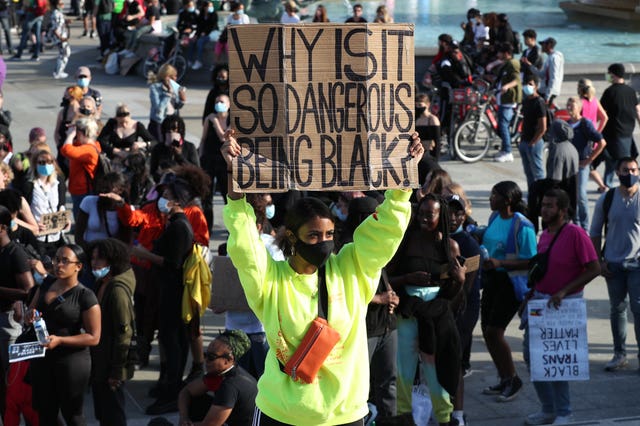

Black people are going missing in vast numbers - but campaigners say their cases are being ignored

Exclusive: Black people are four times more likely to be reported as missing in England and Wales - campaigners demand that this disparity is addressed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Black people continue to go missing across Britain in disproportionate numbers, campaigners say the government must do more to address the reasons – and that their relatives must stop being treated as merely a nuisance.

According to recent data from the National Crime Agency, Black people accounted for 14 per cent of missing people in England and Wales between 2019 and 2020, over four times (3 per cent) their relative population.

Though the agency does not currently have a breakdown in missing people by age, data shows that more Black men (13 per cent) went missing than Black women (10 per cent).

In London between 2019 and 2020, Black people accounted for 36 per cent of missing people, nearly three times their population in the city (13 per cent).

According to Sadia Ali, the founder of grassroots north London charity Minority Matters, which is largely devoted to supporting families whose children are trafficked by county lines gangs, the relatives of missing Black people acutely feel their lives are not given the same value as other lives.

“No life is worth more than the other and Black and ethnic minorities parents feel that their sons lives aren’t valued the same,” she said, speaking to The Independent.

And in recent weeks, two disappearances have again fuelled concerns that Black missing cases are taken less seriously than those of white people.

When Sarah Everard went missing at the beginning of March, having disappeared during a walk home in Clapham, south London, there was an outcry. Police issued appeals immediately and a widespread search ensued.

When her body was found a week later, and a Metropolitan Police officer charged with her murder, a vigil staged on Clapham Common was attended by the Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton. At this point, the matter was commented upon by the home secretary, Priti Patel, and Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

However, campaigners have argued that the response to Black people going missing is handled very differently.

Cases including Richard Okorogheye, Blessing Olusegun, Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman have attracted comparatively less attention. They were all Black, were all reported missing and, in all cases except one, the family members have accused the respective police forces of not taking their disappearances seriously.

Both in the police response, and the media reaction, the relatives of missing Black people report feeling neglected, or sidelined.

“We are concerned that some families from Black and other ethnic minority communities have told us that they have faced discrimination in the response from agencies when they have reported a loved one missing, and in the media coverage of their loved one’s disappearance,” a spokesperson from the Missing People’s charity told The Independent.

“We don’t know the full scale of this discrimination, and are committed to help make change happen, led by families with lived experience.”

Richard’s parents, Evidence Joel and Newton Okorogheye, have criticised the Met police’s handling of their son’s case, claiming that officers did not take their concerns “seriously” following his disappearance.

“I told a police officer that my son was missing, please help me find him, and she said, ‘If you can’t find your son, how do you expect police officers to find your son for you?’” Ms Joel said.

Speaking to The Independent on Thursday, Ms Joel also said the police appeared to be “counting the minutes” she was on the line, when she called for updates on his case. “‘Evidence, you have been on the phone for the last 10 minutes. We can’t give you any more information,’” she said they told her.

His body was found this week in Epping Forest, north of London. Ms Joel has said he seemed to be “struggling to cope” at university. While the home secretary has tweeted condolences to the teenager’s family, the prime minister has not publicly addressed the tragedy.

Similarly Mina Smallman, Nicole and Bibaa’s mother, claimed the police did not immediately respond to initial reports that her daughters were missing, adding that she had to personally coordinate a search operation on the weekend they died. The sisters’ bodies were then only discovered by Nicole’s boyfriend.

Ms Smallman said she believes that the police were slow to respond because her daughters were Black. “I think the notion of ‘all people matter’ is absolutely right, but it’s not true. Other people have more kudos in this world than people of colour,” Ms Smallman recently told the BBC. “My girls and Sarah (Everard) – they didn’t get the same support, the same outcry.”

The mother of Black student Joy Morgan, who went missing in 2019 and was later found murdered, told the BBC her case didn’t garner widespread attention: “Because my daughter was black and because I was black I was not newsworthy.”

But around the same time, Libby Squire, a white student of the same age, went missing and was also later found dead. Her case was a headline story, prominent across the national news for weeks.

One mother, who did not want to give her name, said there is a dangerous lack of awareness about the disparities in missing rates of Black people. Her son, who is mixed race, went missing at the age of 16, after being trafficked into county lines activity.

“All the focus has been on knife crime. The government should’ve done a big public information appeal about trafficking, highlighting the fact that Black boys are disproportionately more likely to go missing,” she told The Independent.

She wants schools to address the issue with their pupils, and said local authorities also need to do more. Public information campaigns need to give the issue the attention it deserves, she said.

“There should be adverts on television, regular missing appeals every month, billboards, information in schools; oftentimes children are going missing straight from the school gates.

“In America, Black children are more likely go missing. This a widely known fact, they appear to be more open about it but why is the disparity covered up here in the UK?

“It sounds awful but I think the only time that government minister will take this matter seriously is when one of their own children goes missing.”

The disparity is “another example of how Black people are over-policed as citizens, but under-policed as victims,” a Black Lives Matter spokesperson told The Independent. “The police are proactive in criminalising our communities, but when it comes to keeping us safe, more often than not, they are not fit for purpose.”

“The media and authorities have time and time again demonstrated a lack of action when it comes to Black missing persons cases.

“The media has dedicated years of coverage to the story of Madeleine McCann, and the police have spent nearly £12m on ‘Operation Grange’, in the hopes of finding her. Meanwhile, few members of the British public have heard of Aamina Khan or Elizabeth Ogungbayibi. All disappearances and deaths are tragic – yet the media and the police do not treat them as if they are.”

Aamina Khan vanished from south London in 2011, aged 6, and was thought to have been kidnapped by her mother, while in custody of her father, and taken to Pakistan.

Elizabeth Ogungbayibi has been on Greater Manchester Police’s missing persons list for more than a decade after going missing in 2006, aged 5.

“In the face of structurally racist policing and media, we must continue to look out for each other.”

For Ali, at Minority Matters, negative experiences with the police can often then discourage parents from reporting their teenage children missing.

“Black parents or ethnic minority background parents give up going to the police following their first negative experience or what they have seen happening to other parents. He’s over 18 and free to go, is the regular response.”

The majority of London’s missing children and young people are lost to “to county lines and criminals exploiting them to sell and transport drugs,” she said. “They are very young and too scared to say no, often exposed to mental and physical abuse until they fully submit. Parents are unaware during the first months, years and suddenly they go missing, this being out of character.

But that is just one reason, and she added, “Black children and young people can be missing for other reasons such as mental health, addiction to drugs or choosing different ways of life or cultures that their parents won’t approve of.”

A National Crime Agency spokesperson said: “Individuals from some ethnic minority groups remain over-represented among missing persons reports. While those who go missing can be driven to do so by individual circumstances, UK Missing Persons Unit initiated work with academia in late 2020 in order to seek an increased understanding of the potential reasons for minority over-representation.

“This work will remain ongoing throughout 2021.”

The Home Office and Metropolitan Police has been approached for comment.

The Samaritans are a charity available 24 hours a day offering a confidential listening service to anyone in distress. To contact the Samaritans helpline, call 116 123. The phone line is open 24 hours, seven days a week.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments