‘Supernatural’ Bronze Age find could shed light on one of London’s greatest prehistoric mysteries

How archaeology is revealing the long-lost secrets of Old Father Thames

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Archaeological research may be about to shed remarkable new light on one of London’s greatest prehistoric mysteries – the ancient religious status of the River Thames.

It’s known that Bronze Age and Iron Age Britons deposited thousands of prehistoric objects in the river as gifts to its deity or spirits.

But now, archaeologists investigating a site in east London have discovered what may be a 9th-century BC Bronze Age temple or ceremonial centre established specifically to honour or venerate the Thames as the physical incarnation of such divinity.

What’s more, the archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of beautiful bronze artefacts which Bronze Age people had buried in the complex – potentially as votive offerings to that supernatural being.

Archaeologists say the discovery is of “substantial international importance”.

“Our investigation will tell us much about Bronze Age metalworking technology, how the bronze artefacts were used – and their potential role in the belief systems of that time,” said archaeologist Andy Peachey, a prehistorian from Archaeological Solutions, the specialist unit which carried out the excavation.

It’s the largest ever Bronze Age hoard to be discovered in London, and one of the three largest ever found in the UK.

The site, near Rainham in the London Borough of Havering, directly overlooks what would have been a large area of of frequently flooded Thames-side marshland.

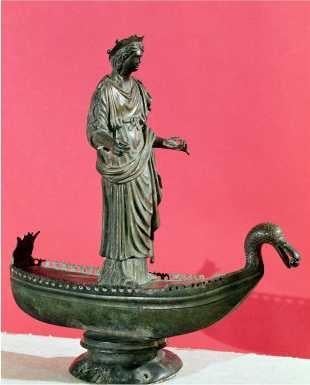

The find is particularly significant because of the known ancient tradition of worshipping rivers as sacred. That tradition was strong throughout much of Britain and continental Europe, and parts of western and southern Asia.

On the whole, with relatively few exceptions, river deities tended to be female.

There are literally thousands of rivers in Europe and Asia associated with known and named ancient deities – including Sequana (the Seine), Sionann (the Shannon), Verbeia (the Wharf), Durius (the Douro in Portugal), Alpheus (River Alfeios in Greece), Tiberinus (the Tiber in Italy), and Ganga (the Ganges in India).

In dozens of cases the mythological narrative, revealing a river’s divine status, has survived across the millennia.

The similarity of some of those narratives – from places as far apart as Ireland and India – strongly suggests that they are of very great antiquity, going back several thousand years.

Among the most common narratives are, for instance, ones that describe how a goddess argued with or challenged another deity or spirit, who then turned her into a river – or merged her with an existing one by drowning her.

Other frequent mythological motifs explaining river creation involve, for example, deities turning themselves into rivers in heaven and then sacrificing themselves by falling to Earth to nourish, sanctify or redeem humanity or a specific people.

The newly discovered Rainham site is the first potentially ritual or ceremonial prehistoric complex of this sort in the lower Thames valley to be fully investigated by archaeologists.

Detailed excavation has revealed it to have been a large 60m-square ditched and banked enclosure, located at the end of a promontory protruding into one of the Thames Valley’s largest ancient marshland areas.

In the centre of the enclosure was a six-meter-diameter circular building with what was probably a substantial north-facing square porch, facing the enclosure’s entranceway.

But it was behind the building, in the enclosure’s southern ditch, overlooking the marsh (and, beyond that, the Thames itself) that the archaeologists made their most significant find – four pits (each originally around a metre deep) in which 453 pieces of often very fine metalwork had been buried (probably originally in textile or basketwork bags).

Significantly, most of the items had been deliberately broken (a common phenomenon in prehistoric ritual deposits).

In total, the archaeologists recovered 38 sword fragments (from well over a dozen weapons), 146 pieces of bronze axes and around 40 fragments of daggers, razors and spearheads, along with more than 100 fragments of bronze ingots and other metal objects. In aggregate, the artefacts weighed 45 kilos and represented around 300 originally complete objects.

The excavation also revealed three other pits – containing hundreds of fragments of broken pottery (potentially general refuse – or even the debris from small-scale ceremonial feasting).

Significantly, two other hoards of metalwork are known from the area, discovered just a few miles away back in the 1950s and the 1960s.

The precise location and nature of the site itself (at the end of a promontory and immediately adjacent to and facing directly onto one of the Thames Valley’s largest wetlands) suggests a potential ritual or ceremonial function, rather than a purely commercial one.

Intriguingly, the circular building’s entranceway faces north, which is not the norm for ordinary residential roundhouses.

However, in most other cases of marshland-related metalwork deposits, the prehistoric rituals involved placing bronze artefacts in (or throwing them into) rivers and swamps, rather than merely burying them immediately adjacent to a wetland.

Although a prehistoric commercial function cannot be completely ruled out, it is conceivable that the artefacts may have been held in storage within the complex, awaiting eventual ritual deposition in the adjacent swamp. Indeed, it is possible that burying it within a sacred enclosure would have been seen as giving the items sacred status, if the intention was to later deposit them in the adjacent marsh.

However, the bronzes were all deposited in the pits at virtually the same time – but at the very end of the lifetime of the complex. It is therefore also possible that they were interred as an act of ritual closure – marking the sanctified decommissioning of this probably sacred site overlooking the Thames-side marshes.

If indeed the complex was a ritual or ceremonial centre involved in the veneration of water spirits – or of a river deity – it will raise the question as to the potential identity of a prehistoric Thames god or goddess.

Although there are at least half a dozen Roman and Romano Celtic temples (all dating from at least 900 years after the Rainham complex), none of them give any clue as to what the name of such an ancient Thames deity might have been.

Since at least the 18th century, Old Father Thames has been a popular literary and artistic motif – but he is probably a romantic early modern invention.

Any truly ancient Thames deity would almost certainly have been female (like other British, Irish and French examples).

Certainly, votive offerings have been deposited in the Thames for the past 5,500 years. The oldest known name for London’s river is the Tamessa (Tamesis in Latin).

However, that name was almost certainly originally pre-Celtic – and potentially even pre-Indo-European. It seems to be linked with an Old European word meaning ‘to flow’.

So it can potentially just be translated as “the flowing one” – ie simply “The River”. Sadly, its more specific original name (if it ever had one) is lost, submerged at some point far back in the stream of time.

Commenting on the discovery of the Rainham Bronze Age metalwork, Roy Stephenson, historic environment lead at the Museum of London, said: “It’s incredibly rare to have uncovered a hoard of this size on one site”.

Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England, said: “This extraordinary discovery adds immensely to our understanding of Bronze Age life.”

The bronzes will go on display for the first time as the focal point of a major exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands in April 2020.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments