Grenfell Tower fire inquiry: What are the key findings of the report?

There was ‘systematic dishonesty’ in product testing and marketing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s final report makes damning conclusions about how the block of flats in west London came to be in the condition which saw fire spread dramatically in June 2017 to claim the lives of 72 people.

A government drive for deregulation meant concerns about the safety of life were “ignored, delayed or disregarded” in the years before the Grenfell Tower fire, the inquiry into the disaster has found.

In its final report, published on Wednesday, the seven-year inquiry said civil servants had felt unable to raise concerns about fire safety due to a focus on deregulation, and accused ministers and senior officials of a “serious failure of leadership” in allowing such a culture to develop.

But the inquiry – led by retired judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick – went further, saying the government had “failed to discharge” its responsibilities to ensure public safety for more than 25 years after a major fire in 1991 at Knowsley Heights, Merseyside.

Here is a summary of the report’s main findings:

– The government ignored warnings

For almost three decades before the fire the government had “many opportunities” to identify the risks posed especially to high-rise budlings by flammable cladding and insulation, the report said.

By 2016, the year before the fire, it was “well aware of those risks, but failed to act on what it knew”.

After the Lakanal House fire in Camberwell, south London, in July 2009, in which six people died, the coroner’s recommendations were “not treated with any sense of urgency” and “legitimate concerns” were “repeatedly met with a defensive and dismissive attitude by officials and some ministers”.

– A ‘deregulatory agenda’ within government saw safety matters ‘ignored, delayed or disregarded’

Following the Lakanal House fire, the government had a “deregulatory agenda, enthusiastically supported by some junior ministers and the secretary of state”, which “dominated the department’s thinking to such an extent that even matters affecting the safety of life were ignored, delayed or disregarded”.

– There was ‘systematic dishonesty’ in product testing and marketing

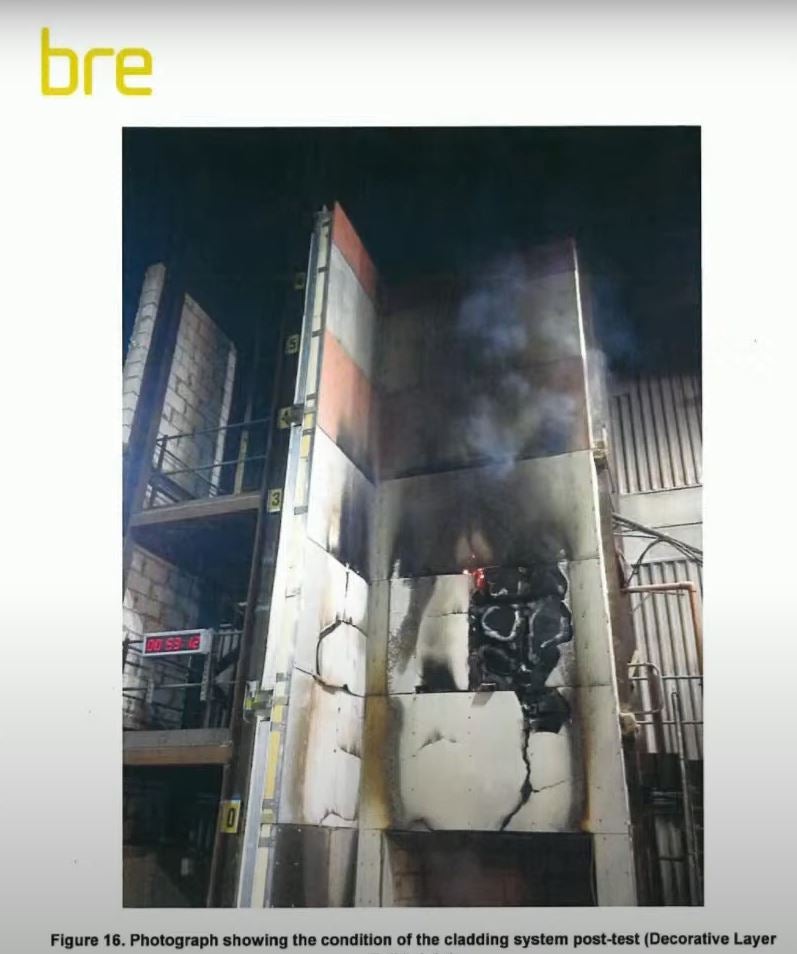

Grenfell Tower came to be wrapped in flammable material because of “systematic dishonesty” among those who made and sold cladding panels and insulation products.

These firms “engaged in deliberate and sustained strategies to manipulate the testing processes, misrepresent test data and mislead the market”.

A former government agency, the Building Research Establishment (BRE), which provided advice on building and fire safety was “complicit in that strategy” when it came to the main insulation product from Celotex.

The BRE was privatised in 1997, but years before that “much of the work it carried out in relation to testing the fire safety of external walls was marred by unprofessional conduct, inadequate practices, a lack of effective oversight, poor reporting and a lack of scientific rigour.”

Its systems were concluded not to have been “robust enough to ensure complete independence” and it was judged to have played “an important part in enabling Celotex and Kingspan to market their products” for use in the external walls of high-rise buildings.

The certification bodies, the British Board of Agrement (BBA) and the Local Authority Building Control (LABC), “failed to ensure that the statements in their product certificates were accurate and based on test evidence”, while the UKAS, which is responsible for oversight of certification bodies, “failed to apply proper standards of monitoring and supervision”.

– Statutory guidance on fire tests was ‘fundamentally defective’

Statutory guidance on complying with a requirement under the Building Regulations requiring the external walls of a building to “adequately resist the spread of fire over the walls and from one building to another” was concluded to be “fundamentally defective”.

The use of Class 0, meaning “limited combustibility”, as a standard of fire performance for products to be used on the outside walls of tall buildings was “wholly inappropriate” as neither of the main British Standard tests reflected the development of a fire on the outside of a building or gave the information needed to assess how an external wall incorporating the product would perform in a fire.

– Managing fire safety was seen as ‘an inconvenience’ by the tower’s landlords

There was a “persistent indifference to fire safety, particularly the safety of vulnerable people” between 2009 and the time of the fire.

The council – the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) and the landlord organisation – the Tenant Management Organisation (TMO) were jointly responsible for the management of fire safety at the tower.

But the demands of doing so “were viewed by the TMO as an inconvenience rather than an essential aspect of its duty to manage its property carefully”.

In turn, RBKC’s oversight of the TMO’s performance was “weak and fire safety was not subject to any key performance indicator”.

– Unedifying ‘merry-go-round of buck-passing’ on the refurbishment

There was a “serious lack of competence” and in some cases “outright dishonesty” when it came to the tower’s 2015-2016 refurbishment.

The report said: “Regrettably, the Grenfell Tower refurbishment was marked by a serious lack of competence on the part of many of those engaged on it and, in the case of some manufacturers of construction products, outright dishonesty.”

The failure to establish clearly who was responsible for what, including for ensuring designs were compliant with statutory requirements, resulted in an “unedifying ‘merry-go-round of buck-passing’ in which the construction professionals all pointed the finger at each other as being the person whose responsibility it was to make one or other of the critical decisions”.

– London Fire Brigade had a ‘chronic lack of effective management and leadership’

The fire service did not fail to understand the lessons of the Lakanal House fire – in fact its response “showed that it understood its significance immediately”, the report said.

But its failure “lay in its inability to implement any effective response”.

This failure had “many causes”, including a “chronic lack of effective leadership”, combined with “undue emphasis on process and a culture of complacency”.

Senior managers at the LFB failed to take steps to ensure that its arrangements for handling fire survival calls reflected national guidance, while senior officers were complacent about the operational efficiency of the brigade and lacked the management skills to recognise the problems or the will to correct them.

– Residents were left feeling ‘abandoned’ and ‘utterly helpless’ in the immediate aftermath of the fire

The response of government and RKBC in the first week was described by the inquiry as “muddled, slow, indecisive and piecemeal”.

It concluded the council should have done more and that some aspects of the response “demonstrated a marked lack of respect for human decency and dignity and left many of those immediately affected feeling abandoned by authority and utterly helpless”.

The local authority had no effective plan and had not trained staff adequately to deal with such an incident but, the report noted, “none of that was due to any lack of financial resources”.

It credited members of the local community for their help in the immediate aftermath, which “only emphasised the inadequacies of the official response”.

– Findings about cause of death

Inquiry chairman Sir Martin Moore-Bick made findings about the cause of death, in an effort to assist the coroner as well as “sparing the relatives of those who died the stress of prolonged proceedings”.

“In light of the expert evidence we are able to make findings about the cause of death, including findings that all those whose bodies were destroyed by the fire were dead or unconscious when the fire reached them,” the report stated.