Charles Darwin notebooks stolen from Cambridge library reported missing after 20 years

Missing manuscripts now on national Art Loss Register as well as Interpol database

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two of Charles Darwin’s notebooks have been declared stolen, almost 20 years after they were first reported missing from Cambridge University Library.

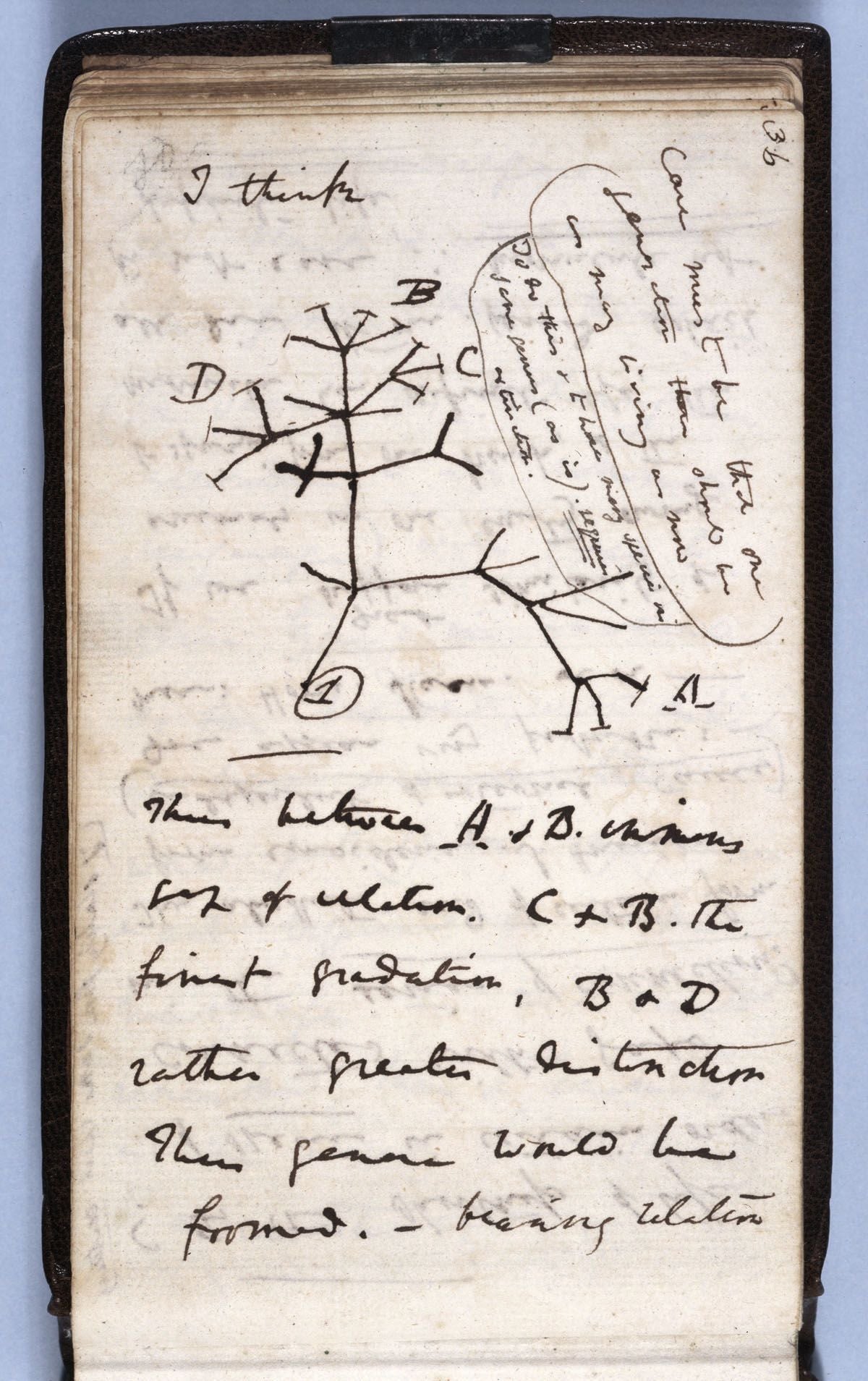

Cambridgeshire Police are now investigating the suspected theft of the small red-leather-bound manuscripts, one of which contains the naturalist’s famous Tree of Life drawing on the relationship between species.

The matter was referred to the police in October, after they were not located during an extensive search of the library’s special collections, including the entire Darwin Archive, earlier this year.

The notebooks, which are worth millions of pounds, were last seen in November 2000, when they were taken to a temporary studio in the library’s grounds to be photographed.

Two months later, a routine check found they were missing. However, librarians at the time assumed they had just been misplaced in the library, whose shelves run to a total of 210 km, roughly the distance between Cambridge and Southampton.

Dr Jessica Gardner, who has been the director of library services since 2017, now believes otherwise, telling BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “I have reluctantly come to the conclusion that these notebooks have probably been stolen.”

The university’s librarian, who said she was “heartbroken” by the loss, added that security policy was much more thorough now than 20 years ago, with new strong rooms and CCTV in place.

“Security policy was different 20 years ago. Today any such significant missing object would be reported as a potential theft immediately and a widespread search begun. We keep all our precious collections under the tightest security, in dedicated, climate-controlled strong rooms, meeting national standards,” she said.

The missing notebooks are now on the national Art Loss Register as well as on Psyche, the name given to Interpol’s database of stolen works.

Cambridgeshire Police are also appealing to anyone with information about these “priceless artefacts” to come forward.

Detective Sergeant Sharon Burrell, of Cambridgeshire Police, said: “I hope the publicity surrounding their potential theft jogs someone’s memory and leads to information coming to light that results in their return. Due to the time since their disappearance, information from the public will be very important to this investigation.”

Dr Mark Purcell, deputy director of Research Collections at Cambridge, said it is unlikely they could have been sold on the market, adding that they could have “gone to ground” instead.

He expressed hope that the notebooks would be returned just like stolen items from London’s Lambeth Palace, which were taken during the Second World War and came to light 40 years later as “the consequence of a deathbed crisis of conscience”.

The university chose to go public with the news about Darwin’s notebooks on 24 November - otherwise known as Evolution Day - because it was on this date in 1859 that the scientist’s landmark On the Origin of Species was first published.

This work included a more fully developed tree of life from the one he jotted down 22 years earlier in one of the missing notebooks.

Referring to the earlier sketch, Jim Secord, emeritus professor of history and philosophy of science at Cambridge University, said: "It's almost like being inside Darwin's head when you're looking at these notebooks.”

"You have the sense of him working through these ideas at great speed and that kind of intellectual energy which I think the notebooks really convey,” he added.

Prof Secord said it was “a tragedy” that the real copies had gone missing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments