Forget French and Mandarin - Arabic is the language to learn

With more than 300 million people speaking it, no wonder the British Council is promoting its teaching in schools

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

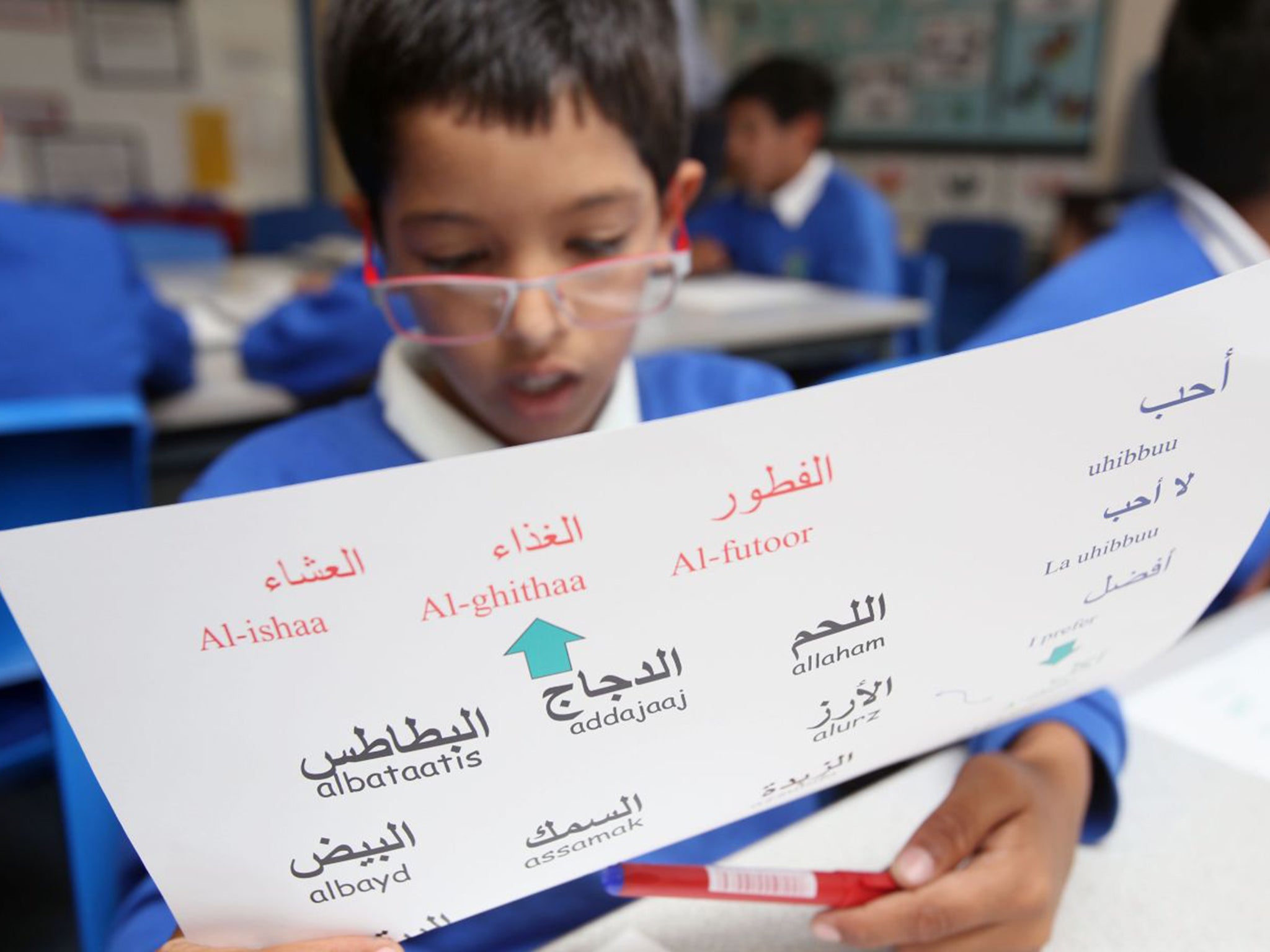

Your support makes all the difference.The 10-year-old was looking at the card in front of him which showed an image of a fish. “Samak,” he said decisively.

He and his classmates at Horton Park primary school, in Bradford, have been learning Arabic for three years now, courtesy of a drive by the British Council to boost the take-up of the language in state schools.

His teacher, Saleh Patel – one of the few Arabic teachers working full-time in a British primary school - had told the class to link the pictures on the cards with the correct word in Arabic to describe them.

Later in the lesson they were set the task of writing a sentence in Arabic. “I find it difficult,” said another 10-year-old, “but I try my hardest.” (Arabic is written from right to left – try doing that in English and you will understand how hard it can be.) There is, though, an enormous sense of enthusiasm in the classroom as the pupils try to master the language.

The project is one of eight initiated by the British Council, which was spurred by its research that rated Arabic as the second most important language for workers of the future (Spanish was rated the most important).

The study took into account Britain’s export links, government trade priorities, diplomatic and security priorities and the most popular holiday destinations.

“There are more than 300 million Arabic speakers across the world – in the Middle East and North Africa,” said Faraan Sayed, who has been working on the programme for the British Council.

In eight clusters of schools around the country 1,000 pupils study Arabic as part of the curriculum while a further 500 are learning the subject in lunchtime and after-school clubs. These are in Belfast, Sheffield, Manchester, London (where there are two), Barnstaple in Devon, Blackburn and Bradford.

In Manchester, the independent Manchester Grammar School asked some of its Syrian pupils to help with the recruitment of an Arabic teacher. They recruited an Iraqi-born teacher with the result that the school’s development plan now has Arabic GCSE provision planned from 2016.

The drive to teach Arabic will be stepped up when the British Council sends out a “language and culture” pack to around 5,000 primary schools in September, in an attempt to persuade them to take up the subject – and give their pupils an insight into the culture of the Arabic world.

Back to Horton Park, though. The school has around 400 pupils – having almost doubled in size since Sarah Dawson took over as head-teacher 19 years ago. Between them, the children speak 36 languages at home.

If the education system has been criticised in some areas for tolerating the segregation of pupils into different racial and religious groups, Horton Park is an exception. Recently it has seen an influx of pupils from Eastern Europe.

“We’ve been expanding every year,” said Mrs Dawson. “We seem to get a few pupils from everywhere.” The school serves the Canterbury Estate in Bradford – ranked as the most disadvantaged area of the city.

Mr Patel reckons the school splits about 50/50 between those who have come into contact with the language beforehand and those who are newcomers –many pupils will have come into contact with Arabic through learning the Koran in their home environment. However, they will not have come into contact with everyday Arabic phrases.

One of the problems in the future may be the lack of opportunity for the pupils to continue their studies at secondary school, as there are few that offer Arabic.

However, Mrs Dawson believes the experience of learning a second language will stand them in good stead if they have to opt for a third language in secondary school.

She also believes it is helpful to the Eastern European pupils who have arrived – as they learn English at the same time as tackling another language.

There may be little provision at the moment in the city’s secondary schools, but Mr Patel is deputy principal at a supplementary school in Bradford offering Arabic to around 900 young people – taking them up to the age of 25.

The school is developing links with a sister school in Qatar as a result of one of its teachers taking up a two-year teaching post there, giving pupils the chance to talk to their Arabic counterparts on Skype.

Meanwhile, back in the classroom, the pupils have been asked by their teacher to rate their once a week 45-minute Arabic lesson.

The consensus seems to be that it has been hard work, but they have enjoyed it.

Top ten tongues

The top 10 languages for the future, according to a British Council report, are predicted as being: 1 Spanish, 2 Arabic, 3 French, 4 Mandarin Chinese, 5 German, 6 Portuguese, 7 Italian, 8 Russian, 9 Turkish, 10 Japanese.

French has consistently dominated the language scene in UK schools, showing the greatest take-up at GCSE and A level. The biggest loser after Labour’s decision in 2004 to remove languages as compulsory for 14 to 16-year-olds, was German, which was in second place in the nation’s schools up until 2006, when it was overtaken by Spanish. Spanish is now offered at degree level by more than 70 universities – compared with 60 offering German.

The spotlight was thrown on Mandarin as the language of the future in 2010, when the schools secretary, Ed Balls, said that he wanted at least one school in every area to offer it as a subject at secondary level.

Meanwhile Arabic has risen steadily in popularity, with GCSE take-up increasing by 82 per cent between 2002 and 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments