‘All that is missing is a whip’: How Home Office ignored migrant worker abuses on farms

Foreign workers on British farms suffered racism, wage theft, threats and appalling conditions, according to evidence heard by inspectors — but nothing was done. Emiliano Mellino and Matthew Chapman tell the whole story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They travelled thousands of miles to come to the UK, lured by the prospect of work and decent wages.

But new evidence uncovered in an investigation by The Bureau for Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) and The Independent suggests people who came to Britain to fill gaps in the UK’s agricultural workforce faced far greater levels of exploitation than previously thought.

From threats and wage theft, to racism and appalling conditions, inspectors heard hundreds of shocking allegations of what was happening to seasonal workers employed across UK farms. And nothing was done.

The investigation reveals that the Home Office knew about the allegations, failed to act on them and then attempted to stop that information from being made public. Plus, the government could be in breach of its obligations when it comes to the prevention of modern slavery.

Revealing the extent of abuse

Following a five-month freedom of information battle, TBIJ was given access to 19 farm inspection reports produced by the Home Office between 2021 and 2022. The documents summarise interviews and findings of inspectors who visited farms employing people on the seasonal worker visa.

Nearly half (44 per cent) of the 845 workers interviewed as part of the inspections raised welfare issues including racism, wage theft and threats of being sent back home. On most of the inspected farms, there were allegations of mistreatment or discrimination and more than 80 per cent of workers interviewed on the three most-complained-about farms raised an issue of some sort.

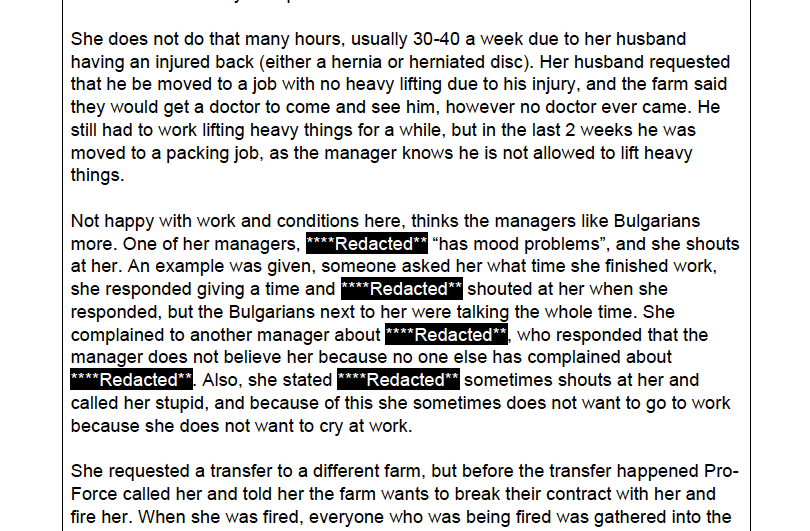

One Ukrainian woman told inspectors she was confined to her caravan without access to medical assistance or food for 11 days when she caught Covid. She said she was “starving” and was not provided with any support by her scheme operator, one of the small number of recruitment companies authorised by the government to arrange seasonal worker visas. Another person reported that a colleague was denied dental care, leading to them pulling out their own tooth.

At another farm, where more than a dozen people complained about being mistreated, a manager was reported to have shouted: “I am a pure-blooded English woman, I will stay to live here and you will go back to your poor countries.”

The findings also reveal unlawful recruitment fees are more common than previously thought, with workers from six countries saying they had paid recruiters as much as £7,500 for jobs in the UK. The charging of these fees is illegal in the UK.

‘State-sponsored exploitation’

The reports contradict claims by government ministers and visa scheme operators about the treatment of seasonal workers on British farms.

Two visa scheme operators previously told the House of Lords that only 1 per cent of their workers had made complaints, and last month, farming minister Mark Spencer claimed people on the scheme are “very well looked after” and that employers “make sure that their welfare needs are met”.

But none of the allegations raised during these inspections was investigated by the Home Office or visa scheme operators, according to a report by the independent chief inspector of borders and immigration.

The visa scheme operators are required to ensure participants are properly paid, treated fairly and live in hygienic accommodation. Despite the numerous issues raised with the inspectors, no government-licensed scheme operator has lost its licence or been sanctioned for failing to meet these standards. Some have, however, been penalised when workers stayed in the UK beyond the end of their visas.

“I think it’s very troubling that [the government] is more concerned about whether people have left the country rather than were they treated properly, fairly and with the dignity that they deserve,” said Sara Thornton, the government’s former independent anti-slavery commissioner (IASC).

Following a government report stating that the 2019 pilot of the visa scheme uncovered “unacceptable” conditions, Thornton wrote to ministers with concerns about the risks faced by workers. She recommended reforms such as compensation for those who had paid illegal recruitment fees and a means to resolve disputes run by independent third parties. The recommendations were not implemented, and following Thornton’s departure the IASC post was left vacant for more than year until a replacement was appointed earlier this month, despite its occupancy being a legal requirement.

Instead, under pressure from the National Farmers’ Union, an industry association representing farm owners, the government rapidly expanded the seasonal worker visa scheme from 2,500 workers in 2019 to as many as 55,000 this year. Simultaneously, the Home Office increased the visa fee by £50 to £298 – more than twice what it costs to process it.

“With the knowledge of [the content of the reports], you’d think that it would have slowed the government down actually, but it hasn’t,” said Jamila Duncan-Bosu, a solicitor with the Anti-Trafficking and Labour Exploitation Unit, a charity bringing claims on behalf of modern slavery victims.

Failing to investigate the abuses highlighted in the reports could mean the government has breached its obligations to prevent forced labour under the European Convention on Human Rights, she said. “Essentially, it is state-sponsored exploitation,” she added.

‘Critical enabler’ of the agriculture industry

The Home Office refused several of TBIJ’s requests for the inspection reports, until an appeal was lodged with the Information Commissioner’s Office, which regulates data privacy and freedom of information requests. The reports were eventually released, albeit with the farm names redacted.

When refusing to release the reports, the Home Office argued that it was a “critical enabler of the agriculture industry” and revealing the names “would likely discourage workers from these farms”.

“We have transparency in supply chain legislation, which applies to businesses, but it seems that the Home Office don’t hold themselves to the same standards when it applies to schemes that they’re running,” Thornton said.

In response to TBIJ’s findings the Home Office said that “each year improvements have been made to stop exploitation and clamp down on poor working conditions”.

It added that a new team had been established to safeguard worker rights by “improving training and processes for compliance inspectors and creating clear published guidance for robust action for scheme operators where workers are at risk of exploitation”.

It is understood that the team has just half a dozen staff. To put that figure into context, there are hundreds of farms in the UK taking seasonal workers.

At the same time, the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA), the government body in charge of licensing labour providers and tackling exploitation in the agriculture sector, has had to consider job cuts after the Home Office slashed £1m from its £7m funding.

‘All that is missing is a whip’

Meanwhile, unpaid hours are common, according to the Home Office reports. In nearly two thirds (12 out of 19) of farms inspected in 2021 and 2022, workers said they were not always paid for the hours they worked, were off sick or travelled, or they faced deductions beyond the maximum allowed by law. One farm had been reported by HMRC to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy for failing to pay the minimum wage.

In most farm inspection reports, people said they had been mistreated. That included bullying, being publicly humiliated by supervisors and racism. When workers made complaints, some were ignored or told they could leave the farm and go back to their home countries.

“Employers treat you like s***! Always picking on you and give you extra jobs when you are already busy. There is racism,” a worker from Barbados was quoted as saying.

People were also made to work 12-hour days or back-to-back for up to two weeks, and without having agreed to do so, according to one Home Office inspector. When they told their managers they needed a day off, the response was: “You have come here to work, so you have to work,” the official wrote.

A Moldovan worker cited in the same report began to cry when she explained she only got one 15-minute break and was prevented from taking another one, even to go to the toilet, drink water or eat, until she hit her targets.

“All that is missing is a whip to beat people,” she said.

Mice, cockroaches and bed bugs

The Home Office reports echo a TBIJ investigation that found widespread mistreatment of migrant workers in more than 20 farms, nurseries and packhouses across the UK in 2022.

People reported that living conditions were unsafe and unsanitary, despite paying farmers as much as £2,000 a month for rent between six people.

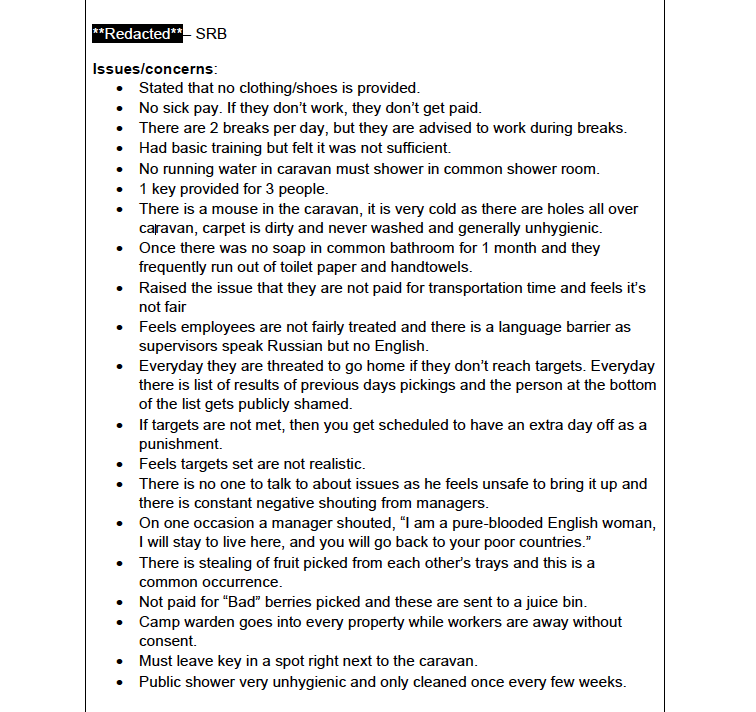

A TBIJ analysis of the inspection reports reveals accommodation problems are the most common complaints from people on the scheme, with nearly a quarter raising issues with compliance officers.

On many farms, people did not have showers or toilets in their caravans. In others, there were mice, cockroaches or bed bugs. Some people said they had to share a bed with a stranger or were forced to live in cramped spaces that were often cold or mouldy.

A pregnant woman from Barbados was made to sleep in a child’s bunk bed while working on one farm. She didn’t have en suite washing facilities, so had to walk to a communal bathroom, sometimes in the rain.

There were also complaints about privacy and safety. In several farms, managers or admin staff would enter caravans unannounced or without permission, and in others, workers had to share one key among as many as six people. In the worst of cases, there was no lock at all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments