UK’s poorest households felt brunt of rising food prices in cost of living crisis

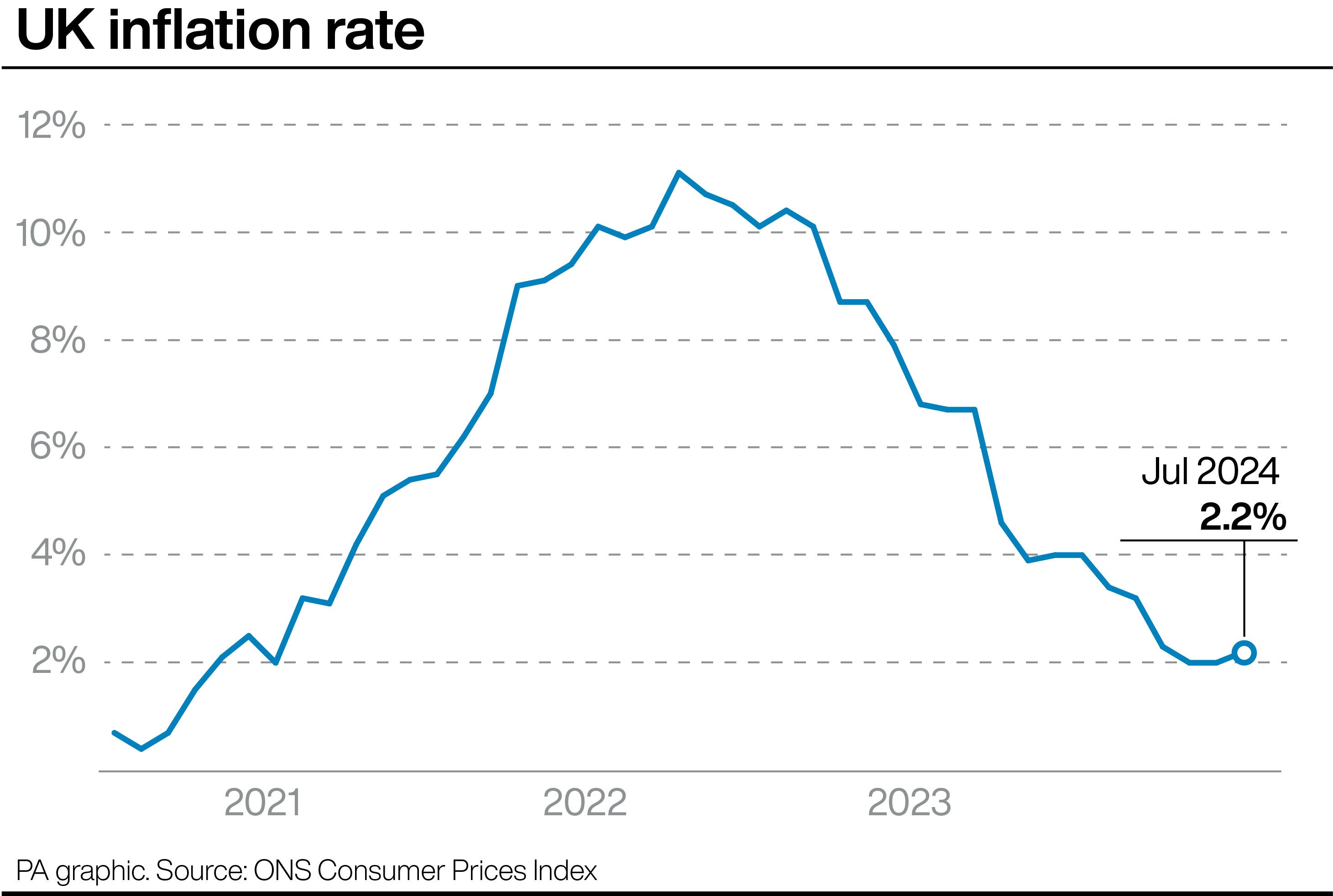

It comes as fresh inflation data from the Office for National Statistics found that inflation ticked up to 2.2 per cent in July

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain’s poorest households saw their shopping bill rise far more than the rich in the last few years, as the cost of the cheapest groceries jumped sharply compared to premium brands.

New research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) found “cheapflation” between 2021 and 2023 hit households with tighter budgets, during the height of the cost-of-living crisis.

Poorer households paid 29.1 per cent more for their food over the period, while much wealthier households witnessed a 23.5 per cent increase, the research found.

Food and drink inflation surged from 2021 in the face of post-pandemic supply and labour pressures and was accelerated further in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine caused energy prices to spike.

This comes as UK inflation rose to 2.2 per cent in July, marking the first increase this year.

The latest figures mean that prices are rising faster across the country than in previous months, but still at a slower rate than in 2022 and 2023 when households and businesses were being squeezed during the peak of the cost crisis.

Food and drink inflation surged from 2021 in the face of post-pandemic supply and labour pressures and was accelerated further in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine caused energy prices to spike.

As a result, food and drink prices rose by 28.4 per cent between September 2021 and September 2023, compared with overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation of 15.7 per cent.

Nevertheless, the IFS said this inflation was disproportionately focused towards typically cheaper products.

Value brands of staple grocery products, such milk, pasta and butter rose in price by 36 per cent over the two-year period, while more expensive versions of the same items rose by just 16 per cent.

During the cost-of-living crisis, British households also shifted towards cheaper varieties of goods over this period to deal with the pressure on their budgets.

The share of household spending on the cheapest 10 per cent of products grew by 2.2 per cent between 2021 and 2023.

In what it said was an “unprecedented” disparity in inflation rates across income classes, the IFS calculated that if the poorest 25 per cent of households had faced the same inflation rate for groceries as the richest 25 per cent, their annual food bills would have been cut by £100.

Tao Chen, a research scholar at the IFS, said: “Widespread cheapflation pushed up the prices of the most inexpensive varieties of grocery products over the last two years. This hit poorer households harder.

“Individual households will almost always experience a different rate of inflation to headline numbers such as the CPI because these measures are based on average consumer spending patterns across the economy.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments