Why this great betrayal of Britain’s nuclear bomb veterans could be the next Post Office scandal

Reckless exposure to atomic weapons during the nuclear arms race left veterans’ lives blighted with debilitating health conditions that have ravaged generations of their families. Zoë Beaty reports on their decades-long fight for justice

For John Folkes, it all began with a simple command, and a blinding flash. It was September 1956, and he was flying 18,000ft over Maralinga, Australia, secured in his seat by a single lap and shoulder strap, when a 15 kiloton atomic device – as powerful as the weapon that had devastated Hiroshima a decade before – was detonated over the desert plains below.

Two days earlier, the 19-year-old had been told that his job was to head directly into the mushroom cloud and collect a sample of the radiation released by the blast. The flash blazed beneath him, forming an image that would terrorise Folkes’s dreams for the remainder of his life: it was “an inferno”, he recalls, describing “crimson and black smoke billowing up towards us”. “The cloud was rising, it was coming up faster than we expected, but there was no turning round, no brakes on a plane. That’s when I thought ‘We’re not going to make it.’”

They sped up. Suddenly, all the gauges in the cockpit were spinning out of control. Folkes shared a look with the pilot. “No more than four seconds later, we were hit with this enormous shockwave, which flipped the aircraft over on its back, leaving me suspended in the air on these straps.”

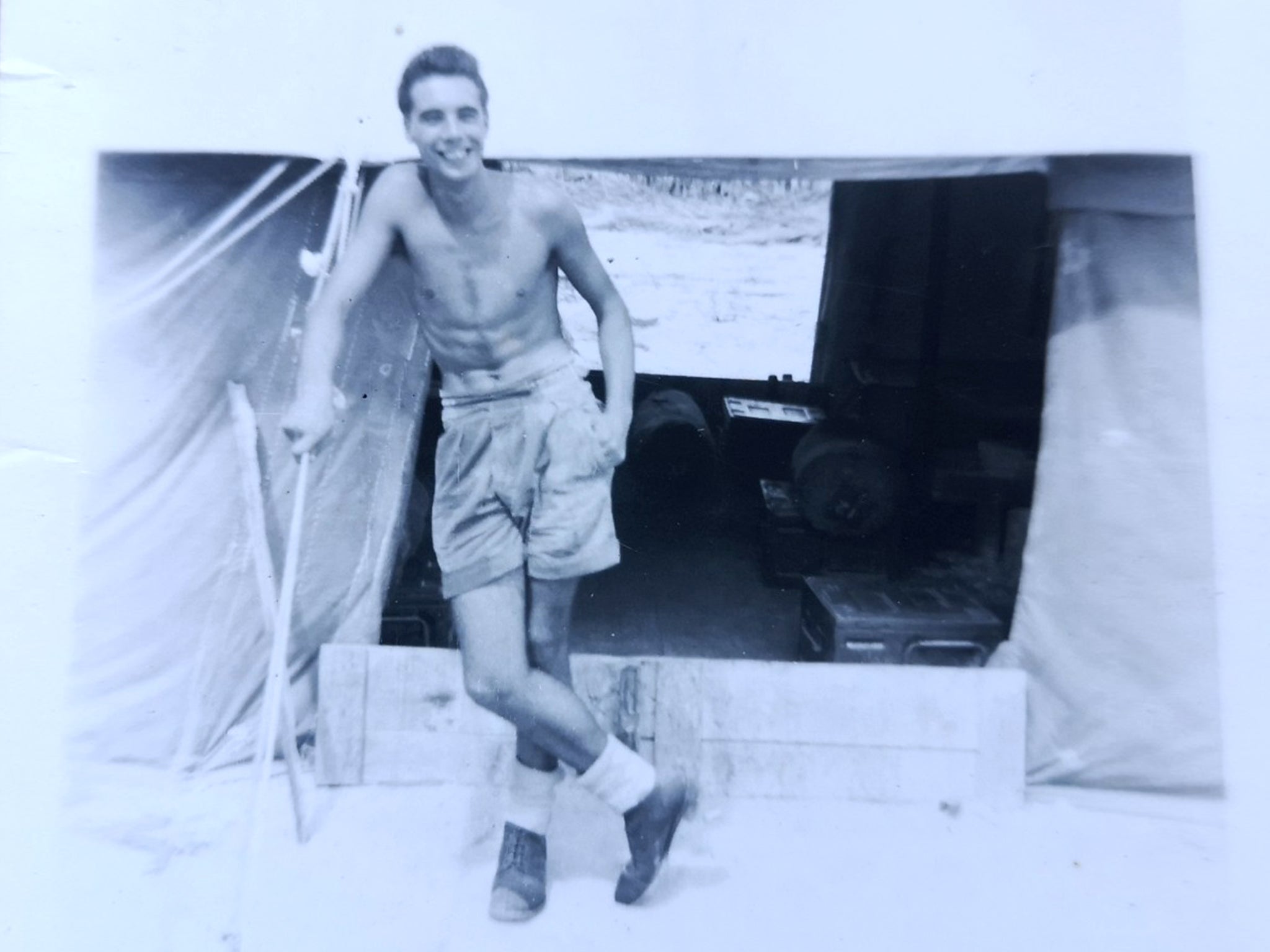

Unfathomably, they made it safely to the ground – “By the hand of God,” says Folkes, who is now 89 and lives in Thanet. The moment he stepped off the plane, his hands began violently shaking, and they haven’t stopped since.

Folkes was working as part of Operation Buffalo, carried out by the UK’s Atomic Weapons Establishment. He was just one of thousands of young men whose lives were treated as little more than collateral damage in Britain’s race to become a global nuclear power.

In the years that followed the Second World War, the nuclear weapons programme placed 39,000 service personnel, scientists and local people in close proximity to 45 nuclear bomb detonations and hundreds of radioactive experiments. The testing left a permanent mark on once-pristine areas such as Maralinga and Christmas Island, causing lethal contamination to regions inhabited by Indigenous Aboriginal and Gilbertese populations. Many of those who were exposed to the blasts experienced debilitating illness for the rest of their lives, with the after-effects of the radiation affecting generations of their families.

They weren’t respected servicemen, they say, but disposable pawns in a deadly game. Large swathes of the men developed cancer – commonly of the liver, blood, bone, bowel, skin or brain – and overwhelmingly high numbers of families suffered stillbirths, generational birth defects, and miscarriage.

Despite this, they’ve been consistently denied compensation from the War Pension Scheme (WPS). The proof that they were harmed, they allege, has been covered up for decades by the Ministry of Defence. For years, atomic programme veterans have repeatedly requested blood test results and other medical records, only to be told that no such tests were carried out.

Numerous FOI requests made by Daily Mirror journalist Susie Boniface revealed the existence of more than 4,000 top-secret documents relating to orders to conduct medical examinations on thousands of troops and civilians – documents that have been hidden ever since. Raw blood test data obtained by Boniface stands as evidence that MoD officials were misleading government ministers by denying that this testing had ever taken place.

The veterans’ decades-long fight for justice has been rightly likened to the Post Office scandal. It’s only now that a different story is beginning to emerge, one that will be exposed in a new BBC documentary, Britain’s Nuclear Bomb Scandal: Our Story, next week.

“I was invited to a seminar in 2022; it was with a lot of the nuclear veterans and their family members,” John Morris, 87, from Rochdale, explains. He was posted to Christmas Island aged 18, having never travelled further than Blackpool before. “There were 12 men on that stage, and we were asked a question – ‘Have any of you lost a child?’ All 12 men put their hands up. Alongside them, 11 women got on the stage, who were asked, ‘Have you lost a child, or had a deformed child, or miscarriages?’ Again, every single one put their hands up. This is a story that resonates with hundreds of veterans’ families. It’s just not right.”

While serving, Morris was instructed to sit on the ground with his back to an exploding nuclear bomb 20 miles away. “Boys next to me were wetting themselves, others were praying. Some wanted their mothers,” he recalls. They were given shorts, T-shirts and sunglasses as their only protection. “There was a countdown,” he explains. “We put our hands over our eyes. When the bomb went off, the light was so bright, I can’t begin to explain it. Like nothing you’ve seen before.

“It was so bright that I could see through my hands – literally through them, the bones, the blood. I felt my blood boiling, like I was being microwaved. The heat was immense. The palm trees were all scorched, the iron wagons were so hot we couldn’t touch them for hours. The wiper blades had all been melted... In those two minutes, I was exposed to millions of X-rays. And then, everything was contaminated by the cloud.”

Morris, who has had pernicious anaemia since his twenties and later developed prostate cancer, had a son, Steven, with his wife not long after he returned from duty. He was a happy little boy, and family life came easily to the couple. “We were very proud,” says Morris. “One night we put him to bed in the normal way, having fed him, and my wife woke up in the middle of the night to find Steven dead in his cot. She was beside herself and ran up to the telephone box to call an ambulance, while I tried to give him the kiss of life.”

Steven was pronounced dead at the hospital – and Morris and his wife were initially arrested for his murder. A coroner later ruled that Steven had died of pneumonia, and the allegations were dropped – but Morris felt his diagnosis was incorrect. Only in the last couple of years was he able to track down a copy of Steven’s autopsy report, which showed he had underdeveloped lungs. Morris believes this was likely to have been caused by his exposure to radiation.

“Before she died, my wife always felt I was responsible for Steven’s death,” Morris explains, his voice cracking with emotion. They had two more children, whom Morris regimentally checked on each morning and through the night. “I am now a great-grandad. [My great-grandson] is eight weeks old now, and I am terrified in case he dies or there’s something wrong with him. That fear is always there. It will always be there.”

For Steve Purse, the fear of passing on genetic abnormalities – his father, David, served in radioactive experiments known as “the minor trials” in Maralinga in 1963 – almost stopped him from having children altogether. Purse was born with a number of disabilities, including a unique form of short stature.

Purse’s father told him that he had watched officials try to simulate crashes of aircraft carrying nuclear weapons – “Basically, piling explosives onto warheads to see what it would take to make them pop,” he says. “He described watching molten jets of plutonium squirting 200ft in the air. It went everywhere – the wind carried it. They said they cleared it up, decontaminated it. But you can’t. The wind blows it, and you don’t know where.”

When Purse met his wife, they decided to roll the dice – and later welcomed a gorgeous baby boy. He seemed healthy, but, as he’s grown, Purse says, it’s become clear that “he hasn’t escaped”. Now three, his son has a genetic condition that means his teeth are crumbling. “I hope that’s all he’ll get. But that’s the nature of what we deal with. It’s invisible bullets being fired.”

Like hundreds of others, Purse continues to campaign for justice for his dad, and for other veterans who have been consistently dismissed by the MoD, denied recognition for their service, and denied the compensation they’re entitled to.

Morris has taken his fight to every corner he can find. Now, he is calling for Keir Starmer and Angela Rayner, who pledged to help the veterans while in opposition, to make good on their promise.

The veterans want a public apology, and for what they’ve been through – the sacrifices they’ve made, and the fear they’ve lived with since – to be recognised. “Our next step is to take the MoD to court,” says Morris.

Folkes, who has complex PTSD and is plagued by nightmares that he’s “falling out of the sky”, explains that many veterans were unable to speak out until recently because they had signed a 50-year embargo under the Official Secrets Act.

He called his book about his experiences Silent Tears. “That is because so many veterans have died as a consequence of this. They must be in their thousands. And there are copious deformities, and lost children, and children who are going to have problems in the future.

“It has been a big problem, and it continues to be. I find it very difficult that our government is still trying to hide it. It’s time for answers.”

‘Britain’s Nuclear Bomb Scandal: Our Story’ is on Wednesday 20 November at 9pm on BBC Two and on iPlayer

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments