Daffy duck, coconuts and raccoons: When do memes, emojis and gifs become hate crimes?

‘I’m going to be brought down by a Daffy Duck GIF? I felt anger,’ one person told The Independent. Nadine White looks at how people can fall foul of social media memes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From a man being taken to court for posting a raccoon picture on social media to a British-Asian woman being charged after holding a placard depicting ministers as coconuts, concerns are mounting about how criticising politicians can land Black and Asian people with criminal records.

Increasingly, emojis and memes are being used as a form of political criticism, in these cases to call out members of an ethnic minority who are perceived as pandering to white supremacy. But a number of people have been investigated by the police as a result of using terms such as “coconut”, “c**n” and “tap-dancer” to criticise public figures who share the same ethnicity.

Critics believe they are making legitimate points, while those on the receiving end have said the images amount to racial abuse.

Those making complaints about the images are using anti-racist legislation. But campaigners are concerned the law is being weaponised against people from minoritised communities who have expressed critical views on social media, particularly against right-wing politicians.

The accused could face sentences of up to two years in prison if convicted.

Michael Buraimoh, chief executive of campaigning group Race on the Agenda, told The Independent: “It is deeply troubling to see anti-racist legislation meant to protect members of our community increasingly being weaponised against us.

“‘Racism’, whilst notoriously difficult to define, generally involves individuals with more power oppressing or victimising those with less power. The decision to open a police probe into a social media dispute between two members of our racialised and generally marginalised community is wholly disproportionate.”

A number of images depicting coconuts, raccoons and tap-dancing have been posted online by Black and Asian users.

“Coconut” and “raccoon” or “c**n” are used to imply that a member of a minority community is acting as an apologist for racism, with coconut suggesting the person is brown on the outside but white on the inside.

Being described in such terms is no compliment. However, is it worthy of criminalisation? This is where the debate rages on.

For example, a raccoon emoji on X, formerly Twitter, landed a Black man in court earlier this year in a case revealed by The Independent. In March, he was acquitted of hate crime charges.

The man, aged 26 at the time, was reported to the police for posting the image during a heated exchange with a politician who is also of ethnic minority heritage, in September 2022.

Following the police complaint and further enquiries, the man was charged with racially aggravated malicious communications and appeared in Wood Green Crown Court in London in February. However, a jury returned a “not guilty” verdict on both counts after a three-day hearing.

Another Black man was recently investigated after his tweet of a Daffy Duck tap-dancing emoji led to a police complaint during an online row about race.

The HR professional, who has asked not to be named for fear that he may lose his job, became the subject of Metropolitan Police enquiries that lasted seven months, and was interviewed under caution and questioned at work.

“I’m going to be brought down by a Daffy Duck GIF? I felt anger,” he told The Independent, defending his use of the GIF as “critique of political ideology”.

This particular GIF image and the idea of a “tap dancer” is often used within Black communities to describe a Black person who aims to appease racists by denying the existence of racism, while appearing to be amenable, entertaining or both.

As well as raccoon emojis and tap-dancing GIFs, coconut imagery is also used online in the context of political criticism of Black and Asian politicians, as well as in conversations.

This week, Marieha Hussain, a British-Asian woman, was charged with racially aggravated public disorder after being pictured holding a banner depicting Rishi Sunak and former home secretary Suella Braverman as coconuts, while attending a pro-Palestine march in November. She is due to appear at Wimbledon magistrates’ court on 26 June.

Ms Hussain’s case has fuelled a debate about the extent to which terms such as “coconut” and “c**n” are racist when used by people in minority communities.

Ms Braverman came under fire for “stoking racial tensions” with offensive rhetoric about Black and Asian communities when she called pro-Palestine protests “hate marches”, while Mr Sunak has been criticised for presiding over divisive policies such as his Rwanda deportation scheme.

In light of these cases, campaigners have raised concerns that anti-racist legislation is now being weaponised against ethnic minority groups.

Dr Asim Qureshi, research director at advocacy group CAGE International, which has advocated for Ms Hussain, said: “We have reached late-stage diversity, equity and inclusion, where legislation enacted to ostensibly protect minorities from racial discrimination, is now being weaponised against people of colour for expressing their political views.

“It is why CAGE International focuses on the systemic, rather than seeking to ameliorate a broken system of injustice. Racism never went away, it was just subverted by racists into being something that could become everything except doing the actual work of anti-racism”.

People falling foul of the law are largely being questioned and prosecuted under the Malicious Communications Act of 1988 which makes it illegal in England and Wales to “send or deliver letters or other articles for the purpose of causing distress or anxiety”.

Black and Asian people are already arrested and prosecuted at higher rates than their white counterparts and comprise 27 per cent of the prison population despite making up only 18 per cent of the population of England and Wales, according to government data.

There are concerns that police clamping down on such language means that people from minoritised communities, already more at risk, face a heightened risk of imprisonment.

The National Black Police Association (NBPA) recently told Channel 4 that laws designed to crack down on racial hate speech are being weaponised against ethnic minorities.

“I think the increase is probably due to the external environment and the polarised communities that we see ourselves in at the minute,” said NBPA president Andy George.

“I think policing needs to make sure that we don’t get caught up in anything like a culture war, [and] we make sure that we stay impartial.”

Many commentators say that terms such as “coconut”, “c**n” and “tap dancer” are not racist when used intra-communally within Black and Asian communities.

Lawyer Dr Shola Mos-Shogbamimu told The Independent the terms do not amount to a hate crime or racism. She said: “Misappropriation of ‘coconut’ by institutionally racist structures like the police is intentional and solely to push an agenda of white supremacy.”

Moreover, critics of police complaints have pointed to the example of Tory donor Frank Hester’s comments calling for Labour MP Diane Abbott to be shot, adding that she makes him want to hate all Black women. They have argued that senior Conservative Party politicians’ apparent failure to report him to the police for hate speech while suggesting that he should be forgiven, contrasts with the treatment of the men at the centre of emoji-gate and the Daffy Duck debacle.

Conversely, concerns have been raised that terms like “coconut” are indeed racist and warrant police intervention.

Sunder Katawala, founder of the British Future think tank, said it is “no way to make a political argument” and “unlawful racist abuse”.

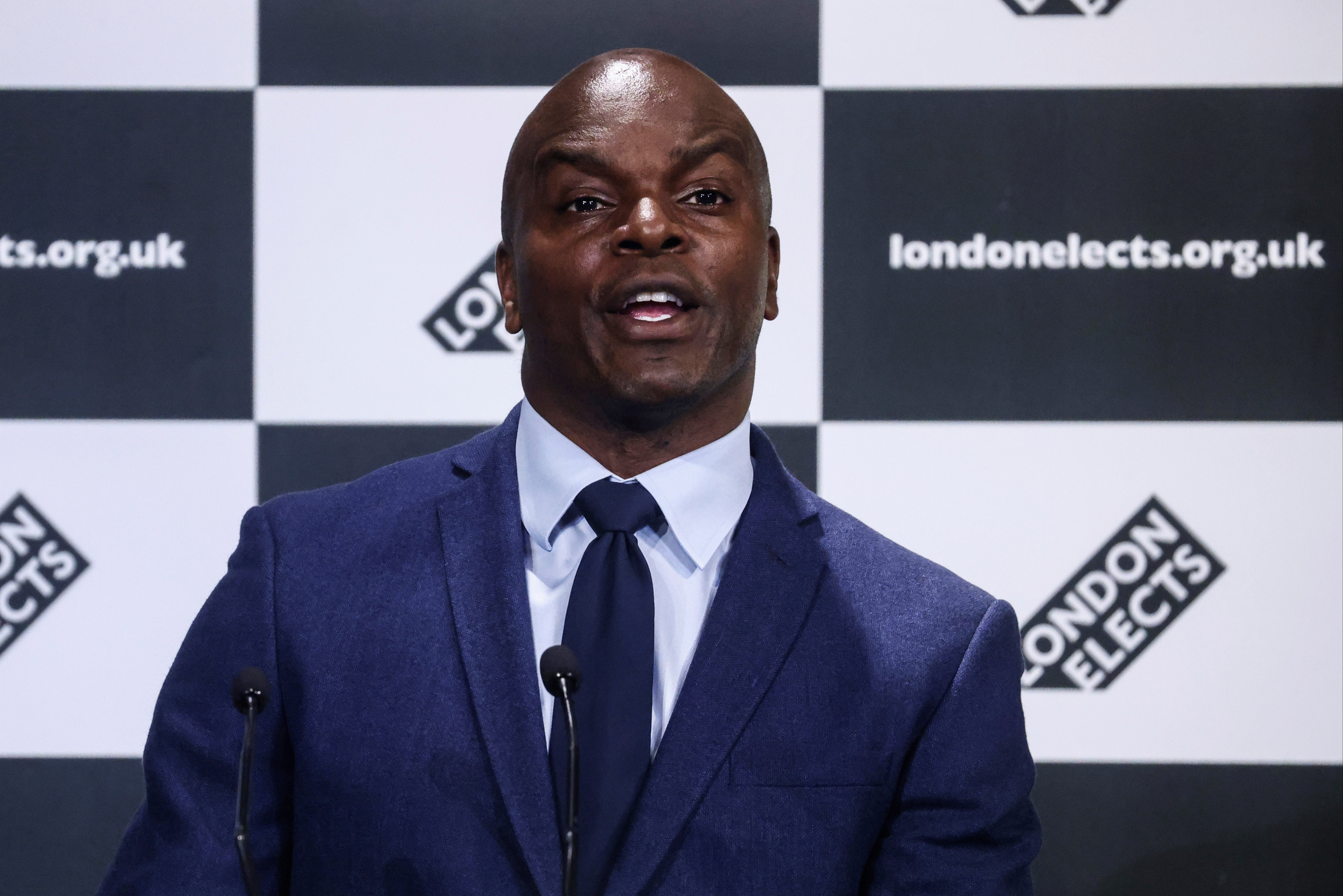

Lord Shaun Bailey, a Conservative peer, expressed sympathy with Black politicians who report other Black and Asian people to the police for calling them names such as “coconut” – though said he would not do that.

“What’s interesting being a Black politician is you get it from both ends: you’re either not Black enough or you’re too Black. And that leads to comments such as ‘coconut’, ‘Bounty’. On a personal level, if you’ve been attacked so much, you have to say ‘enough is enough’,” Lord Bailey recently told Channel 4.

“Is it hypocritical that I haven’t reported people from the Black community [to the police]? I would say no because that’s a personal decision and I understand the pressures that might cause on my community.”

It is unlikely the debate will be settled any time soon. After all, complaints to the police about language used by people within marginalised groups go back more than a decade.

In 2010 Liberal Democrat councillor Shirley Brown was found guilty of racial harassment after she called her political opponent, South Asian Conservative Jay Jethwa, a “coconut” during a debate at Bristol City Council the year before.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments