First World War centenary: When the Albert Hall went to war

A quarter of its staff enlisted to fight, but there was also important work to be done by the rest...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Frank Snow left his day job and prepared to fight in Flanders Fields, his colleagues at the Royal Albert Hall were naturally worried that they might never see him again. Frank promised those who remained in London that he would keep in touch – and he kept his word.

A picture postcard from September 1915 shows the young soldier standing bolt upright at his training camp in his army fatigues, rifle propped up on his left soldier. "Just to let you know, as promised, I'm still at the same address, [photo] taken while at camps," Frank wrote. He signed off: "Thanking you."

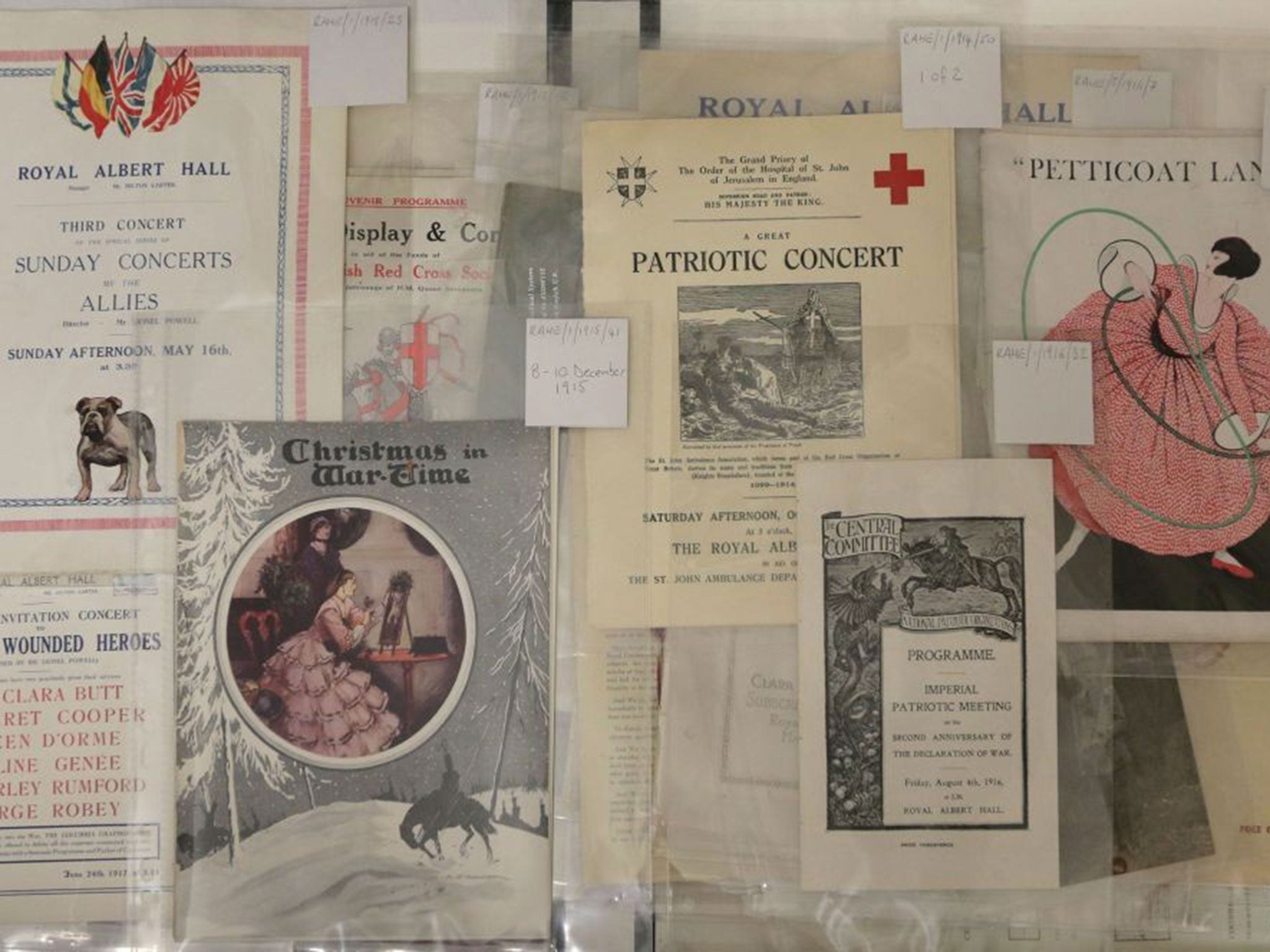

His picture is just one item, from tens of thousands in the Royal Albert Hall's archives, that has been dusted off and will be on display for the first time tomorrow. The concert hall is holding a one-off event to celebrate its unique heritage and the 40 staff who worked there a century ago. The World War One Centenary Talk – Royal Albert Hall Memories includes programmes, photographs and other documents detailing how staff kept concerts, political events, debates and other rallies going during the troubled times.

Frank, probably an administrative clerk, was one of 10 staff who fought in the war. There is no record of whether he came home but the hall's archivists, Liz Harper and Suzanne Keyte, who have been researching and planning the event, believe that he did.

"Record keeping wasn't so good back then, but we presume that Frank lived through the war as we couldn't find any trace of his name among the Commonwealth War Graves Commission," Ms Harper said. "Frank's is just one of so many stories from that time, and the role the hall played during the war was very special. The staff that remained were incredibly proud of their colleagues going off to fight and kept their jobs open for them."

One who did not survive the war was cleaner Albert Rumbelow. A father of four who lived a stone's throw from the hall, he joined the army in 1914. Two years later, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) for Conspicuous Gallantry. His citation reads that he "exposed himself to machine gun and shell fire when going across the open to rescue a wounded man. Later he went under fire to fetch a stretcher".

He returned to England badly injured and died two months before Armistice Day in a military hospital in Ashford, Kent. He was buried in the local graveyard alongside other military personnel, becoming one of the few soldiers to be buried on English soil (because the government had taken the difficult decision not to repatriate the bodies of those killed in battle). A copy of Albert's DCM, along with his death certificate, will also be on display.

Those attending tomorrow's event will be able to handle an extraordinary range of programmes, almost 100 years old, that remain in good condition. These include one for the 1915 Great Bazaar, at which people bought goods for parcels to be sent to the Front. John Nash and John Singer Sargent were among the artists who donated original items, with the latter sketching caricatures in one of the hall's loggia boxes.

Other programmes, such as one entitled Christmas in Wartime, from 1915, and a "special concert to 10,000 wounded soldiers", highlight the patriotic flavour of the events.

Ms Harper said: "This tale of pride, patriotism and personal sacrifice will be illuminated by details that bring home the extraordinary atmosphere in the country at the time, like the blacking out of the building from 1914 – with black cloth covering its roof, and blinds over each of the 98 windows."

In 1914, a personal side entrance for the monarch was completed but the stress of war on the nation's finances meant that it was another five years before the hall's Royal Retiring Room was finally furnished.

Although the public was warned at concerts what to do in the event of an air raid, the music continued – two concerts a week usually. The musical content changed, however, as the grim reality of conflict struck home. "England's Call" and "The Rally Call" were typical of the jingoistic nature of music during the early war years but, with the mood darkening as the death toll mounted, songs became more sombre and cynical. "Oh! It's a Lovely War", with its sarcastic and anti-establishment lyrics, reflected the change.

In October 1917, the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and Chancellor, Andrew Bonar Law, arrived on stage to persuade the nation to invest in war bonds. Just over a year later, the war was over. The Royal Albert Hall marked its end with a thanksgiving service attended by royalty and the Victory Ball, held on 27 November 1918, the first ball in the building since 1913.

Ms Harper said: "In many ways, the story of the Royal Albert Hall during the Great War is also the story of Britain: from the grand rallies and parades held at the venue to the often-harrowing experiences of staff who enlisted as soldiers."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments