Scientists discover clue which could explain why early pregnancies fail

‘By combining our new technology with advanced sequencing methods, we have delved deeper into the key changes that take place at this incredible stage of human development, when so many pregnancies unfortunately fail’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new study into the early stages of embryo development could lead to a deeper understanding of why many pregnancies fail, researchers say.

Scientists at the University of Cambridge identified key molecular events that occur within the second week of gestation, in one of the most critical phases of embryonic development.

Between seven and 14 days after an egg is fertilised, scientists discovered that a group of cells outside the embryo called the hypoblast triggers the development of the embryo’s head-to-tail body axis — the initial step in the formation of the human body.

The study, published in Nature says: “Failure of development during this time represents one of the major causes of early pregnancy loss in patients undergoing assisted contraception treatments”.

Very little is currently known about human embryo development once it has implanted into the uterus because of ethical restrictions on the use of human embryos in research.

Significant embryonic research has been carried out on mice and cynomolgus monkeys, but there are subtle differences in the ways that human cells arise from hypoblasts compared with mice and monkeys.

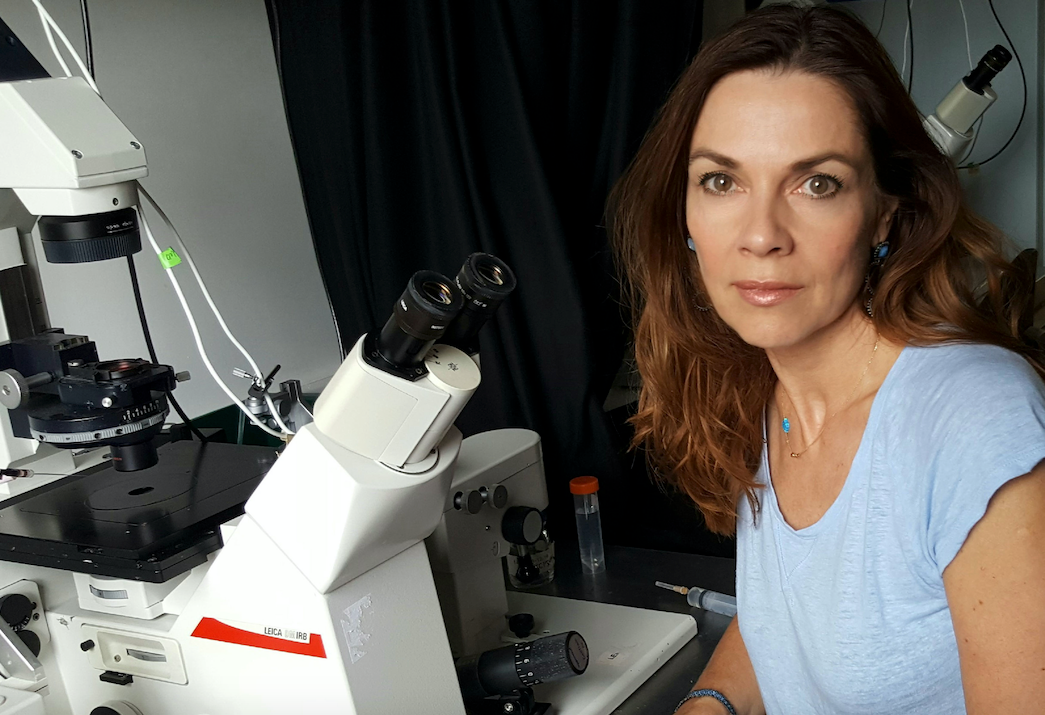

But in 2016, Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, of the department of physiology, development and neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, pioneered a technique to develop human embryos outside the body, which allowed them to be studied until the 14th day of development.

This technique is aligned with the UK’s ethical guidelines around embryonic research.

Working in collaboration with the Wellcome Sanger Institute on the new study, Professor Zernicka-Goetz’s team used this methodology to better understand what happens at a molecular level during this early embryonic stage of human development.

Their findings present the first evidence that the hypoblast send a message to the embryo that initiates the development of its head-to-tail axis, also determining which part of the embryo becomes the “head”, and which part the “tail”.

Professor Zernicka-Goetz said: “We have revealed the patterns of gene expression in the developing embryo just after it implants in the womb, which reflect the multiple conversations going on between different cell types as the embryo develops through these early stages.

“We were looking for the gene conversation that will allow the head to start developing in the embryo, and found that it was initiated by the cells in the hypoblast — a disc of cells outside the embryo.

“They send the message to the adjoining embryo cells, which respond by saying, ‘OK, now we’ll set ourselves aside to develop in the head end’.”

She added: “Our goal has always been to enable insights to very early human embryo development in a dish, to understand how our lives start.

“By combining our new technology with advanced sequencing methods, we have delved deeper into the key changes that take place at this incredible stage of human development, when so many pregnancies unfortunately fail.”

The study results also confirmed that the formation of the body axis in human embryos shows similarities to the formation of the body axis in mice and monkeys, despite significant differences in the positioning and organisation of the cells.

All work in the study was funded by Wellcome and carried out with the oversight of the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments