The 7/7 bombings: Seven survivors, responders and investigators on the day that London bled

The terror attacks across London on 7 July 2005 killed 52 civilians and injured more than 770, sending shockwaves around the world. Now, 20 years on, a new documentary tells the minute-by-minute story of that fateful day. Those caught up in it tell Zoë Beaty what happened next...

On the morning of 7 July 2005, London stood still. At 8.50am, as commuters went about their daily routines, three suicide bombers – at Aldgate, Edgware Road and Russell Square stations – detonated deadly explosives on the Tube network. Within the hour, at 9.47am, a fourth device exploded on a London bus. The attack, carried out by Islamist terrorists, killed 52 and injured more than 770.

It’s now 20 years since the attack but its impact can still be felt. For many, grief, fear and irrevocably changed lives are still a daily reminder of what happened that day.

Here, ahead of a new BBC documentary airing on 5 January, seven survivors, responders, investigators and politicians, all affected by the blasts, tell their own stories of the days, weeks and years shaped by 7/7. Some have shown astonishing resilience; for others, difficult lessons have been learnt. All of them are connected by something inexplicable: the strength of the London community in the face of the worst of humanity.

Julie Nicholson’s daughter Jenny, 24, an advertising executive, died in the explosion on the Circle line at Edgware Road

It had been around 12 hours since I first realised Jenny was missing when I took a shower in the early hours of 8 July 2005. I took the radio into the bathroom with me – just in case some news came through. There was a moment when I stepped out of the shower and I cleaned the mist from the bathroom mirror and just had this horrible sensation of something having gone from me. I panicked a bit and thought, no, she has to be alive. She’s got to be out there somewhere.

The hours before then had been fraught. I had been away in Anglesey, north Wales, with my parents when we first heard that there’d been an incident and Jenny was missing. She’d been texting me the day before, excited about the Olympics bid, as had my other children. The next day we woke up to sunshine and decided to go for a walk on the beach. We had no phones with us, of course, so we were oblivious until my daughter Lizzie, at home, telephoned me to say she was worried. She couldn’t get hold of Jenny – and I needed to turn on the TV.

The day took on a new purpose: I wouldn’t settle until I knew she was safe. London had been shut down, so we couldn’t travel there – every part of me wanted to be beside her in every possible way that I could, emotionally, physically; I needed to find out everything about what happened to my daughter. When the hotline for missing or injured people opened, I called and the waiting game began. The following morning I got the train to London at 6am and by then we knew that any survivors had been taken to the Royal London Hospital. Jenny wasn’t one of them. She had been killed on the Circle line at Edgware Road station on her way to work. She was 24.

Grief can do strange and horrible things to your mind, your body. After the immediate first wave, I saw that I wasn’t the only one affected. I wasn’t the only one grieving. Her siblings also had their grief, her grandparents and friends. Actually, we were all in it together, though we were grieving differently and independently.

Any parent who has lost a child in any circumstance at any age will tell you that 20 years is no different from 17 years to five years to 23 years. But at some point, you have a choice as to whether you are going to live or whether you’re going to give up and turn your face to the wall. I owed it to Jenny and to my living children to live as full and as good a life as possible. And that’s what I’ve tried to do.

Grief has now taken on a preciousness because the grief I have is about the precious daughter that I had. As a priest, grief is part of my trade and I say to myself as I say to others that you have to make room for it, embrace it. I tried to turn grief into something that I didn’t wallow in, but something about memories. It becomes about all sorts of things: what would she be doing now? Would she have children? What would her hair look like? Things like that.

Maybe as a priest, there are those who feel I should forgive my daughter’s killer. As a mother, I say absolutely not. Perhaps if Jenny had survived she might have found a way to forgive but that’s not my place. What I have done is reconcile myself to the facts of what happened.

I will feel the loss and the absence of her until the day I take my last breath. But I can also cherish the wonderful person that my daughter was: her laughter, her kindness and her love for her family and friends. I think she would have gone on to contribute to a better world in some way or another. That’s my inspiration for living.

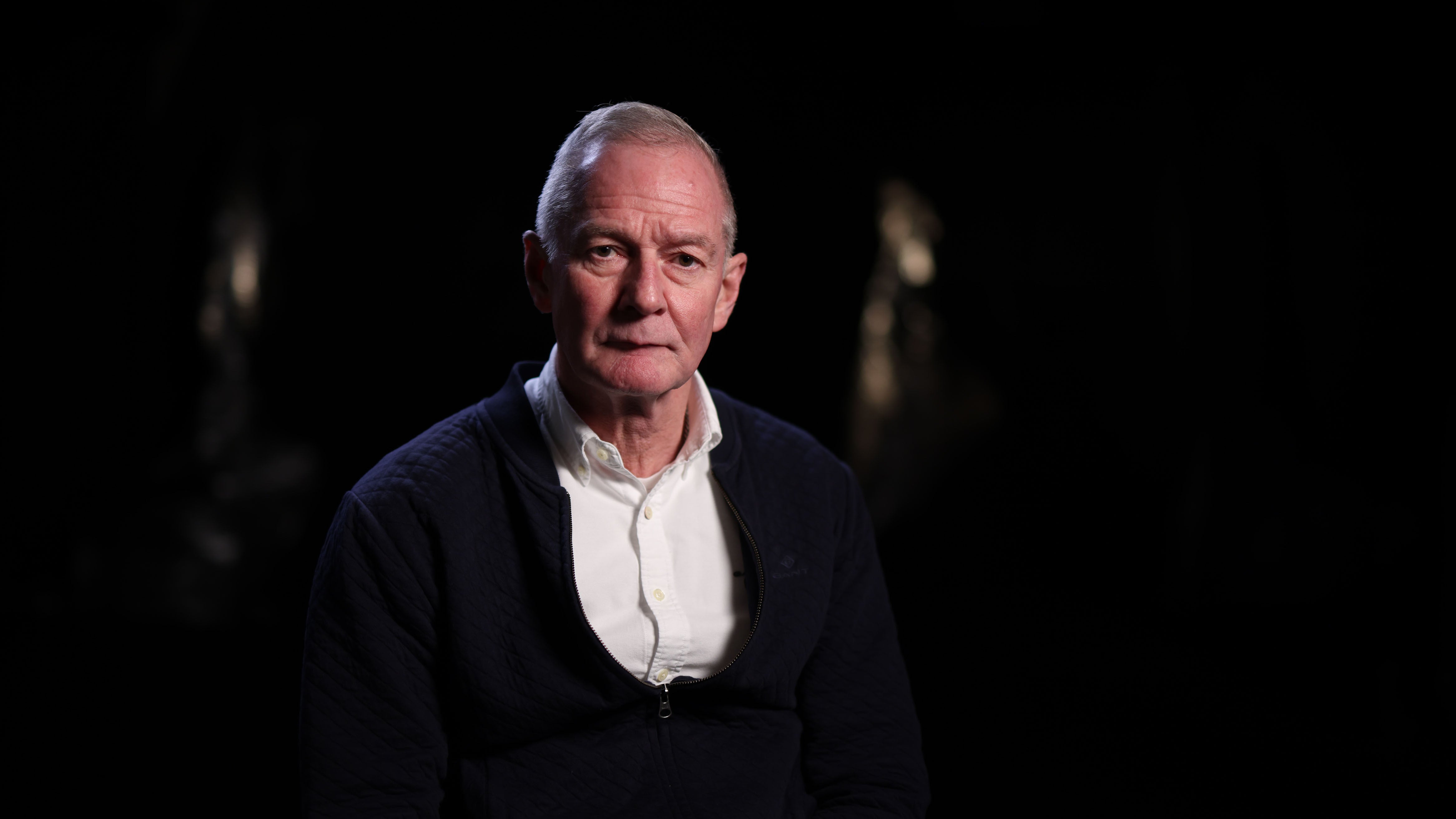

Andy Hayman, consultant and former Assistant Commissioner, Met Police, (2005-2007)

There was a moment, a day or so after the attacks occurred, that has always stuck with me. I’d been going around the different sites, and when I reached the site of the bus bombing, in Tavistock Square, I stood on the perimeter where the police cord was tied. Everyone around the site was busy, harried, but for a moment I was on my own, looking on. Underneath my feet it felt like I was standing on snow, or ice – actually it was broken glass. The splinters of glass and debris reached 100, 200 yards back from the bus with its roof off that I could see in the background. I thought, you just cannot describe this, what’s happened here. There’s victims, there’s survivors, there are families and loved ones and friends. The violence was enormous.

I’d only been at my job for six months or so before the attack occurred. It looked to be a brilliant job on paper: I was responsible for a department called specialist operations, and the portfolio included the protection of the royal family, protection of government administrators and all the visiting diplomats.

The morning of the bombings I’d done my usual routines – get in early, pound on the treadmill for a bit, then to my desk at 9am with two slices of toast with raspberry jam and a banana. Shortly after I got in, my deputy came in to say that there’d been a fire on the Underground. To be honest, I thought, without wanting to sound arrogant, “Thank you, but that’s hardly under my remit.” Little did I know what was about to unfold.

The investigation was on a scale we’d never ever experienced before. A normal major incident room would be literally a room and maybe a side room, whereas this took up two floors of New Scotland Yard. Coincidentally, I’d been on an exercise weekend put on by the cabinet, where you essentially have a dummy run of a scenario that involves Cobra – the emergency committee – where you learn from mistakes you made and rehearse for the real thing.

There was a little saying that many of us used to use when trying to prepare for something that might happen in the future – “you just have to think the unthinkable”, we’d say. And before that event, I don’t think we had.

The biggest challenge was to make sure that we were communicating in a clear, concise way, and it’s accurate factual information – you can’t assume or second guess anything. There was so much to do, and so much at stake. And all the while we didn’t know if this was only the beginning, or whether another terrorist might be out there. I’ll never forget my colleagues who stared at CCTV for so long, who were so tired that the whites of their eyes were bloodshot. But, after days and days of work, they found the perpetrators.

What I think the attacks on 7/7, and the unsuccessful ones on 21/7 did, is that they opened up a new chapter of radical, extremist terrorism. Sadly, all you’ve got to do is look at what’s happened since then – even as recently as the German Christmas market attack – to see that’s true.

The upshot, if you can take one from 7/7, is that the authorities have raised and continue to raise their game. And the community has become more observant, and more active in reporting them. That day and the weeks after it will not be forgotten by me, though I’ve retired from the police now. None of us will forget.

Bill Mann, 60, life coach and survivor, Edgware Road

I remember flying through the air. I had been sitting down on one of the chairs next to the Tube doors, and then I was flying, right across the doorway to the other side of the carriage. My head was clear but one thought: is this it? Is this where it all ends?

My next thought was this: my family, my wife, my four children – at the time my eldest was 13 and my youngest was two – all the things that I wanted to live for. I wanted to see them grow. I wanted to be there to have dinner with them at night, and read them stories; all the things that money can’t buy.

The lights went out and there were burning embers in the air, shattered glass was everywhere. For a few seconds there was screeching from the sound of metal on metal, and then after a second or two everything stopped. The carriage stopped moving, I grabbed a handrail and stood up and there was a very brief moment of absolute quiet. And then the screaming started.

There were two types of screams. The sorts from people who were just hysterical, panicking. But I could also distinguish the screams of people who were in untenable pain, possibly dying. I tried to help people – one woman who thought her hair was singed by fire, an autistic lad who was panicked and talking about getting to college. As I looked down the carriage I could see bodies on the ground, someone performing CPR.

Once the paramedics arrived, I started walking, but my legs turned to jelly; the shock had begun to set in. I carried on down the Tube tracks as best I could and, luckily, since it was Edgware Road station, I began to see some sunlight. I got medical treatment for my (thankfully) minimal injuries – my ear drums were blown out by the blast, I had cuts on my arms and chest and face from the glass. But the psychological scars were far from superficial.

I struggled to process the morning – why did I survive? One week later I forced myself to get back on the Tube from my home in Upminster and practise the journey to work. I knew I had to. The clarity I had in that carriage – of wondering whether I would live or die – propelled me to want to keep living, if I didn’t face this then that was at stake.

I went back to work in financial services for Visa soon after, to a new job that was a big opportunity for me that I didn’t want to lose, and talked about 7/7 hundreds of times. I think that helped. I knew it would take time, and I knew I’d have ups and downs – I did, I went through so many emotions. But that heightened sense of perspective of what I wanted to live for, of what’s important and what’s really not worth worrying about is something I’ve tried to hold on to.

A few years after 7/7 I went through the darkest period of my life, when my wife, Joanne, died of breast cancer. For her, and for our children, who are now grown up, I hold on to it still.

Andy Halliday, firearms officer, Metropolitan Police

I describe the perception of threat a bit like being at a kid’s party when someone holds up a large balloon and a pin, and you’re watching the pin, close to the edge, and waiting for it to burst. That fear, that apprehension – that’s what I was feeling as I went down the escalators of Stockwell Tube station on 22 July 2005. I was waiting for the balloon to burst, waiting for this wall of flames to come around the corner at the bottom of the stairs because the subject we were closing in on – Jean Charles de Menezes – had gone down.

We were part of Operation Theseus, the UK’s largest terrorist investigation at the time in the aftermath of 7/7. As a firearms officer, I was part of the squad tasked with hunting down and facing so-called copycat Islamist extremists, who disrupted London’s transport network with four attempted follow-up bomb attacks two weeks after 7/7 on 21 July.

We’d hardly been able to comprehend that it was happening again, after the shockwaves of the bombings that killed and injured so many just two weeks before, when the radio call came in while we were on standby in east London that day.

Information was coming in about devices that had been dropped on the Tube network but hadn’t detonated. The perpetrators had dropped the rucksack on the floor and legged it. We had found the devices and had subjects running all over London, alongside terrified passengers. There was a real palpable fear in the city; during our short briefing on the morning of 22 July, there was some fear in our squad, too. But this morning’s briefing felt different. I remember looking around the team and thinking that, despite the hundreds of firearms operations we do, this is where we could actually end up in a proper confrontation with a suicide terrorist.

As an armed policeman, I’ve done about 2,700-2,800 operations over 18 years. It can be a bit like playing a sport – there are certain tactics you use, sometimes those tactics have to change because the tactics of the people you’re coming up against change. After 9/11 the whole approach for dealing with terrorism changed – suicide terrorism was very different. You can’t just contain them and talk them out, you can’t reveal that you’re armed police (we were all in plain clothes) because you could cause that bomb to be detonated. The way our operations worked changed. The idea was to take away responsibility from a firearms officer who was actually holding the gun, and give it to a senior officer who would instruct when to shoot.

It wasn’t easy to communicate, the radios weren’t brilliant so we were getting snippets of information. But the job was clear, to apprehend the suspect. We followed him stepping off a bus, and through the barriers of the Tube – afterwards, reports came out that he jumped them, but he didn’t, that was us. After that, at the bottom of the escalator, it was all over very quickly.

As I approached the scene, the public running, screaming, iPods and newspapers being thrown everywhere lasted seconds, before another set of gunshots fired. Then it was suddenly very, very quiet. There was a smell, a mix between being on a gun range and that musty Tube odour. Everything was still, De Menezes was in the Tube and it was very clear that he had been fatally wounded.

We didn’t find out until the following day that Jean Charles de Menezes had been misidentified as a suspect bomber. I remember being taken upstairs to the top floor of that police station, sitting around a table, when a senior officer in uniform came in. He said, “I’ve called you all in to tell you that the man that was fatally wounded yesterday was not Hussein Osman” – one of the four copycat bombers – “but an innocent civilian”.

A feeling of desperation, emptiness and incredible sadness washed over me. It was a real watershed moment for me, being on the periphery of an operation where an innocent man lost his life. It stays with you, the tragedy of it. The Met Police were found guilty of a health and safety offence – rightly so – but the two principal officers were cleared of any wrongdoing, which I agreed with. You can look at these things two ways: bury it and move on, or use it to try and learn.

My personal view is that I’ve used the incident to learn and understand much more about how teams work in subsequent investigations.

Marcelle Stroud, former CCTV coordinator, Metropolitan Police

When the bombs went off, I was sitting in an empty office with one computer and no furniture. The department I’d been drafted in to set up a year before, to find and organise propaganda material, mostly audio and video tapes, was still basically non-existent. Then, overnight, our job became one of the most crucial of the 7/7 investigations.

Where do you start looking for four people, on grainy CCTV, in a city as big as London? We could only begin from the known quantity, which was the location of the bombing. I was sent to the remains of the London bus, its roof gone, to retrieve what footage I could. Between myself and two other colleagues who were drafted in, we then set about coordinating 180 staff to go out and retrieve CCTV from wherever they could.

Railway stations were first, and then every station on every Tube line. Back then there were few cameras that were digital – it was mostly VHS tapes. Where we took a hard drive from somewhere that might have intel nearby – a bank or a jewellery store, for example – we had to give them a hard drive to replace the one we took. After a short while companies who made hard drives were running out of stock.

We were put up in a hotel nearby after that, but we were barely there. Much of it was old-school police work – trawling through evidence, looking for any sort of clues we could find. One day a colleague had been viewing footage from King’s Cross and he noticed four people walking together with rucksacks, not speaking to each other. He called to say it didn’t feel right – he had a hunch – just at the same time as forensics called with an identification for one of the bombers. The identification matched. But once we pinpointed them at King’s Cross, we then had to widen our search to all of the UK, to find out where they’d travelled from.

With our work, we were able to give forensics teams details of exactly where the bombers got on the train at King’s Cross, down to which door handles they touched and what seats they were in. It was incredible to be able to be an integral help – and again during the attempted bombings of 21 July, at Shepherd’s Bush, Oval, and Warren Street Underground stations – when we had to work forwards on the manhunt as well as tracing back.

I’m so proud of what we achieved. The team that I set up was called the National Photographic Intelligence team and, 20 years on, the work we did has a legacy – as a direct result of it, three permanent teams were set up. The work we did ad-hoc has been formalised and is now an integral way of gathering forensic intelligence.

Reflecting two decades after the terror of it all has been cathartic. Speaking about it again has unleashed a lot of emotion that I didn’t realise was there. I’m retired from the police now, and quite honestly I don’t talk about it because I suppose I think normal people don’t want to know. And there was so much going on that never hit the press. I’m glad the general public didn’t know about it because they’d never step outside their doors. But it’s been cathartic to relieve it a little, to remember those people who lost their lives in such an abhorrent way, and to remember how much we tried to get justice for them.

Shahid Malik, former MP for Dewsbury, 2002-2010

Back in 2005, I was the Labour MP for Dewsbury, in West Yorkshire, the town where one of the bombers, widely assumed to have been the ringleader, was from. At the time I wrote about things I was asked at that time: what elements in my constituency could have spawned such radicalism? What influences could lead Mohammad Sidique Khan, husband and father, a primary school assistant, to detonate a bomb, killing seven innocent people and himself in the process?

I found myself faced with perhaps the most difficult task I ever had, really, but I knew what I had to do: I had to give a very strong message to [rid] people of any notion that Islam condones this behaviour, let alone say that these people will go to heaven. I can recall being at the first PMQs after 7/7 like it was yesterday, standing there and telling the house that condemnation was no longer enough. It’s no longer sufficient to condemn them, I said, we have to confront them. So there is no safe space for evil forces to breed into diseased minds.

It was a huge shift. Since 9/11 the Muslim community has felt under siege. So then after 7/7, despite the bombers’ actions being anti-Islamic, there was more fear that there might be backlash. We were starting to see things in different parts of the country – bits of violence, a lot of noise. Muslims were again in a very vulnerable position.

A week after the attacks, I held a two-minute silence with some of my constituents outside of Khan’s home in Dewsbury in memory of his victims. It was met with solidarity. I just had to make sure that I could give confidence to Muslims to stand up and speak against these people, and give confidence to non-Muslims that these extremists did not speak for Islam and Muslims.

I’ll never forget one day when I was walking in Dewsbury town centre when a white couple came up to me and said, “Mr Malik, we’d just like to say that we thought you were just ‘for them’, but now we know you support everybody.” That was a bit of a shocker for me. I thought everybody already knew that. It showed me how much work there was to be done to break down even these more invisible barriers.

Twenty years on, I think we’re in a much better position. The Muslim community has matured and, despite persistent noise from the far right – who, like in the recent riots, are now mobilised by social media – there is more discussion now. But there is still more to be done to break down barriers and make people think in a way where colour becomes irrelevant and where we recognise that we’re all different, but all equal – equally good and equally bad.

There are things that have got better – when it comes to Islamophobia, division and segregation, more people are willing to challenge and less willing to be lazy. Before 7/7, there was a sense that we’d listen to remarks or comments that might be fundamentally wrong and dismiss them as crazy anomalies. Afterwards, I think we realised that words can lead to deeds, and those deeds can be deadly.

Martine Wright, 52, a motivational speaker and survivor, Circle line at Aldgate

I’ve always believed in spiritual connections; that there are reasons for the things that happen to us. On that day the scale of humanity was present: at one end, the most selfish, heinous acts; at the other the most generous and selfless care. There are now many scars on my body – I lost both of my legs in the attack, and almost lost my left arm, on which I had to have a skin graft. A few years after it was done doctors asked me if I wanted that scar removed, but I said no: it looks like a pair of lips. I believe it’s where guardian angels kissed me that day.

To me, it’s a reminder that I’m a product of people’s bravery that day. When you get on a Tube one morning buzzing because London has won the 2012 Olympic bid the night before, then wake up eight days later as a terrorist victim and double amputee at 32, you need something to hold on to, a reason, to make sense of it all.

I have this memory of being in the hospital bed, looking down to see half of my body gone and feeling distraught. I was thinking, why? Why me?

I wasn’t meant to get that train, on 7 July. My usual route to work as an international marketing manager on the Northern line was down due to a signal failure, so I had a sliding doors moment: I could have gone and caught the bus, or gone on to Moorgate and got the Circle line.

I started running up the escalator at Moorgate when I saw the Tube coming into the platform and I thought, result. I didn’t get on in my normal carriage because I had to be quick, but I made it and started reading the newspaper. I remember thinking, “I have to get tickets to the Olympics”, and then suddenly – in a split second – a blinding light. No sound, none at all, but this great light in my eyes. The bomb had exploded at one side of me, rebounded and then came back at me again.

I was trapped, but I couldn’t work out why I couldn’t move. I lost 80 per cent of my blood over the hour and a quarter I was down there. Someone – I later learned one of my guardian angels, Liz – put a tourniquet on my legs. But I never thought I was going to die. I kept saying, over and over, “My name is Martine Wright. Please tell my mum and dad that I’m OK.” The irony of course is that I really wasn’t ok.

It was two days before my parents found out I was safe, which is torturous to think about. In the end, it was Liz who saw one of my friends on the news, asking for help to find me, and managed to contact them. Once reunited, I spent 366 days in hospital, trying to begin my recovery. I had to move back in with my mum and dad in Barnet, far from my little flat in central London.

I thought I needed to return to my high-flying job in marketing – before I’d been having the time of my life, flying around the world. But I was scared – there was something in my head that was compelling me to use my experience in the bombing for the greater good. Otherwise, all that pain might have been a waste of time. I’d long got over thoughts of “why me” – despite being the most injured survivor in the bombings, I saw how lucky I was to be here. Instead of going back, I started living.

I went to South Africa for six weeks to learn to fly planes to challenge myself (which was not popular with my parents), I started playing wheelchair tennis and then sitting volleyball. Years later, I was picked to represent Great Britain’s women’s sitting volleyball team at the 2012 Summer Paralympics. It was insane to think that seven years earlier, before my life was turned upside down, I’d been sitting on that Tube hoping to get tickets.

People think that, through all of this, I must have been – must still be – angry, but I wasn’t and I’m not. I just couldn’t understand – and still can’t – that someone would get on that Tube or on the bus and blow themselves up and kill other people and leave their own family, leave their wives, leave their babies too. But, while it should never have happened, this awful tragedy, I now believe that I was meant to be on that train.

This was the journey I was meant to be on. A few years after 7/7 I met a great man, Nick, and, despite not knowing if I could get pregnant because of the impact of the bomb, I’m a mum – weirdly, my son Oscar’s due date was 7 July 2009 (though he was a week late). Nick and I are no longer together, but we’re more than happy. I keep in touch with other survivors – we call it the exclusive 7/7 club, that no one wants to be a member of – and over the years I’ve had so much joy from mentoring other amputees.

Life is short, and we all need to believe in our lives, to believe we’re on the right path. We need it to be happy in this unpredictable world. It’s the only way.

The first episode of ‘7/7: The London Bombings’ airs at 9pm on 5 January on BBC Two