Barbarians at gates of Lord Beaverbrook's 'chateau'

The press baron's home is to become Britain's most elitist golf club but locals are cutting up rough

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a fight that Lord Beaverbrook, that fearsome newspaper tycoon, would have relished. On one side, millionaire developers with a plan to transform his former home in Surrey home i nto a hotel, spa and exclusive 18-hole golf course. Set against them were the National Trust, environmentalists, and residents suspicious that their views would be ruined.

Planning permission was granted in May, but an appeal against the decision was referred to Eric Pickles, Secretary of State for Community. Yesterday, a spokesman for Mr Pickles told the developers, Longshot, there was insufficient reason for him to intervene, meaning the development will go ahead.

Cherkley Court is an imposing wedding-cake of a house built in 1866 by a Birmingham businessman called Dixon, and rebuilt in the French chateau-style in the 1890s. It stands in a 380-acre estate in Leatherhead, with 120 acres of woodland. The conversion of house and grounds to incorporate a hotel, two restaurants, a spa, a herb kitchen and cooking school is expected to cost £60m, and employ 200 people. Membership of the golf course will be limited to 500, who must put up £100,000 each.

It was a development always guaranteed to raise the hackles of environmentally-friendly anti-capitalists. But Longshot, whose acquisitions have included London's Groucho Club, attempted a smart public relations game. When the Court was put up for sale by the Beaverbrook Foundation in 2010 the partners, Joel Cadbury and Ollie Vigors, launched a charm offensive. They invited the Leatherhead locals to tea in the Orangery to show their plans for the house in glossy detail. "We didn't need their permission," said Vigors. "We already had the consent of the Foundation. But we wanted to know there was local support."

Unluckily, the tea party flushed out some vocal opponents. Jonathan Kenworthy, a former protégé of Lord Beaverbrook, and his wife Kristine had access rights to their house through the estate. At the presentation, they said they didn't want a golf course obscuring their view. "From that day," said Vigors, "they've done their best to galvanise support against the plan."

Among the objectors were Mole Valley District Council, the National Trust and the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE). Their concern is that part of the Court's grounds lie inside the Surrey Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, while the whole area is within the Green Belt; it's feared the golf course could spoil the landscape, and harm the grassland and woodland. "If this is passed, "No heritage site will be safe," said Caroline Brown of the Leatherhead Residents' Association. "Do we need another golf course?" asked Tim Harrold, vice-president of the Surrey CPRE. "We already have 140 in Surrey."

In response, the people at Longshot launched a campaign. A fake newspaper, The Cherkley Express, was sent to 9,000 local people. The support of the golfing titans Tom Watson and Colin Montgomerie was solicited. A radio debate voted 60 per cent in its favour.

The opponents hit back. Jodie Kidd and Michael Caine were quoted as opposing the plan, but both later retracted (Ms Kidd is a descendant of Lord Beaverbrook). Committee hearings in May were followed by complaints with a faintly desperate ring. Someone discovered that a Mole Valley District councillor was related to Joel Cadbury. Accusations flew of an "inappropriate relationship" between the same councillor and Nick Kilby, Longshot's communications consultant, because he had re-tweeted someone else's compliments to her.

Now that Longshot has won, Joel Cadbury is keen to stress the positive. "The most important point has been the overwhelming support of the local community. It's a mystery why this small but vocal group should feel so negative about a plan to restore the house to its former glory, to reinvigorate the estate and to create employment in the local community."

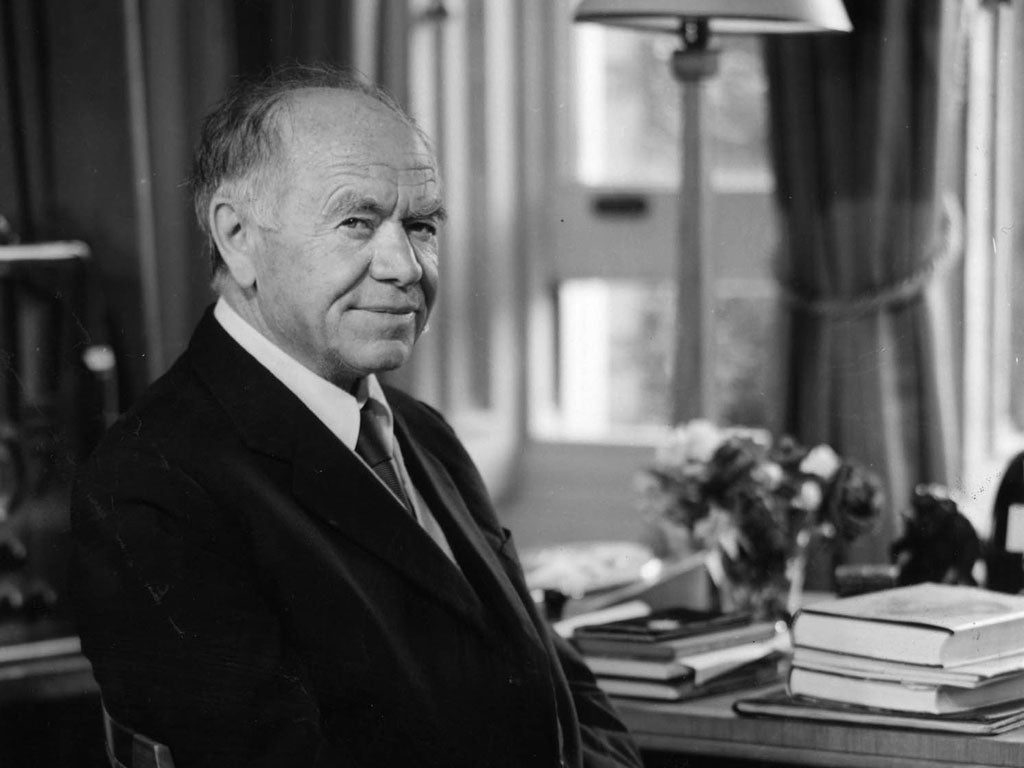

William Maxwell Aitken, the first Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian newspaper magnate who became one of Winston Churchill's closest friends and served as a cabinet minister in both world wars. A wily and manipulative powerbroker, he set up the Express Newspaper Group and changed the face of the popular press. He owned Cherkley Court for 50 years, willing it to his son in 1960, four years before he died.

He bought it in 1911. Driving from Rottingdean to London with Rudyard Kipling and his wife, he spotted a "For Sale" sign, and bought the house for £30,000 after a single inspection. His biographer, A J P Taylor, called the Court "a harsh square block of a house" with "no architectural merit". Beaverbrook's friends told him it was "an overgrown suburban villa rather than a country house". There was no electricity or central heating or, indeed, running water. But Beaverbrook liked it. He spent £10,000 on renovations, installing a swimming pool a tennis court and later an Art Deco cinema where he regaled guests with Westerns and Marx Brothers films.

The library was the scene of many political intrigues. It was there that Bonar Law agreed to allow Lloyd George to run the War Office, in 1916. In 1922, just after the Irish Free State was established, its first Governor General, Tim Healy, came to dinner at Cherkley and met H G Wells. Churchill, Chamberlain and Lloyd George met there to discuss how to supplant Stanley Baldwin's coalition government – but another guest, Arnold Bennett, leaked their discussion to the newspapers and Labour won the next election.

Michael Foot, a Beaverbrook journalist and later Labour Party leader, was a frequent visitor. It's believed that the Court was used by the Cabinet was an alternative war bunker, and that Churchill used to fly in for war discussions – the prime ministerial plane landing on what, barring any more turmoil, will soon be the fairway.

Cherkley Court: Haunt of the elite

Cherkley Court in Surrey was a hub for society's elite in the first half of the 20th century. Leading political and literary figures could regularly be spotted in the corridors of the mansion, bought by Lord Beaverbrook in 1910.

During the 50 years the magnate owned the estate, Winston Churchill spent so much time there that he was given his own room, while H G Wells and Rebecca West were regular guests. Lord Beaverbrook's family inherited the estate after his death but when Lady Beaverbrook died it was bought by the Beaverbrook Foundation, and opened to the public. Falling visitor numbers led to its closure and in 2010 it went on sale with an asking price of £20m.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments