Battle of Hastings: Site of 'sequel' fight between sons of King Harold and the Normans tracked down to north Devon

The follow-up battle in 1069 tracked to a quiet valley between Devonshire towns of Appledore and Northam

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

When he was a small boy, Nick Arnold’s grandfather entertained him with stories of a gory medieval battle between Vikings and Saxons which had, according to local legend, taken place close to his home in the north Devon countryside.

Fate took Mr Arnold down the path of a career as a successful children’s science writer but he never forgot his grandfather’s tales and his decision to investigate the reality behind the folklore looks set to change the understanding of English history.

After five years of research, the author of the popular Horrible Science series has pinpointed for the first time the site of the battle as an encounter not between rampaging Vikings and Saxons but the decisive clash in the fight for control of England started by the Battle of Hastings.

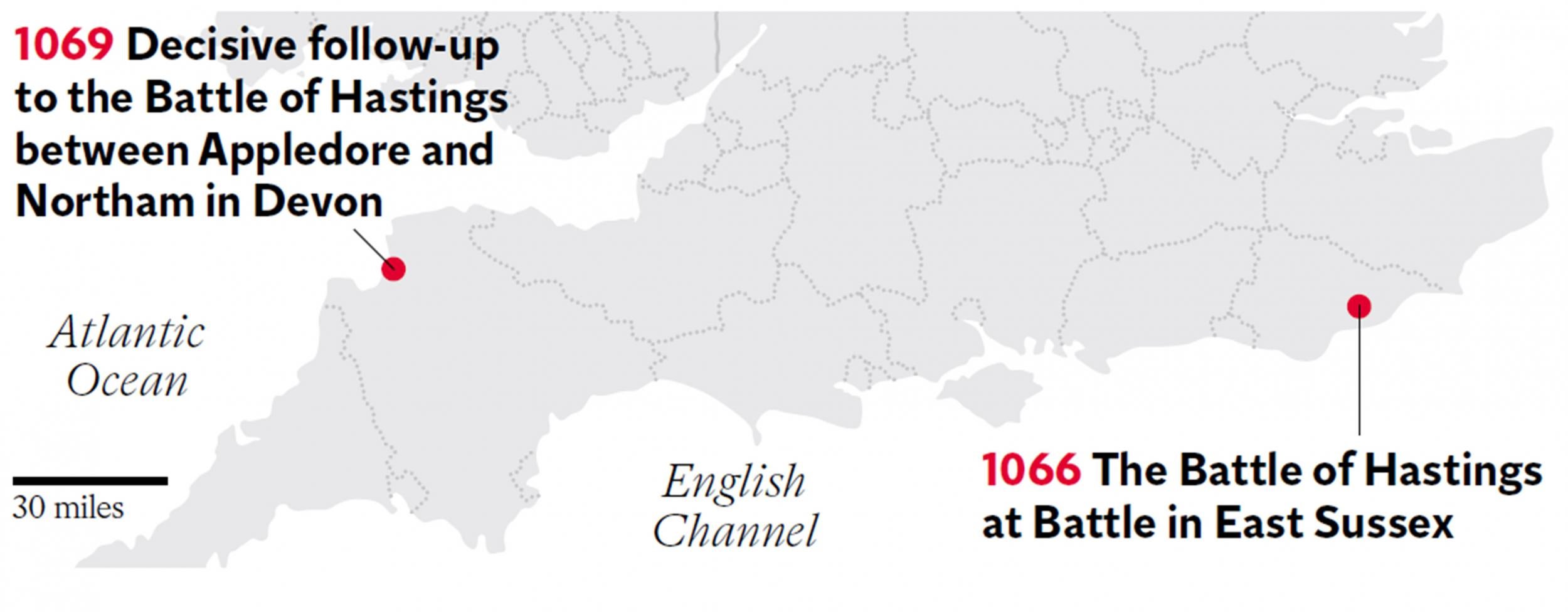

A “sequel” to the confrontation which left King Harold dead at the hands of William the Conqueror’s Norman army in 1066 has been tracked by Mr Arnold to a quiet valley between the Devonshire towns of Appledore and Northam.

Academics have described the finding as a “significant” breakthrough in English medieval history.

The battle, fought three years after William I was installed as King of England, took place after Harold’s two bereaved and vengeful sons - Edmund and Godwine - raised an army in Ireland and sailed to the north Devon coast on 64 longships with the intention of claiming back the throne from the Norman invader.

It was not to be. The Anglo-Saxon and Irish force was seemingly surprised by a waiting Norman and English army, resulting in a nine-hour Battle of Northam which left 3,000 dead and the invasion force routed.

Mr Arnold, who despite his work in explaining science is a historian by training, managed to locate the battlefield via a painstaking process of comparing contemporary accounts of the battle with maps and data to calculate the time of dusk and the tides on the date of the clash - 26 June 1069.

A combination of factors, including the fact that sunset and the high tide coincided on that day, led to the author to conclude that the battle could only have taken place within a few minutes of Godwine and Edmund’s landing place at Appledore.

Mr Arnold said: “It’s been like a piece of detective work. Once you arrive at the conclusion that the battle must have taken place between Northam and Appledore you have to look at the terrain to see where the fighting could have taken place. In the end there was only one possibility, a rather picturesque valley which miraculously hasn’t been built on.

“Inside me is the child who listened to my grandfather and always wanted to be a historian. Now that dream has come true and I think it changes the way we look at this period. It wasn’t until this battle that the Norman conquest was secured and if Harold’s sons had won it would have changed English history by cutting short French influence from Normandy.”

The author, whose research has been peer reviewed by early medieval historians and is to be re-published by the Battlefields Trust, is now calling for the site close to Northam to be granted protected status and further researched with the possibility of archaeological excavation.

Benjamin Hudson, professor of medieval history at Pennsylvania State University, hailed the research as a “significant contribution to the history of medieval Britain”.

Mr Arnold said: “I think my grandfather would have been absolutely thrilled to know that there was something in his stories.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments