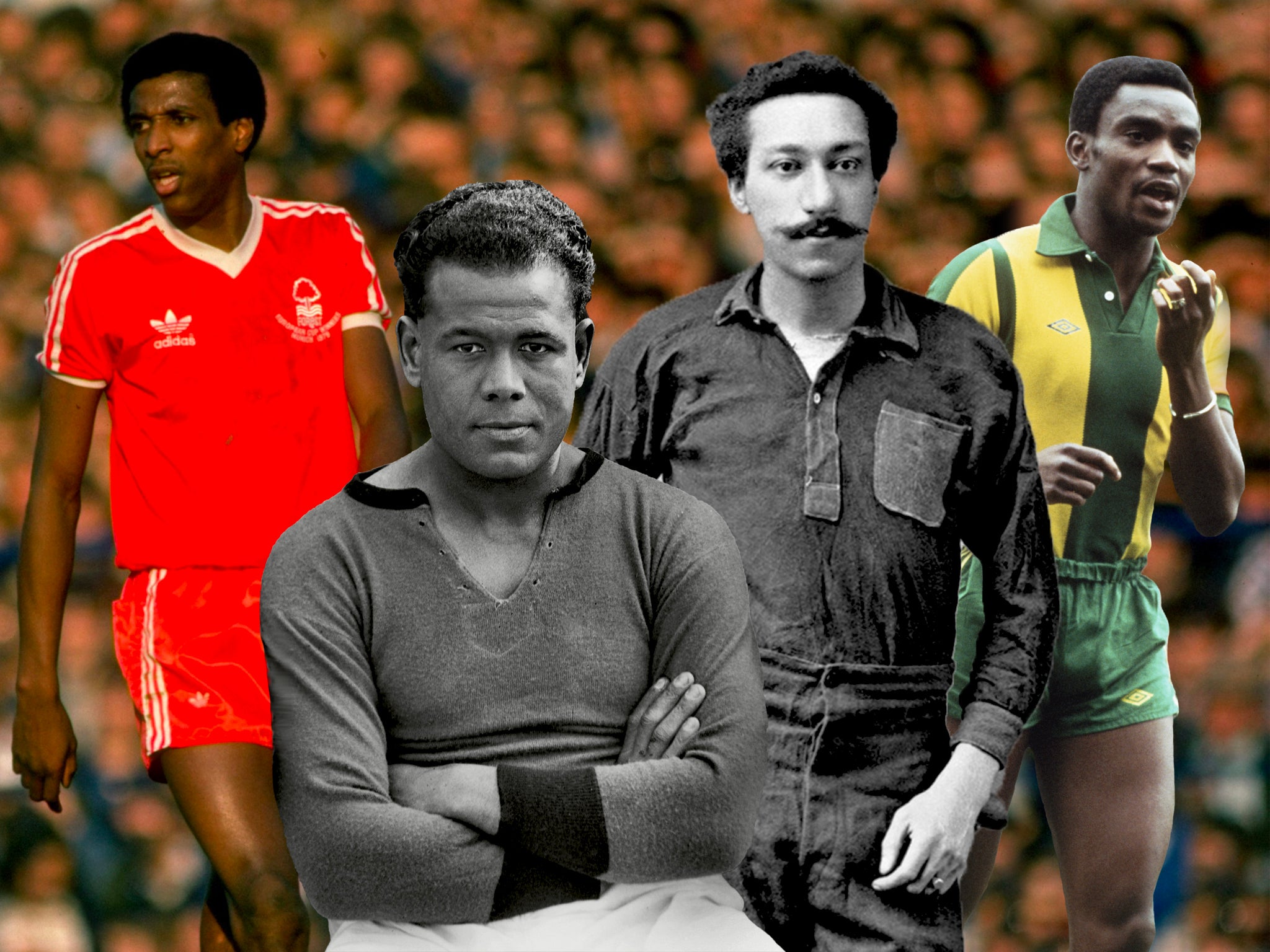

Pioneers, prejudice and the Pele of Barnsley: first black footballers at all 92 league clubs remembered

Remarkable new book started as sporting project, say authors, but turned into wider social history charting black British experience

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On the morning of 6 October, 1925, Jack Leslie – a prolific striker with Plymouth Argyle FC – was called into his manager’s office and given the news that should have changed his life: he had been selected for the upcoming England squad.

He was 24 at the time and in formidable form. “An inside-forward of great ability [who] will soon work his way into representative matches,” the Northern Whig newspaper declared of his call up.

Yet it never happened.

Days after the International Selection Committee picked Leslie on the strength of his goal-scoring record, they were, so it is said, shown a picture of him.

To their apparent surprise, a black man looked back at them. They had not known he was the son of a Jamaican sailor and English seamstress. Once made aware, they dropped him from the squad.

“They found out I was a darkie,” Leslie, who was born and bred in London, later recalled. “I suppose that was like finding out I was a foreigner.”

This moment of heartbreak is just one recorded in an oft-devastating – yet oft-uplifting – new book charting the first black players to appear for all 92 league clubs.

Bill Hern and David Gleave, authors of Football’s Black Pioneers, say they set out four years ago to write a dip-in-dip-out tome that would appeal to sports fans.

Yet the result is only ostensibly about the (not always) beautiful game.

Rather, what emerges over 92 wildly different mini-biographies, is a far wider social history about the black British experience over the last 130 years, touching on everything from slavery to Windrush and black lives mattering.

Here, writ large in often agonising detail, is racism, prejudice, isolation and the loneliness of going where others have not yet been. In one heart-rendering chapter, Paul Canoville, who played for Chelsea’ in the Eighties, is barracked game after game – by his own fans. “It was crushing,” he recalls. In another, Howard Gayle, who played for Blackburn Rovers in the same era, becomes so enraged by abuse, he jumps into the packed Nuttall Street paddock to confront supporters.

“We started writing a book about football,” says Gleave today. “But as we progressed, we found we were uncovering more and more stories that made us realise, actually, these lives offered a real sense of a wider black British history; they touch on so many issues that members of the black community – whatever their job or position – have faced down the years.”

Yet this is by no means a bleak read.

The lives here are shot through with triumph, defiance against stacked odds and genuine, real-life heroism.

One star – Walter Tull who played for Spurs and Northampton – would die a second lieutenant on the battle fields of World War One; several others are considered such trailblazers they have since been made MBEs (or, in Howard Gayle’s case, refused the offer of an MBE). One, Lindy Delapenha, is almost certainly the only Burton Albion player ever to be commemorated on a Jamaican postage stamp.

“These are stories of people who overcame huge obstacles,” says Gleave. “To get in this book, they not only had to be great footballers but probably better than their white peers – so these are people who have triumphed against the odds and I think that does make their stories uplifting.

“None of these guys had it easy. You would be hard pressed to find a single one, no matter how talented, who found their playing days or lives a doddle. It was difficult and their success was a testament to their characters.”

There are moments of levity here too. In a chapter on Willie Clarke – who, on Christmas Day 1901, became the first black player to score a league goal while playing for Aston Villa – it is noted that his marriage to a white girl was disproved of by her father. Ada Higginbottom’s dad was not, it is hinted, overly-concerned about Clarke’s Guyanese heritage but was none too keen on his daughter wedding a footballer.

In other notable sections, Arthur Wharton is toasted as the league’s first black footballer (he played for Preston North End in the 1886 season) and Viv Anderson as the first black England international (53 years after Leslie was dropped). “The changing room was chaotic,” the midfielder says of his 1978 debut against Czechoslovakia. “Telegrams [were] arriving from well-wishers including the Queen and Elton John.”

Elsewhere, the oft-overlooked Dennis Walker is celebrated. Who was he? The only black Busby Babe. Also here, for different reasons, is Steve Mokone, the self-proclaimed Pele of South Africa who arrived at Barnsley in 1961, played one game, and caused so much (unspecified) disruption the club terminated his contract within five days. He later served 12 years in a US prison for assault. A character, as they say.

Gleave and Hern themselves started work on the project four years ago almost to the month.

Gleave is 68, white and a retired civil servant by trade. But in 1981 – the year of the Brixton riots – he married Roxanne, a Guyanese teacher, with who he has three mixed-race children, all now grown-up.

“As a couple, we knew from first-hand experience there was very little black history taught in school so we decided very early that we would have to teach this part of their heritage,” he says today. “We were always keen to stress that having this mixed heritage gives you not just one culture to draw on, but two. It is far more interesting and exciting.”

Thus, began a three-decade journey into black history which has seen him produce books and online packs about everything from slave campaigner Olaudah Equiano to composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

Then, four years ago, as he and Hern concluded an educational project on black soldiers who fought in World War One, the latter suggested the idea that would become this new book.

Hern is 64, also white and a retired civil servant.

His passion for history had led him to focusing on black issues, he says, “because it is an area that is so rich but so often overlooked".

Yet when he suggested this new project, Gleave was initially skeptical.

“My first reaction was that it was a really good idea," the Crystal Palace fan from London says. “But my second thought was that it was also a huge amount of work. I was right on both those counts.”

That work included speaking to clubs (“mainly useless”), sifting through old newspapers and programmes, chatting with local historians and going through more birth, death and marriage certificates than either men can count.

Online fan forums proved hugely useful – although not always. “On several occasions we had people saying to us something like, ‘Oh yes, we had an Egyptian prince play for us in the Twenties and he always played in bare foot’,” says Gleave. “There are various stories of that sort doing the rounds, although sorry to say we never found any Egyptian princes.”

They interviewed about 20 of the pioneers, with Hern – a Sunderland fan now living in Yorkshire – speaking to Viv Anderson and Chris Kamara. The latter – today a semi-legendary pundit – had no idea he had been a trailblazer with Swindon, despite it being splashed all over the local newspaper at the time.

“I also interviewed Yeovil Town’s,” says Gleave, ruefully. “Then they dropped out of the football league so we couldn’t include it.”

If the book has a central message, he says, it may be that work still needs to be done on tackling prejudice – in football and beyond.

It points out that there remains, even in 2020, few black managers in the game.

“I think it’s quite easy for white liberal people to say things are getting better but actually, I think if you’re involved with the black community, it’s fairly obvious that things aren’t altogether better,” he says. “My wife and I were abused on the street only a year ago for no reason so these things are still happening.

“Are they getting better? I don’t know, maybe. But what I am sure of is it’s easy to exaggerate how much better they are, and that is not a trap we should fall into. There is still huge amounts of work to be done,.”

* Football’s Black Pioneers is published by Conker Editions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments