.

“Fundamentally, Freud disliked Litvinoff,” said Pim, “but his great redeeming feature for many people – the reason they tolerated him – was that he was extremely funny. There was at least a part of Freud that rather enjoyed his company.”

Jumpin’ Jack Flash by Keiron Pim is published on 28 January by Jonathan Cape

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments