‘A terrible injustice’: Chagos islanders fight for passports 50 years after being forcibly evicted by Britain

The British government expelled those living in the Chagos Islands in order to lease the largest atoll to the US as a military base. Five decades on, the Chagossian diaspora stretches from Crawley to Mauritius. Unable to return home, the former islanders want to exercise their right to UK citizenship, writes Rory Sullivan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Half a century after the UK forcibly evicted them from their island homes, Chagossians are still fighting for British citizenship.

The inhabitants of the Chagos Islands – an archipelago of around 60 islands in the Indian Ocean, located almost 6,000 miles from England – were kicked out of their homeland between the late 1960s and 1973 to make way for a US military base on Diego Garcia, the largest of its atolls. Initially sent to Mauritius and the Seychelles, the former inhabitants and their descendants are not permitted to go back permanently.

For this reason, the Chagossian diaspora now stretches from Port Louis to Crawley. In their exile, those born on the islands, as well as their descendants, lobby for their right of return and, in the shorter term, for a secure life in the UK.

But under Home Office rules introduced in 2002, not all the expellees’ children and grandchildren qualify for British overseas territory citizenship, which would be a step towards securing a British passport. As a result, families continue to suffer the pain of separation.

This has had a profound effect on people like Frankie Bontemps, 52, whose parents were both born in the Chagos Islands, which are known to the UK as the British Indian Ocean Territory.

The NHS worker, a Crawley resident like several thousand other Chagossians, has two older sisters who are unable to move to England from Mauritius. Eight of his aunt’s nine children are likewise barred from the UK. There are hundreds of other people in a similar position to them, he said.

Bontemps, who helped found the community group Chagossian Voices, explained the arbitrary nature of the British immigration system towards Chagossians by pointing out his own luck. “I was born on 13 May 1969, but if I was born roughly 20 days before I would not have been granted British citizenship,” he said.

The 52-year-old, who arrived in England in May 2006, called on the government to change its policy. “It’s dividing families. This division has been going on for 53 years, starting with the forced exile to Mauritius.”

Earlier this month, I met Bontemps and other Chagos islanders who had gathered for lunch in Crawley, the Sussex town that is home to the UK’s largest Chagossian population. Speaking of their difficulties, many broke down in tears during our conversations.

As the afternoon of 8 December progressed in a strongly lit community centre, discussion invariably returned to a vote in parliament the previous day. The local Tory MP, Henry Smith, had sought to get all Chagossians British citizenship under an amendment to the controversial Nationality and Borders Bill.

However, it was defeated by 309 votes to 245 in the Commons. In the preceding debate, Smith had said it was time to correct “over half a century of consistent injustices”.

Smith told me in November that he had first read about the Chagos Islands expulsion at university. “I thought at the time that it was a colonial story you’d expect 200 years ago taking place just half a century ago,” he said. “It is really quite shocking that they were forcibly removed to make way for a military base.”

He described the defeat of his clause as “disappointing” but suggested that, with 245 votes, support for the issue was growing. The campaign would now focus on amendments in the House of Lords, the MP added.

A Home Office spokesperson claimed that the government had voted against the Smith amendment because it “would have created inequity between different groups of British nationals and their descendants”. Chagossians counter that their case is unique among former inhabitants of British overseas territories, as they alone are prevented from living on their land.

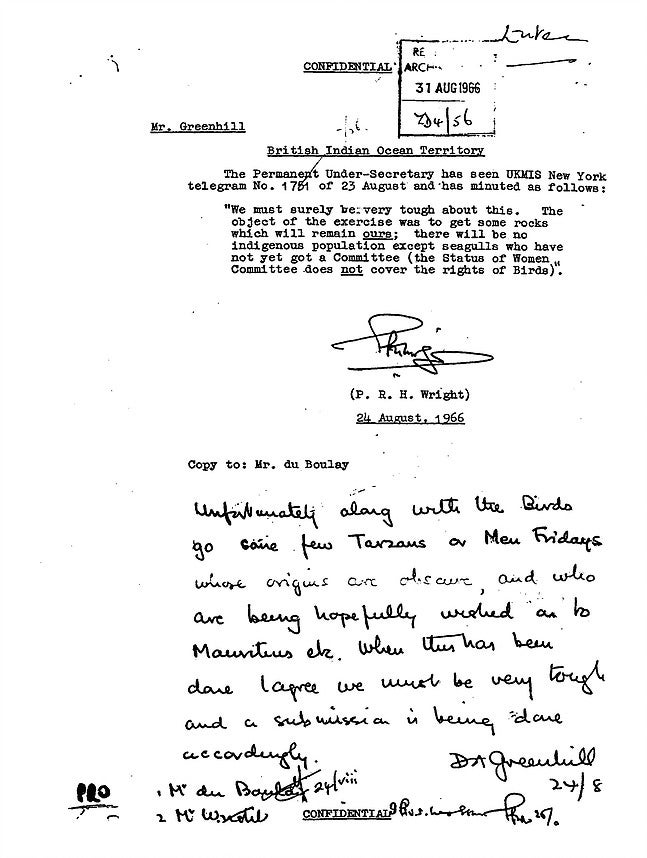

The department also said ministers would address “historic discrimination” against Chagossians in its New Plan for Immigration. An internal government memo, dated August 1966, shows such discrimination at its most flagrant, with Denis Greenhill, of the Colonial Office, describing the islanders as “Tarzans or Men Fridays” who would be “wished on to Mauritius”.

For the time being, Chagos islanders remain dissatisfied with the status quo. “If this amendment had gone through, it would have corrected a terrible injustice that our people have faced. We are really disappointed,” Bontemps told me.

This sentiment was echoed by Chagossians living in Mauritius. Jean-Claude Uranie, 64, some of whose family live in the UK, said the decision was upsetting. “We are heartbroken. Lots of people in England live separated from their children, separated from their husbands, separated from their wives.

“For more than 50 years we’ve been fighting for human rights. And we’re still fighting, fighting, fighting. It’s not easy, you know,” he said, his voice heavy with emotion.

Geraldine Baptiste, 23, is a third-generation Chagossian and the first member of her family to hold a university degree. Over the phone, she said the future was now unclear for many of her contemporaries.

“I know many young people like me who were awaiting the decision. I think now they will be very disappointed and some will not know what they will do in later life.”

Baptiste also noted that Chagossians are treated like second-class citizens in Mauritius. “We tend to face discrimination because we’re of African descendant. They tend to stigmatise our community, they think that we’re lazy. But that’s not true.”

Given such treatment, many community members in the UK do not want Britain to cede sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, which the government has said it will do when it no longer needs them for defence purposes.

Back in the community hall in Crawley, a Chagossian woman, who wished to remain anonymous, said the vote was “another tragedy” for her people. The current immigration rules mean that three of her nine siblings are unable to obtain British passports. The sadness caused by this separation was compounded recently when her brother in Mauritius fell ill, she said.

“What have we done to the British government to be treated in this inhumane way? This is our due: to have British passports,” she contended.

After Crawley – which is situated near Gatwick, the airport where the first Chagossians landed in the early 2000s – Manchester has the biggest group of Chagos islanders in the UK.

One of the community leaders there is Jimmy Elyse, 40, whose parents were ordered to leave their homes on Peros Banhos. At the age of 20, they boarded the last ship to leave the Chagos Islands in 1973.

Thirty years later, their son came to the UK not knowing English. He slept rough for a time, worked for 18 months in Crawley, and then moved to Manchester, where only a handful of other Chagossians lived. This number has now grown to several hundred, he estimates.

Like other Chagos islanders, Elyse is deeply troubled by the amendment result. Fighting back tears, he said: “I think it’s sad and horrible. We’re not here by choice. We can’t go back to our homeland.

“We were badly treated by the Mauritian government and now we’re badly treated by the British government as well.”

The 40-year-old told me via video call that Chagossians may need to resort to a hunger strike outside parliament to highlight their plight. He added that the UK government had shown itself capable of welcoming others, including an invitation to hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers fleeing China’s crackdown on freedom in their city. It should not be difficult to extend similar rights to all Chagossians, who number fewer than 15,000 people, he argued.

In addition to the issue of documentation, Elyse, who is currently taking GCSEs as part of his ambition to become a social worker, said his community was hamstrung by a lack of opportunities. Since many of his peers did not receive much of an education in Mauritius, they can only seek low-paid jobs in the UK, which means they do not earn enough money to meet the Home Office income threshold for bringing over their families.

To tackle the problem, he wants the government to set up an education and employment initiative for Chagossians, out of the £40m that ministers pledged to give the islanders in 2016. Five years on, very little of this money has so far materialised, a situation he compared to a father giving his son pocket money and then telling him he cannot spend it.

Elyse also mentioned how important it was for the government funds to be spent on establishing a Chagossian community centre, a space where their heritage could be preserved and where young and old alike could socialise. Those I spoke to in Crawley shared the same wish for their town.

However, more urgent concerns overshadow such ambitions. One is the difficulty of securing spousal visas, which has left families paying thousands in legal fees – often to no avail. Merlene Lamb, 75, who is married to a 78-year-old first-generation Chagossian, knows the feeling well.

Speaking in creole French through a translator, Lamb explained that her visa had been rejected four times in the last eight years, with the process costing her upwards of £6,000. She recently received a letter from the Home Office threatening deportation, and is worried that she will be separated from her spouse of 51 years, who was recently diagnosed with cancer.

“I am stressed, my blood pressure goes up every time. This whole thing makes me more ill. I don’t feel free,” she told The Independent, wiping her eyes dry with her scarf.

Speaking of Lamb’s trauma, and that of a man sat nearby who had spent £10,000 on five failed attempts to get his wife a visa, Bontemps said: “If this isn’t torture, I don’t know what is.” He fears that the situation could worsen because the government’s immigration laws are “getting tougher and tougher”.

Over lunch itself, I spoke to him and his friend Mylene Augustin, whose father was born in Diego Garcia and whose mother came from Peros Banhos. Both have travelled to the Chagos Islands on separate heritage trips from the UK.

“We have a beautiful island. We don’t need to go on holiday,” Augustin joked during her visit in 2010. “It’s like paradise,” she recalled 11 years later. “When I returned to England, I said, “If they let people back, I’ll be the first person to go.”

But for now, her struggle, and that of her people, continues. “We want to fight. It may be us who can live there or our children or our grandchildren,” Augustin said. “We will never give up. If the British government can’t do anything for us, they should let us go.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments