I helped expose the extent of the infected blood scandal – this does not end here

Having investigated the scandal over a number of years for her award-winning podcast and book, Cara McGoogan recounts the relief of an emotional week and why it isn’t over yet...

When I attended the opening of the Infected Blood Inquiry at the end of April 2019, I’m ashamed to say I knew very little of the scandal which has now killed some 3,000 people. I heard shocking stories of people who had contracted HIV and hepatitis from medical treatments decades earlier, who had lost loved ones, and been robbed of the chance to have children or careers.

They spoke of children with haemophilia being used as human lab rats at a specialist boarding school and of being cruelly dismissed by institutions that should have helped them. They argued there had been a cover-up from the government and NHS spanning 35 years.

To my naive ears, it sounded almost implausible and, in recent weeks, I have seen this reaction reflected as people took in the findings to people ahead of the inquiry’s final report.

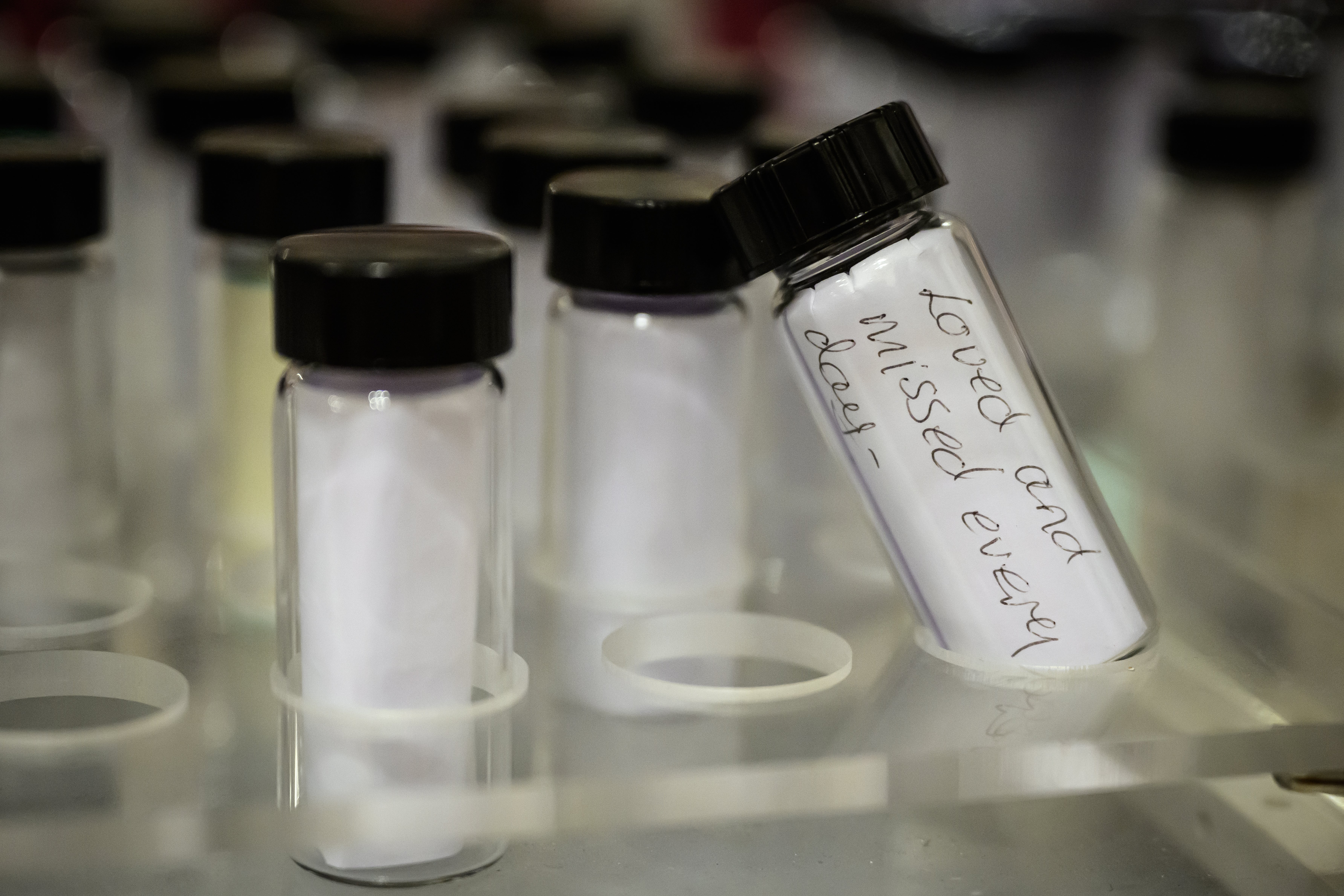

But these are facts. As we now know as many as 1,250 people received HIV and up to 5,000 more hepatitis C from a “wonder drug” for haemophilia called Factor VIII made from high-risk human plasma that should never have been licensed for import from the US, according to the findings. The infections of a total of 30,000 people with life-threatening viruses from blood products and transfusions were “no accident”.

In the last five years, I have investigated the story of Factor VIII for a book, The Poison Line: Life and Death in the Infected Blood Scandal, and an award-winning documentary podcast, Bed of Lies. I have combed through thousands of pages of witness testimony and historical documentation, and spoken to survivors, bereaved family members, doctors, lawyers, politicians, and whistleblowers.

This story is a catalogue of heartbreak – and it’s a scandal. It doesn’t amount to just a “day of shame” as the papers said on Tuesday, but half a century of shame.

Within a mountain of evidence, I’ve seen proof that children were experimented on without their knowledge; pharmaceutical companies knowingly sold a treatment that could transmit HIV and hepatitis; and the Department of Health shredded documents to cover up the truth.

Given this, it was both historic and emotional to sit alongside so many of those affected and hear Sir Brian Langstaff, chair of the inquiry, conclude, “The infections happened because those in authority – doctors, the blood services, and successive governments did not put patients first.”

For me, the most heart-wrenching moment was when Sir Brian addressed over 1,000 people in the Central Hall in Westminster and asked them to imagine if three-quarters of people in the room died; this is the number of those with haemophilia who have been lost to Aids-related illness.

The more I have learned about the infected blood scandal, the worse it gets. And I believe there is more to come.

In the opening week of the inquiry, I conducted two interviews. The first was with a survivor who had to go to a hospital appointment right after giving evidence. The other, with a lawyer representing over 1,000 clients who had sued the Department of Health for misfeasance in public office – an act that helped trigger the inquiry.

Since then, I have gotten to know former pupils from Treloar’s school, a specialist boarding school for children with physical disabilities. Of 122 children with haemophilia who went there, 80 have died after contracting HIV, hepatitis and other viruses from medical treatment. Ade Goodyear told me how, when he was a teenager, he was pulled into the doctor’s office with a group of friends and given a devastating diagnosis.

The doctor went around the room and one by one said: “You have, you haven’t, you have, you haven’t, you have, got HTLV-III” (as HIV was initially known).

Learning he had two to three years to live. Outside, Ade’s friend Dave shouted, “We’re dead, we’re all f***ing dead.” And with that Ade and his friend were sent back to class.

Nearly 40 years on, it was a joy to yesterday hear Ade say his head would finally rest lightly on his pillow this week, knowing he had achieved a promise to the friends he lost: to get justice for them all. “We did it,” he said gleefully to another former pupil outside Central Hall.

Another story I will never forget is that of Frankie, who contracted HIV from her husband Joe when she was in her twenties. Newly married in 1985 when she was just 19, the couple soon received the devastating news that Joe had Aids and would live just a few more years. At the time, Frankie was pregnant.

What should have been happy news became a living nightmare. Very little was known then about HIV and how it spread between partners – and to unborn children. Amid the confusion, Frankie felt pressured by doctors into having a termination. By the time the decision was made, she was seven months into her pregnancy.

The procedure was utterly horrendous. Medical staff wore protective uniforms that covered their faces and Joe was made to wait outside of the room, so when Frankie was fighting the pain of contractions she had no one’s hand to hold. After it was over a doctor said to her: “Women like you should be sterilised.”

To this day, Frankie has been left feeling like she’s a murderer.

But some of the guilt and pain she has lived with was lifted on Monday when she saw her story documented in Sir Brian’s report, alongside all the other women who had been forced into having terminations after their husbands with haemophilia tested positive for HIV. One woman was sterilised.

Frankie had a smile on her face and an easiness about her as she told me on Monday, “It’s like the air is being released,” she says.

This is a story of personal tragedy, but also international deception, greed, negligence and wrongdoing.

Through my reporting, I met American lawyers Tom and Lorraine Mull, an incredible husband and wife duo who fought the pharmaceutical companies that made Factor VIII for a decade.

Tom discovered a notorious prison in Louisiana, which sits on a piece of land the size of Manhattan and holds some five thousand prisoners, had a plasma centre within its walls that was pretty much staffed by inmates.

Speaking to some of those who had given and taken plasma, he learned there were very few safety measures. Prisoners could have sex with one another, show signs of intravenous drug use, and even have had a positive hepatitis B test, and still donate plasma. For each donation, which they could do twice a week, they earned $15.

This plasma was mixed with tens of thousands of donations from other high-risk sources and used to make Factor VIII. Just one donor needed to have a blood-borne virus for the whole batch to be contaminated.

Tom and Lorraine shared all the documents from their trial with me and I was able to see how they took four companies to court and after a decade of fighting won a jury verdict of fraud against two companies, Bayer and Alpha, and a $100m settlement for 124 clients from those businesses. Baxter and Armour were also made to pay out.

On the witness stand, a leading American doctor admitted it was “highly likely” every bottle of Factor VIII manufactured in the US in 1983 had been contaminated with HIV and hepatitis. But the companies who made it had continued to pump it out regardless.

“A medically necessary product, sourced by cheap labour, manufactured with an economy of scale, a permanent captive audience, governmental acquiescence and cooperation,” said Tom.

His legal colleague Michael Baum said, “It was as if all these haemophiliac kids and adults who were depending on Factor VIII were sharing needles with intravenous drug users and prisoners during one of the worst epidemics of blood-borne diseases in history.”

Knowing about the risk of blood-borne viruses in US plasma, Sir Brian concluded the Committee on Safety of Medicines – which had been established after the Thalidomide disaster – should never have licensed Factor VIII from US companies. The Department of Health failed NHS patients by not questioning the decision as the dangers became more apparent.

A question remains this week of whether there will be any repercussions for the regulator, the Department of Health, and the pharma companies who made and sold a deadly treatment to the NHS.

In the US these four companies settled $660m with people infected with HIV, amounting to $100,000 each. In Germany and Japan, pharma companies were forced to contribute a significant proportion of money to the compensation pot.

There are campaigners who are agitating for criminal charges, following the example of France and Japan, where doctors, pharma executives and government ministers stood trial, some of whom served short prison sentences. Margaret Thatcher and Ken Clarke were unwilling to compensate victims because they didn't want to introduce what they saw as an American legal culture into the UK. And so our institutions chose to 'close ranks around a lie', to use Jeremy Hunt's description. With so many years having passed it could be difficult to achieve convictions here, not least because many of those who made decisions have now died.

From thalidomide to infected blood to the maternity scandal that is currently unfolding, we can see similar patterns of hospitals being underfunded, patients left in the dark, and a lack of transparency when things go wrong.

Sir Brian has outlined recommendations for improvement, including a nationwide duty of candour for when things go wrong and an end to a “culture of defensiveness”. Every healthcare professional should know the details of the infected blood scandal; it should be taught in medical schools across the country. And every hospital should strive to never let this happen again.

The most important thing is that we see the government make good on its promise to compensate people for half a century of trauma and that it does so swiftly and comprehensively. The last thing we should want as a country is for these survivors and bereaved relatives to have to spend another day of their lives campaigning.

For me, the overwhelming takeaway is the 2,500 words written by Sir Brian and his team which outline a slew of failures over 50 years that have made victims feel heard after a lifetime of institutional gaslighting.

At the end of his court case against the pharma companies, lawyer Tom Mull reflected on the bittersweet conclusion. He had helped prove how sick the system was: those who needed Factor VIII’s life-changing properties were caught in a deadly confluence of opportunity and greed. But at least people would now know the truth. And that, for him, was the most important thing.

The Poison Line: Life and Death in the Infected Blood Scandal by Cara McGoogan is out now (Penguin)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments