Calais crisis: Migrants that have made it to the UK reveal how Britain has matched their expectations

Three refugees who have made a home in the UK explain how hard it's to make a life away from their family and land

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How does the perception of the UK match up to the reality for migrants once they get here? We asked three people about their experiences.

Ramelle, 34, came to the UK alone in 2003 after fleeing the Democratic Republic of Congo where family members, including her mother, had been killed. She was denied asylum several times, and lived on the street in London before spending years sofa-surfing in Liverpool. With the support of the British Red Cross, she has completed her degree in biotechnology, and is working as a carer in Leicester while looking for work in the science sector. She was granted indefinite leave to remain in 2010.

“I had a better life back home, but I had to leave as I wanted to survive. If I had known how hard it would be, I would rather have died with my family. Before coming here, I had never known poverty or destitution. I had physical abuse there. Here I have had mental abuse [the asylum process]... that has led to me trying to kill myself many times. I have learnt to seek help when I need it, and the people from the charities who have helped me have become my friends and family. I am isolated and I feel scared most of the time.”

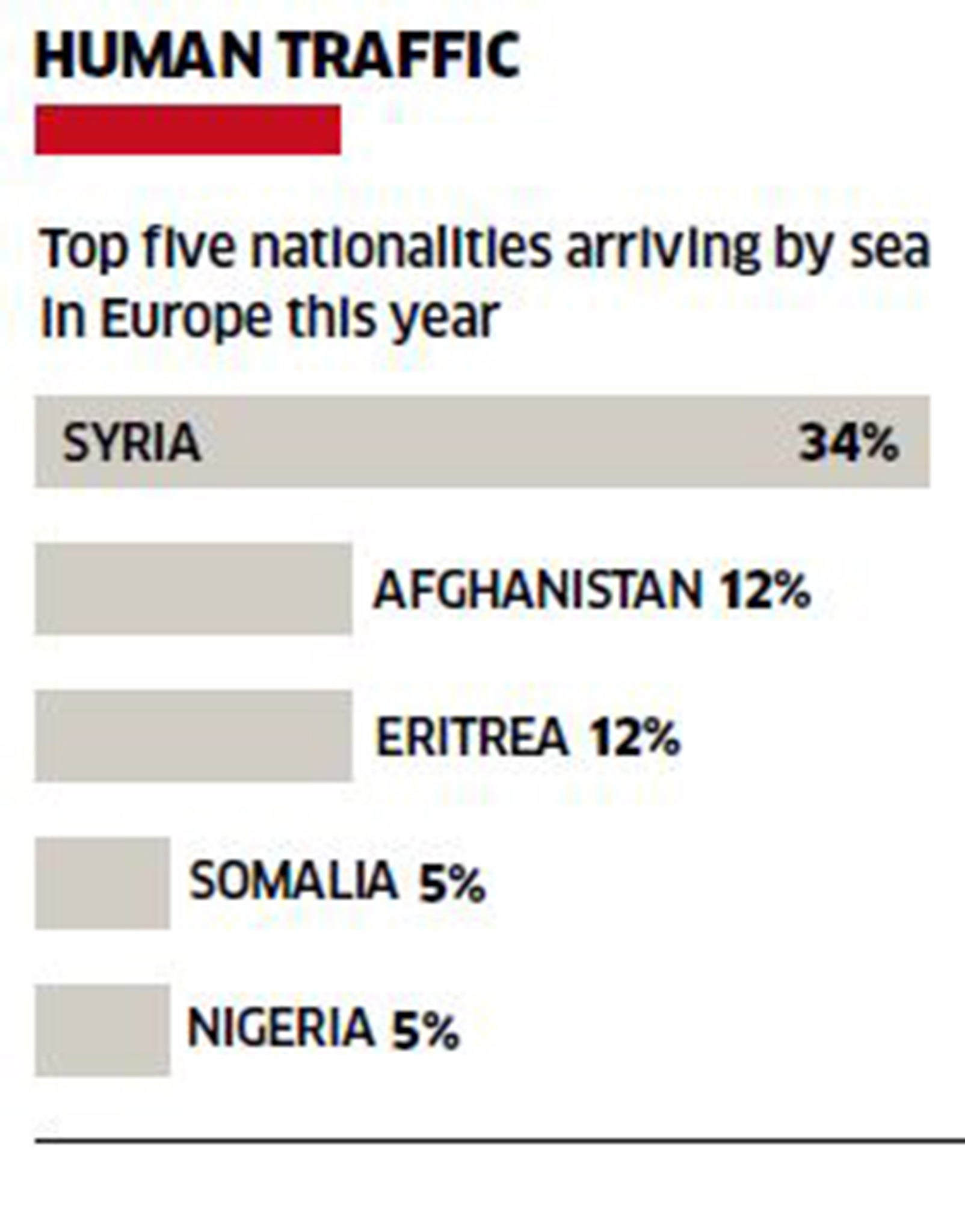

Abdulrahim Ali, 29, came from Eritrea in February and is living in Bradford after being granted asylum. A conscript, he spent eight years in the Eritrean army, before fleeing to Sudan and later Libya. He paid people-traffickers $4,000 to get to Italy, then travelled from Calais by hiding in a truck. “In the military, I was like a slave. When I went to Sudan, there was no escape as they can come into Sudan and take you back.

“When I arrived in Calais it was winter. It was really cold. I spent three months there. There was no food, no clothes. Some charities try to help. When I left Eritrea, I didn’t know anything about England or Germany or even where they were. Some people try to get asylum in France but are rejected.

“It is very good to be in the UK but it is not like heaven. I have come here to work. We are safe here. I have justice and freedom, but I miss my family, my wife and my land, and I hope to go back one day. More people know what is going on in Eritrea, and I have hope it will change.”

Dr Chefena Hailemariam is a former lecturer and lead researcher in Sociolinguistics in the English Department at the University of Asmara in Eritrea. He came to the UK seven years ago on a fellowship, and applied for refugee status after the political situation worsened in Eritrea and his university closed. He was granted asylum a month after applying. His wife and children joined him in Manchester three and a half years ago.

“It has been difficult to rebuild my career here. Although I had some associations with a few UK higher education institutions, there is a lot of skilled manpower in the UK and my field is extremely competitive. Also, connections are important. I do a combination of interpretation work and consulting and I keep up with research in my area of study.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments