Number of EU citizens moving to UK for work has halved since Brexit vote

'The weak pound and the uncertainty over Brexit are likely to be prime explanations' for decline, think-tank says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The number of EU citizens moving to the UK for work has halved since the Brexit referendum.

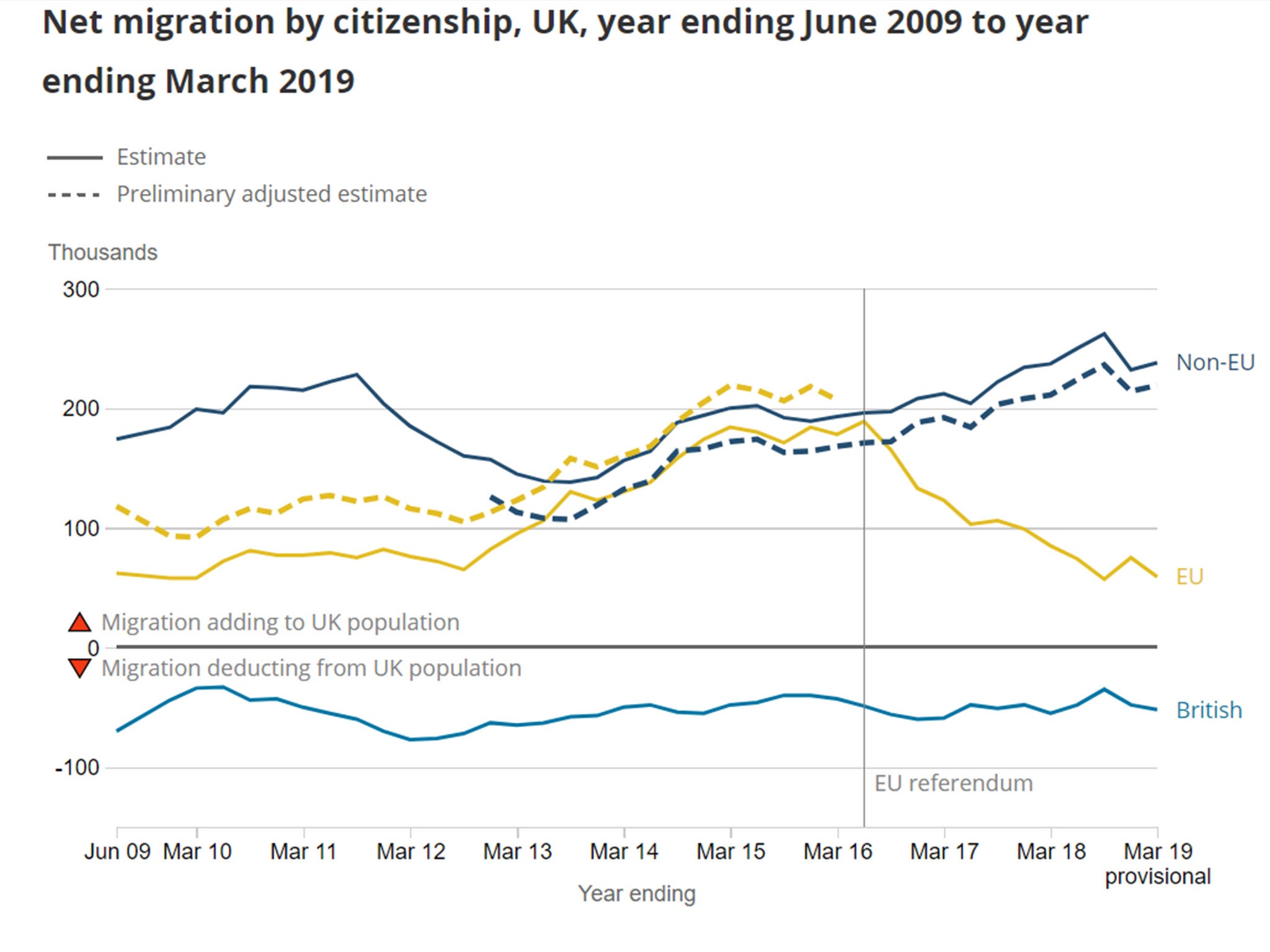

Statistics show the number plummeted from 190,000 in the year to June 2016 to 92,000 in the year to March.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said the figures were based on “adjusted estimates” following its admission that EU migration had been underestimated.

Immigration for work from outside the EU has remained “broadly stable” since late 2017 but arrivals now include more job holders than jobseekers.

Overall, net migration stood at 226,000 in the year, with 612,000 people moving to the UK and 385,000 leaving.

Jay Lindop, director of the ONS Centre for International Migration, said: “Our best assessment using all data sources is that long-term international migration continues to add to the UK population.

“The level has been broadly stable since 2016, but there are different patterns for EU and non-EU citizens.

“Using the data sources available to us, we can see that EU immigration is falling. There are, however, still more EU citizens moving to the UK than leaving, mainly for work, although the picture is different for EU8 citizens, with more leaving the country than arriving.

“In contrast, non-EU immigration has stabilised over the last year, after gradual increases since 2013.”

Labour said the figures showed that the government's target of reducing net migration to 100,000 a year was "unworkable".

Diane Abbott, the shadow home secretary, said: "Now the Tories want to make this even worse by excluding all underpaid workers, and insist on calling them unskilled. This would do enormous damage to our public services, including the NHS, as well as to UK industry."

A report released by parliament's Migration Advisory Committee in May said a large increase in skilled migration from outside the EU was needed to plug gaps in key jobs.

Overall, EU net migration has fallen to 59,000 – less than a third of a peak of 219,000 in the year to March 2015 – while non-EU net migration is 219,000.

The number of arrivals from EU8 countries – the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia – has seen the steepest drop since Brexit.

In the year to March, 7,000 more EU citizens left than arrived, with 43,000 departing.

The Institute for Public Policy Research said the decline was “due to a number of factors, but the weak pound and the uncertainty over Brexit are likely to be prime explanations”.

Marley Morris, the think tank’s associate director for immigration, trade and EU affairs, said: “If the government wants to step up its no-deal preparations, it should concentrate on reassuring EU citizens living in the UK of their right to remain after Brexit.

“Unhelpful briefings about an abrupt end to freedom of movement on day one of a no-deal will do little to dispel anxiety among EU citizens.”

Free movement for EU citizens would end immediately in the event of a no-deal Brexit on 31 October, according to new Home Office plans.

Previously, ministers had intended to delay scrapping free movement until new rules were in place, with a bill stuck in the Commons and fierce rows over what those rules should be.

The number of people granted asylum rose by 61 per cent to 10,555 in the year, while grants of humanitarian protection rose by a third to 1,126. Some 5,691 people arrived under resettlement schemes and 1,147 were granted an alternative form of leave.

Overall, the number of people granted protection in the year was the highest since the year ending September 2003, the ONS said.

On Wednesday, it admitted that it had underestimated levels of EU migration and overstated non-EU migration.

As a result the ONS downgraded the status of its quarterly immigration figures it compiles to “experimental”.

“Our research has clearly shown that no single source of data can fully reflect the complexity of migration,” a statement said.

“However, when we look at all available sources together it provides a much clearer picture.”

The immigration minister, Seema Kennedy, said: “These statistics show that highly skilled workers, such as scientists, doctors and nurses, continue to be attracted to the UK, boosting our economy and demonstrating that this country is a great place to study, work and do business.

“Leaving the EU means we will have full control over who can come to the UK, which means ending free movement as it currently stands and establishing a points-based immigration system which attracts the brightest and the best from around the world.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments