‘We’ll lose no sleep over this’: Liverpool comes out fighting after being stripped of world heritage status

The sense among many is that, UN-recognition or not, this is a city that prizes its past as the one-time unofficial second city of the British empire. By Colin Drury in Liverpool

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the long derelict Collingwood Dock in Liverpool, a million weeds grow through the cracked concrete ground. A handful of abandoned buildings – windowless, doorless, in one case roofless – sit sparsely by the waterside. Old mooring bollards rust unused. It is, says Sarah Doyle, the city council’s cabinet member for development, a “post-industrial ghostland”. Michal Parkinson, CBE and professor in urban studies at Liverpool University, puts it another way: “it’s a f*****g shitheap.”

Yet this week, this sprawling Victorian shipping point – unused in almost half a century – has become the Ground Zero of a decision to strip Liverpool of its much-cherished Unesco World Heritage Site status.

A £5bn plan to develop this and four other derelict docks was cited by the UN body as the main reason for removing the city from its prestigious register, which also includes the Great Wall of China and the Taj Mahal in India.

It wasn’t just that Unesco disliked the proposals for apartments, office space and retail – although they decidedly did not. More pertinently, they appear to have not wanted any significant development along this 2.8km waterfront for fear it would destroy its Victorian “integrity and authenticity”. In 2015, the body went so far as to request a moratorium on all new buildings in Liverpool until its officials in Paris could agree to a future masterplan.

“This is one of the poorest neighbourhoods, not just in England, but in Europe, and we have this site which has been withering away for decades, and now we have the opportunity to regenerate it and create jobs and opportunities for people living here,” says Doyle, stood on the dock.

“And to be asked [not to do that], it’s out of touch with reality… It’s all well and good Liverpool having this shiny badge saying we have World Heritage status but what about the people who live here? Do they not deserve a city that works for them?”

In particular, the UN took issue with the building of a new £500m stadium for Everton Football Club at Bramley-Moore Dock – a scheme which the council hopes will create 15,000 long-term jobs. “This isn’t just a stadium,” says Doyle. “It’s an economic driver. It will help lift thousands of people out of deprivation.”

The initial reaction here to Wednesday’s decision was somewhere between disappointment and fury. Steve Rotheram, metro mayor of the city region, called it a “retrograde step” taken “on the other side of the world by people who do not appear to understand” Liverpool. Joanne Anderson, the city’s directly elected mayor, said simply that Unesco had got it “wrong”. She suggested she may look for a way to appeal.

Yet today, 48 hours on, there is another feeling emerging: a sense of relief at no longer having to spend time and resources working with a body that seemed intractable, and whhich had not even visited the city since 2015.

Since Doyle herself became a cabinet member in May, she says the council has invested huge effort into trying to reach out to Unesco – “but they have just not been bothered” she adds. “So, with that perspective; yes, [it’s a relief]. It’s a fresh start.”

Key to that feeling perhaps is the sense among many that, UN-recognition or not, this is a city that prizes its past as the one-time unofficial second city of the British empire.

Development here has, inevitably, not always been to everyone’s taste. A trio of 2013 waterfront buildings have been nicknamed The Three Disgraces by some; while there is a widespread feeling that previous mayor Joe Anderson – arrested last year by police investigating corruption – was so keen to rush through new schemes that the city lost some of its unique character.

“Some parts now look the same as any other city,” says Gemma Longworth, a 37-year-old upcyclist based at the Merseymade art studios, itself a listed building dating back to the 19th century. “It has become generic.”

Yet Liverpool’s unique history as a mercantile and maritime port has never been ignored by officials here.

Some £750m has been spent on more than 100 historic assets since the city was first given heritage status in 2004, while the Merseyside Civic Society says there is now greater access to history than ever before. In 2000, 13 per cent of the city’s heritage was at risk, according to the aforementioned Professor Parkinson. Today that figure is just 2.5 per cent.

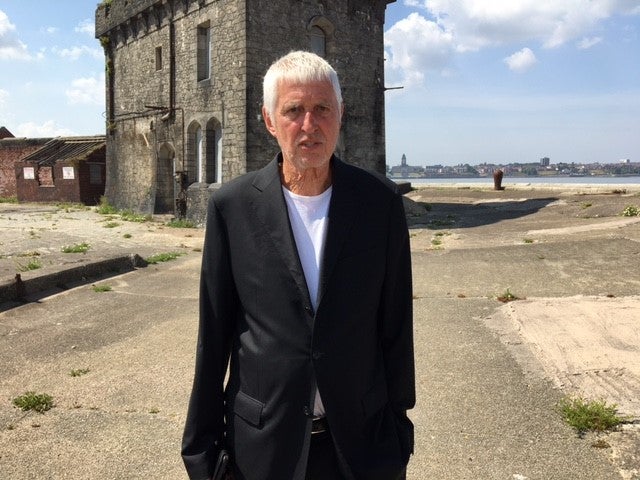

“The problem is Unesco cannot accept that big city sites cannot be museums or mausoleums,” the 74-year-old, who spent three years on the city’s Liverpool World Heritage Site Taskforce. “They have an advisory body called the International Council of Monuments and Sites, and they are basically a heritage Taliban. They cannot be appeased. We have this fantastic waterside site sat here empty with Everton asking to bring jobs and development – and invest in a range of heritage points. And there’s Unesco saying, ‘We want it left as it is.’ It just lacks common sense.”

His colleague Jonathan Tonge, a professor in politics at the university, agrees. “All Unesco has done is highlight its own irrelevance,” he says. “Liverpool will not lose any sleep over this.”

He himself regularly works in Belfast. Once or twice a year, he does the journey by ferry just so he can see the skyline. “It’s magnificent,” he says. “You cannot help but say, ‘my goodness’, when it comes into view. And the key thing is the modern buildings – I think there’s wide agreement on this – add to that.”

The fact that Liverpool has had its status revoked has been seen by some as a failure of both civic leadership and political nous

Even the region’s civic society appear baffled by the delisting. “It is a huge regret because being on that list is great company to be part of,” says chairperson Gavin Davenport. “But on balance [the Bramley-Moore development] is right. It takes us forward while actually improving access to heritage around the dock.”

Nonetheless, in a city that welcomes nine million visitors every year, there are some fears that tourism numbers could be hit by the decision.

Perhaps more pointedly, there is no real disguising that this is a humiliation. Liverpool is only the third ever site to be removed from the list – after an antelope sanctuary in Oman and the German city of Dresden (stripped of its status for building a bridge). Whatever is said here on Merseyside, the UN body does not take such action lightly. The other 31 UK sites – including Bath, Stonehenge and the Lake District – all appear to remain safe, although a report suggests planss for a tunnel under the stone circle are endangering the Wiltshire site’s status. The fact Liverpool has been sent packing is, some have suggested, a failure of both civic and governmental leadership. The campaign group Save Britain’s Heritage called it a “national embarrassment”.

It raises the question: did leaders here do enough? The fact that Joe Anderson once called World Heritage status a “certificate on the wall” suggests the answer is probably not.

”He was truculent and abrasive,” says Davenport. “And that did the city no favours because, clearly, it doesn’t win friends. I think more could have been done to reach compromise.”

Yet when the new Mayor Anderson – elected in May – wrote to Unesco effectively asking for a rapprochement and to invite them to the city, the letter went unanswered. Wednesday’s vote at a virtual conference hosted by China went ahead without anyone from the council being invited to make representations.

All of which brings us, in a roundabout fashion, to the Royal Albert Dock, about a mile-and-a-half down river from Collingwood.

At the beginning of the Eighties, this part of the waterfront also stood abandoned. The very dock itself was dry. Lads used to come here, climb down into it and play five-a-side.

Today, following 25 year of development thought to total more than £1bn, it is one of the UK’s most magnificent culture and tourism attractions, home to The Beatles Story, the Merseyside Maritime Museum and Tate Liverpool, as well as numerous bars and restaurants.

“Look around,” says Viv Phelps, a guide with the City Explorer Liverpool opentop buses which run from here. “There’s nowhere in the world like it.”

The 58-year-old herself was born and raised in the city, and, as a guide, probably knows Liverpool and its history as well as anyone. And, today, as she waves visitors onto open-top tour buses with one hand and eats an ice lolly with the other, she is decidedly nonplussed by the loss of World Heritage status.

In a touch of synchronicity, she uses a word uttered earlier at Collingwood. “Forty years ago, this [Albert Dock] was a s***heap,” the grandmother-of-three says. “Where were Unesco then? They only paid attention to us in the first place because of the work done improving this dock. Now they want to stop us doing the same somewhere else? It makes no sense. Let them take their ball home.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments