Jihadi John biographer pulls out of speaking event over 'gagging' fears

Exclusive: Robert Verkaik refused to sign the University of Westminster's 'code of practice' for external speakers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

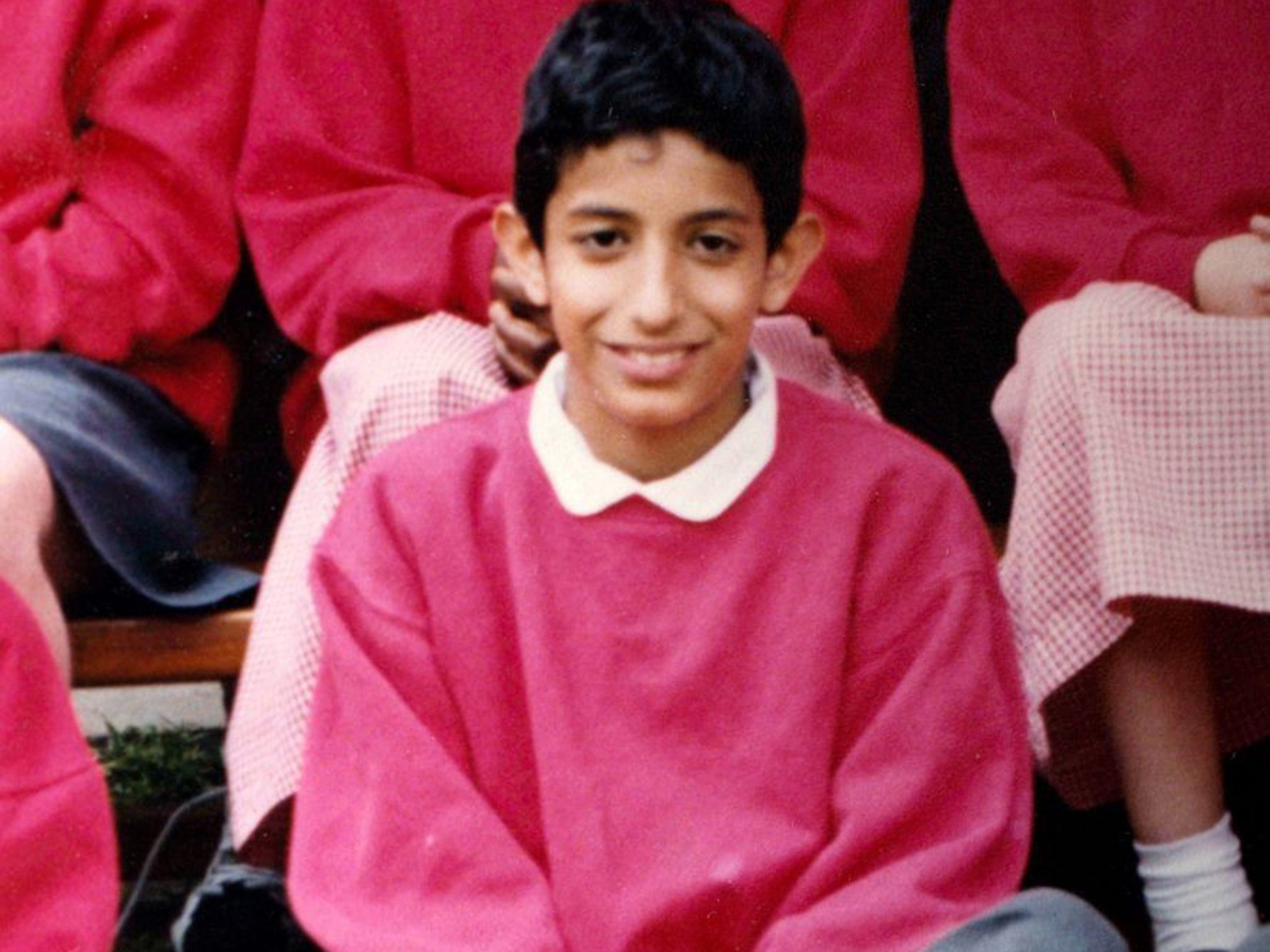

Your support makes all the difference.A writer who charted Mohammed Emwazi’s passage from misfit schoolboy to the Isis executioner known as Jihadi John has pulled out of a speaking event at the extremist’s former university, claiming that he is being gagged.

Robert Verkaik was told he could not talk unless he signed the University of Westminster’s “code of practice” for external speakers. The code is inspired by the Government’s controversial counter-radicalisation policy Prevent – the very subject he was meant to be critically debating.

Mr Verkaik refused to sign the document, for fear that it would leave him unable to raise difficult issues, such as complaints by young Muslim men that they have been radicalised because of MI5 harassment. Such opinions have previously been criticised as extremist by the authorities.

“When Islamic advocacy groups like Cage tried to argue this point, the Prime Minister called them apologists for terrorists,” said Mr Verkaik. “I don’t see how I can take part in a debate when the issues I wish to raise may end up with the university and me falling foul of counter-terrorism policy.

“It seems to me if I sign the University of Westminster guidance then I will be gagging myself,” said Mr Verkaik, a former journalist at The Independent.

The Government’s Prevent strategy sets out to stop people being drawn into terrorism. It includes warnings to institutions about the threat from speakers expressing “non-violent extremism” that could be exploited by terrorists. A university speaker’s code was introduced because of concerns that students were being exploited by hate preachers.

Mr Verkaik also expressed astonishment at being told by the university that it had a policy of not confirming that its former student Emwazi was indeed Jihadi John.

The university said in an email to the writer that it did not want to be “distracted” by the issue. The university said that inviting Mr Verkaik and other guests to discuss counter-terrorism had been a “courageous” step given the focus on the institution.

Westminster also declined to discuss the potential significance of Emwazi’s years at university in his radicalisation with Mr Verkaik while he was researching his book, saying that it would “technically” be in breach of its data protection rules, the writer said.

The university commissioned its own report into campus extremism, which reported in September that its Islamic students’ society was dominated by ultra-conservative elements who had refused to speak to female Muslim staff members. Following the identification of Emwazi, who appeared masked in Isis videos depicting the murder of Western hostages, the university cancelled a planned address by a radical preacher who had described homosexuality as a criminal act.

Index on Censorship’s chief executive Jodie Ginsberg said she was concerned that aspects of the government’s anti-extremism strategy meant that discussion of the issue was being stopped.

“Increasingly, people can’t even talk about extremism without being accused of being extremists themselves or of encouraging extremism,” she said. “That’s leading to a ridiculously high level of caution that in turn leads to censorship – in arts, in academia, and in the media.”

Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute, who has written his own book on domestic extremism, said the universities had to weigh free speech against its duty to students.

“It’s a very difficult space,” he said. “Individuals have to make their own decisions about this. But part of the issue is that it hasn’t always been clearly indicated by Government who it is that schools are meant to be keeping out.”

A University of Westminster spokesperson said that no other speakers had declined to sign the code before speaking.

“We are working hard to counter any form of extremist narrative through the Prevent duty, but we are also striving to maintain freedom of speech and open dialogue with events and debates that demonstrate a balanced approach, however challenging that may be.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments