The bizarre true story of when the UK military tested LSD on Royal Marines

‘One hour and ten minutes after taking the drug, with one man climbing a tree to feed the birds, the troop commander gave up, admitting he could no longer control himself or his men.’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the kind of clipped BBC English that more frivolous generations associate with comic Harry Enfield's Mr Cholmondley Warner, the narrator explained how the LSD was given to the Royal Marine Commandos “in a cup of wartah.”

“Twenty-five minutes latah, the first effects of the drug became apparent. The men became relaxed and began to giggle.”

They certainly did. The black and white footage from 1964 shows the hitherto ferociously well-drilled servicemen lying flat on their backs, helpless with laughter, or staggering against trees, intoxicated by the hilarity of it all, and by the acid.

“One ahr and ten minutes after taking the drug,” intones the narrator, “With one man climbing a tree to feed the birds, the troop commander gave up, admitting he could no longer control himself or his men.

“He himself then relapsed into laughter.”

Perhaps bizarrely, the whole thing was considered something of a triumph.

Ultimately, though, this field exercise conducted by the government’s secretive Porton Down chemical weapons research establishment was the first in a series that would end in failure.

Half a century ago this year, the military’s experimentation with acid ended with the chairman of the Chemical Defence Advisory Board declaring that the idea of using LSD as a weapon of war was “more magical than scientific”.

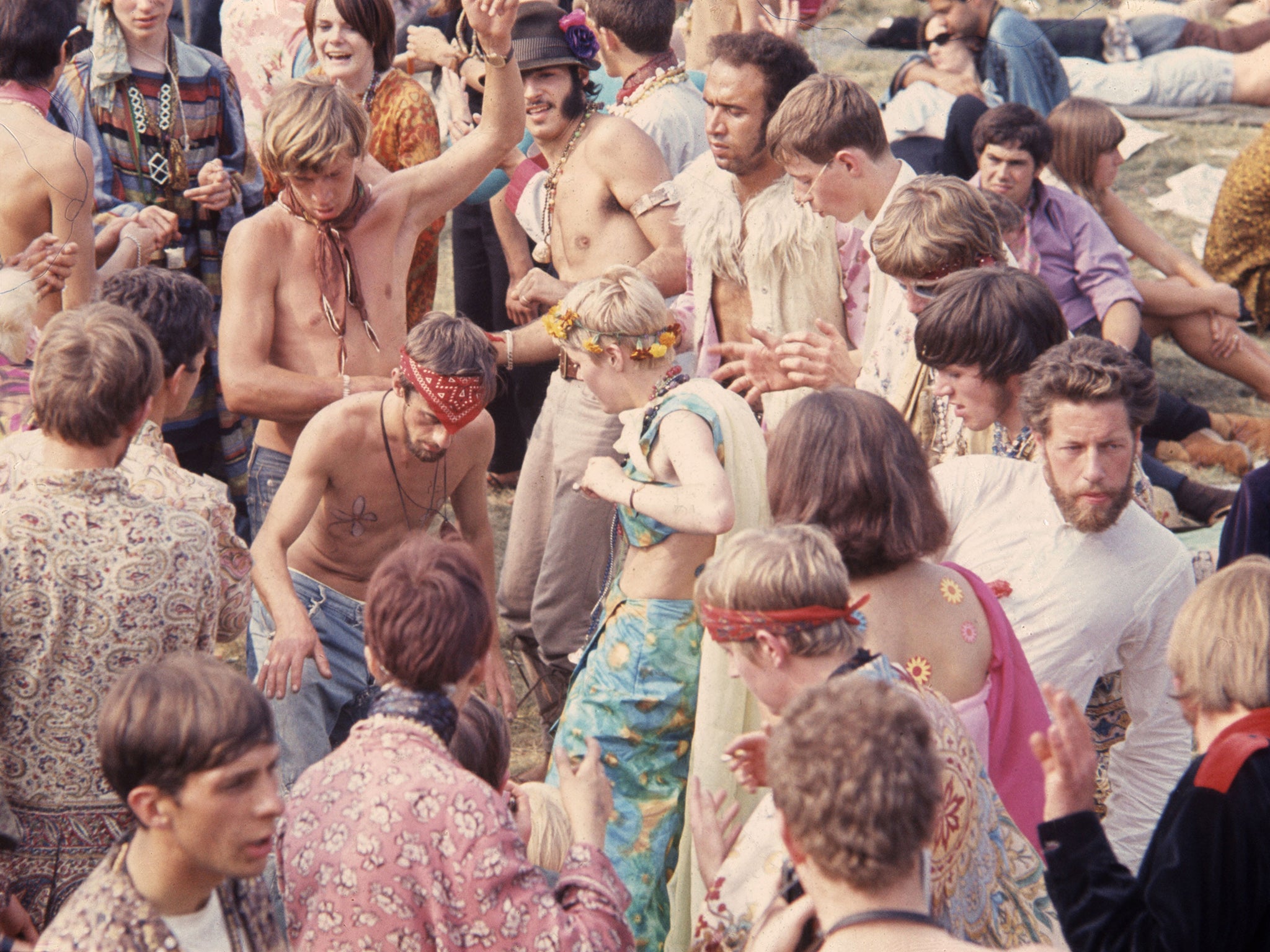

That the British military gave up on LSD in 1968, at the very moment the Sixties counterculture was enthusiastically embracing it, is but one of the ironies.

This was a rare relatively comic interlude in the history of Porton Down, the establishment that recently identified Novichok, the nerve agent developed by Russia, as the substance used to poison former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia.

Before the 1964 exercise, Portdon Down had a far darker entanglement with LSD.

In the early 1950s it had explored the possibility of administering LSD in interrogations as a “truth drug”.

British servicemen were allegedly asked if they would volunteer to help with research into finding a cure for the common cold.

Then, it was later claimed, they were given LSD.

Donald Webb recalled how as a 19-year-old airman in 1953, he volunteered for what he thought would be a “cushy number”, only to be given LSD several times over the course of a week, suffering nightmarish hallucinations: “cracks appearing in people's faces, you could see their skulls, eyes would run down cheeks … You could see things growing on you."

Webb, who said he suffered flashbacks for ten years, was given compensation along with two other ex-servicemen in 2006, although the Ministry of Defence made no admission of liability.

Even more sinister than the LSD “truth drug” experiments, was Porton Down’s use of servicemen as human guinea pigs for testing nerve agents.

In 1953, the same year that Donald Webb said he experienced his LSD ordeal, leading aircraftman Ronald Maddison died aged 20 after an experiment with sarin went wrong.

An initial inquest, held behind closed doors for "reasons of national security", returned a verdict of death by misadventure.

It was 51 years before a second, public inquest overturned that verdict and replaced it with one of unlawful killing by the British government.

By the early 1960s, Porton Down had the same interest in nerve agents, but the focus on LSD had shifted from its potential use as a “truth drug”, to a means of incapacitating the enemy.

In 1994, when the Conservative government was asked about these experiments in Parliament, the modern management of Porton Down was careful to stress that the establishment’s current purpose was to devise defensive measures against enemy chemical weapons attacks.

The answers given in parliament in 1994, however, did not make any explicit reference to what Porton Down’s role might have been in 1964, and some have argued that at the time the UK had an offensive, as well as defensive chemical weapons programme.

Professor Malcolm Dando of Bradford University’s Department of Peace Studies, for example, has drawn attention to the Cabinet Defence Committee meeting of May 1963, chaired by Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan, which agreed to: “an increase in research and development on lethal and incapacitating chemical agents and the means of their dissemination.”

To the British government of the Sixties, in the form of the Advisory Council on Scientific Research and Technical Development, the hope was that LSD and other such chemical weapons could produce a “humane type of warfare”.

The idea seems to have been that “incapacitating agents” could neutralise the enemy without killing him, and perhaps more importantly, without inflicting collateral damage on any civilians who might be present if, for example, the fighting was in a built-up area.

They tried all sorts of things. In 1962 the British noted that their American counterparts were exploring the possibility of weaponising cannabis to make it a battlefield incapacitating agent.

Porton Down had a liaison programme with industrial chemists and academic researchers, allowing it to learn about things like what Guy’s Hospital Medical School was doing with snake venoms.

And according to Prof Dando’s account, by 1964 there was some degree of urgency in the hunt for an effective, “humane” incapacitating agent.

In November of that year, General Sir John Hackett, Deputy Chief of the General Staff, told a meeting of the Advisory Council on Scientific Research and Technical Development: “It was very desirable to find a safe incapacitating agent ... General Staff Targets had been issued.”

And so on Tuesday, December 1 1964, 17 volunteers from 41 Royal Marine Commando were given water containing 200 microgrammes of LSD.

There would eventually be three such field exercises. Someone at Porton Down had the sense of humour to recognise that the letters LSD were also the pre-decimal symbols for pounds, shillings and pence – hence the codenames Moneybags, Recount and Small Change.

Moneybags, the December 1964 exercise, was the first.

After drinking their LSD, the marines “embussed” to Porton Down trials range for a small-scale field exercise simulating the kind of counter-insurgent fighting experienced during the Cyprus emergency.

It did not proceed with the normal military efficiency.

At least two different commentaries seem to exist for the footage filmed by Porton Down scientists that day. In the version acquired by the Imperial War Museum, the sober narrator explains: “At 1140 the first effects of the drug make their appearance. Two marines are reported to the troop commander for insubordination.

“The other men … relax and begin to giggle.”

The film pans from a prone, giggling marine to an almost destroyed tree trunk, as the narrator observes: “Men have relapsed into laughter and inconsequential behaviour, though they are still capable of sustained physical effort. This man nearly succeeded in felling this tree using only a spade.”

After it ends with one man up a tree and the troop commander helpless, the marines are taken to hospital for “awbservaytion”:

“The troop commander is experiencing one of the characteristic effects of the drug. Everything he looks at appears to be patterned. While looking at the white ceiling, he describes geometrical patterns which are coloured and three dimensional. They appear to move in and out of each other…”

More worrying was the anxiety etched on the face of one marine who appeared to be having a bad LSD trip.

“For three hours,” the commentary explained, “He was completely divorced from reality. Even now, three and a half hours after the administration of the drug, he does not know what he is doing or where he is.”

The marine can be heard telling the medical observers: “No, I’m not going to die … No, I’ve not died mate.”

The commentary does say that by the next morning he had recovered to the point that he was “capable of carrying out his normal duties.”

But it is not entirely clear what long-term effects – if any – there were on the marines.

When questions were asked about this in Parliament in 1994, the official response was that there was “no evidence of any deterioration in the health” of the 72 service volunteers involved in laboratory LSD tests from 1962 and in the Moneybags, Recount and Short Change field exercises.

Despite LSD now being a Class A drug, in 1994 MPs were told, via information supplied by Porton Down’s then chief executive Graham Pearson: “There is no evidence to link controlled administration of a single dose of pure LSD with any long-term effects.”

Back in 1964, the obvious incapacitation of the marines seems to have been considered an encouraging start.

There were, however, some concerns.

Andy Roberts’ book Albion Dreaming states that after Moneybags, and amid growing public anxiety that led to LSD’s recreational use being banned in 1966, the Applied Biology Committee considered delaying the trials “until more is known of the persistence of mood effects.”

The committee also noted “disconcerting results in one particular case of multiple self-administration and concern over possible addiction”.

Presumably, one of the Porton Down scientists had grown rather too fond of the laboratory stock.

But the needs of “humane warfare” seem to have come first. The 1965 annual report of the Advisory Council on Scientific Research and Technical Development stated: “Experiments on this humane type of warfare should be pressed forward with all speed.”

And so in September 1966, with the ban on medical, as opposed to recreational use of LSD still seven years away, the Recount field exercise began, to be followed, in January 1968 by Small Change.

They seem to have achieved similar results to Moneybags.

Interviewed while being monitored in hospital after Recount, one soldier says: “Things started to seem a bit unreal … Not able to concentrate, chocolate tasted bitter, similar to when first getting drunk, just wanted effects to wear off.”

Film of Small Change shows volunteers from A Company, 1st Battalion Staffordshire Regiment, becoming as relaxed as the marines had been in 1964.

But as with Moneybags, amid the cheerfulness of most of the group, there were signs that a few had been disturbed by the experience.

Asked how he felt, one sergeant replied: “Most confused, very unpleasant.”

The scientists involved in Small Change concluded that LSD had, again, successfully reduced unit efficiency.

But by now practical concerns were being raised about how the drug could be deployed in combat.

Persuading friendly volunteers to drink water they knew might be spiked was one thing, getting LSD into a hostile enemy on the battlefield was another.

The Porton Down scientists were finding LSD hard to deliver as a gas. And to be effective in this form, the doses needed to be high – worryingly high.

The dream of a “humane”, casualty-free incapacitating agent was dying.

As Prof Dando has suggested, the British were discovering what was allegedly demonstrated to tragic effect during the Moscow theatre siege of 2001.

The Russian authorities are believed to have tried using something similar to fentanyl – the opioid now contributing to huge addiction problems in the US – in the hope of incapacitating the Chechen hostage takers.

The alleged result was that scores of hostages were killed by the effects of the drug.

Perhaps then the right decision was made in 1968, when after Small Change, Professor R. B. Fisher, chairman of the Chemical Defence Advisory Board, circulated a paper advising: “The notion of an incapacitator is a little more magical than scientific.”

The field trials of LSD were over.

The military left the experimenting with acid to the hippies, who by now were busy trying to prove that LSD was for making love, not war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments