Ten years ago we predicted how 2020 would turn out. From Boris as PM to the climate crisis, here’s what we got right and wrong

Four Independent writers look back at the newspaper’s 2010 predictions for how the world would look now, and see how right - or wrong - we were

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2010, 10 of The Independent writers and editors wrote their predictions for the next decade.

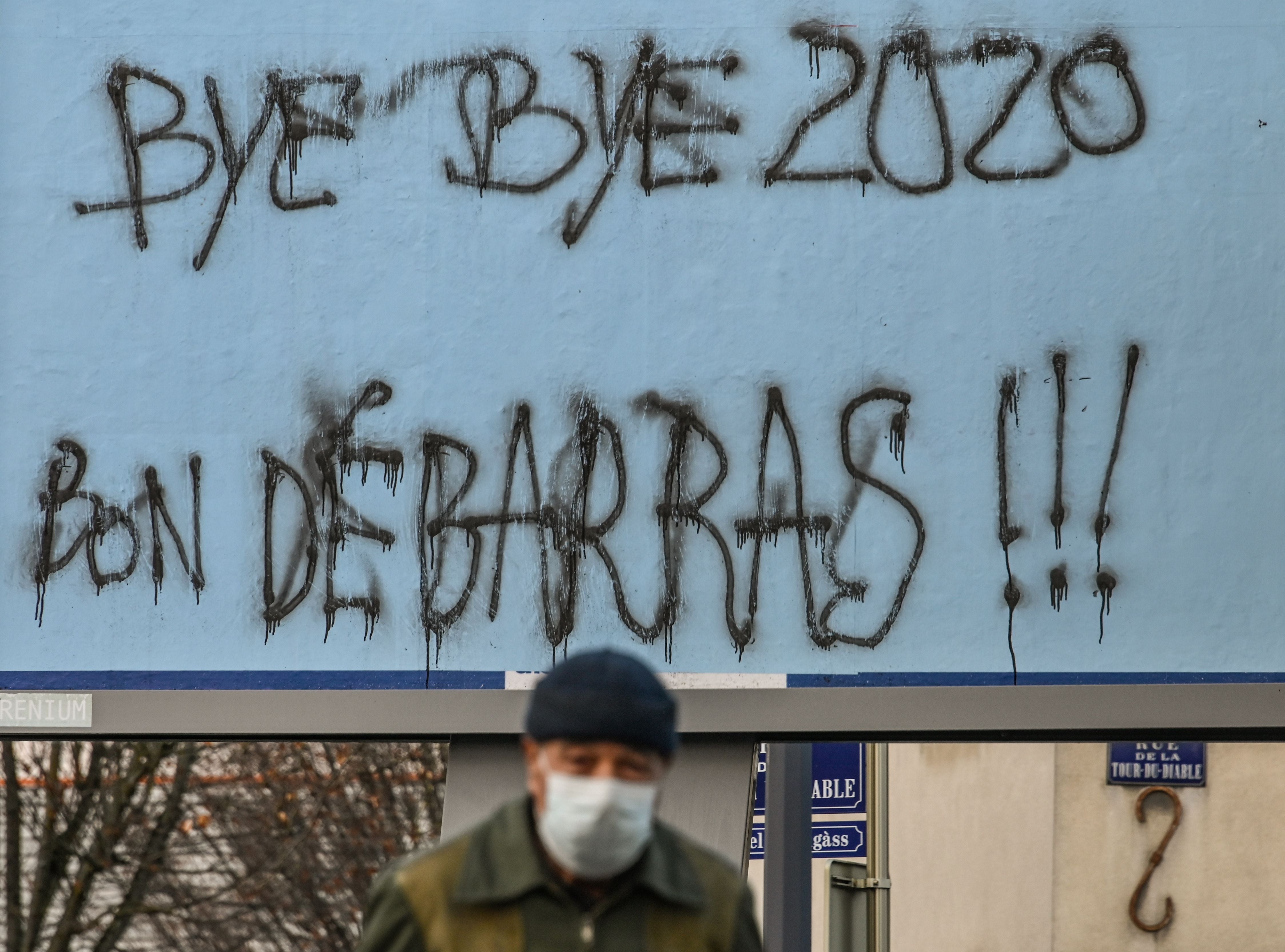

Whilst 2020 may feel like a decade in itself, as we look to the 20s, today’s Independent team reflect on how accurate those predictions – Boris Johnson as prime minister! – were. And all those things – from Brexit to a certain pandemic – that we missed…

Read the original predictions here:

The world in 2020: A glimpse into the future

The world in 2020: Thrift, hard work, and no smoking

Climate Correspondent Daisy Dunne on Michael McCarthy’s predictions for the natural world in 2020

“An atmosphere with more heat, moisture and energy in it could lead only to one thing: a more unpredictable global climate with severe heatwaves and droughts, more intense rainfall with subsequent flooding, and more violent storms. And so it did.”

These are the words written by the great Michael McCarthy, The Independent’s former environment editor, in 2009 when he was asked to speculate what the natural world might be like by 2020.

His prediction certainly rings true today. A report released in November found 1.7 billion people – one in five of the world’s population – were affected by extreme weather events in the past decade.

Though not every extreme weather event is caused by the climate crisis, a growing body of research suggests human-caused heating is making many types of extreme weather events more likely and more severe. The “fingerprint” of the climate crisis has so far been detected on heatwaves, hurricanes, droughts, wildfires, floods and episodes of extreme glacier loss.

For example, a study published in July found this year’s record-breaking Arctic heatwave was made 600 times more likely as a result of the climate crisis. Further research has shown that 2018’s northern hemisphere heatwave would have been “impossible” without the climate crisis.

“Halfway through the new decade, people began to accept that the UK was warmer,” Mr McCarthy continues.

“It marked a victory for the Met Office's Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research, which had published a climate forecast for the years 2009-2019 at the end of the previous decade, suggesting that more than half of these 10 years would be ‘hotter than the hottest year’ on record. It had already been proved right by predicting that 2010 would surpass 1998 in terms of temperature and set a new global record.”

The Independent is not far off with this prediction either. Met Office analysis shows the decade 2010-19 saw eight new UK temperature records, including both the highest winter and summer temperatures seen in the country.

Overall, the 2010s have been the second hottest of the “cardinal” decades – those spanning years ending 0-9 – over the last 100 years of UK weather records, the Met Office says.

The Independent also predicted that “in 2016, a heatwave hit southern England with temperatures of 40C (104F), prompting a mass exodus to the country's parks every weekend”.

The UK has not yet seen temperatures of 40C, though Met Office research shows the risks of this happening before the end of the century are rapidly increasing.

However, during last year’s summer heatwave, a new UK-wide temperature record of 38.7C was set in July at the Cambridge University Botanic Garden.

Another one of The Independent’s predictions was that “the first definite marker of a warmer world which made people sit up and take note was the first serious shark attack on a swimmer off the British coast in 2014”.

“As had been predicted during the previous decade, as seas across the world warmed, marine life migrated northwards. Scientists were soon forced to admit that sightings of the great white shark – Carcharodon carcharias, the protagonist of Jaws, and the marine creature most dangerous to people – would soon become a regular occurrence off the UK,” writes Mr McCarthy.

Despite what recurrent tabloid headlines would have you believe, the climate crisis has not led to a substantial increase in shark attacks in UK waters.

Sea temperatures have increased, leading to an overall poleward shift for many marine species, as predicted by The Independent. However, this hasn’t led to shark species from the tropics moving closer to the UK.

One reason why great white sharks and other similar species have not moved in around the UK is because there is no suitable food source for them here, scientists previously told the climate website Carbon Brief.

Associate Editor Sean O’Grady on his own predictions for society one decade on

It’s never a bad idea to look back. For most of us, most of the time it brings the great benefit of an enhanced sense of humility.

Well, maybe I should speak for myself, because I pretty much got everything about the economy in the 2010s way wrong. Obviously, I missed seeing Brexit coming, not that unusual maybe, but I was one of those who wondered whether it might successive, and inter-related, banking, sovereign debt and euro crises.

I wasn’t much less pessimistic about Britain’s prospects. After the trauma of the collapse and rescue of the banks, the Great Recession and the dawning of the age of austerity it seemed reasonable to assume a decade of slow growth and big national debt. I was right there, but wrong to think it would provoke strikes and general unrest as various sections of the population attempted to retain their share of the shrinking pie of prosperity. Britain was stagnant, but people seemed not to care. Presumably, this was because their anger was redirected from the usual class-based conflict towards immigrants, the European Union and into “culture wars” as a proxy for the economic warfare that “ought” to have emerged.

More widely, and more optimistically, I was too downbeat about the economy (poor as growth has been) and underestimated Britain’s resilience. It was certainly inevitable that the country’s credit rating would suffer under the burden of debt (even pre-Brexit and pre-Covid), but what is remarkable is that Britain has been able to borrow and “print money” at ultra-low interest rates and low inflation. I suspect that may not persist though.

But that British economic resilience is a striking long-term feature. Not to be confused with economic success – that has varied – but the avoidance of abject failure and collapse even after crises and seemingly intractable problems. Even excluding the two world wars, when the nation over-mortgaged itself, the country has survived long bouts of apparently endemic mass unemployment, rampant inflation, sterling devaluations and a permanent addiction to debt. Restructuring and recovery have always arrived, and the economy has adjusted to its shocks. Many of us thought Britain couldn’t escape the grip of trade union power in the 1970s, Thatcherism in the 1980s or indeed the austerity of the 2010s – but they passed and things improved.

Looking forward, the first decade of Brexit (assuming it is not reversed), will very likely follow that pattern of slump and surprising recovery. I might be wrong, though.

Home Affairs correspondent Lizzie Dearden on Mark Hughes’ predictions for the decade

A decade ago, crime correspondent Mark Hughes forecast that in 2020 we would become “one nation under CCTV”.

He forecast that the number of cameras in the UK would rocket, and that they would start listening in on conversations.

The truth is that while few CCTV cameras in public spaces record sound, the same cannot be said for the unknown number of private surveillance systems purchased by the public.

The plummeting cost of video doorbells and security kits that can be monitored using the owner’s mobile phone has seen a dramatic increase in the devices, which do not need to be registered.

Research by the CCTV.co.uk industry group estimated that 96 per cent of around 5.2 million cameras in the UK are operated by homeowners and private businesses, rather than public authorities and councils.

The footage captured has been used in criminal cases over burglary, theft, and even a far-right terror attack.

So while you might not be listened to by the CCTV camera staring down at you at the local train station, your neighbours might be able to catch your conversation as you walk past their front door.

Perhaps the biggest change in camera surveillance has been the rise in live facial recognition, which allows police and – increasingly – private companies, to automatically look for matches between passers-by and watch lists.

Two British police forces, in London and South Wales, started deploying the technology in crowded spaces, saying it would help spot wanted violent criminals and potential terrorists.

But they were swiftly hit with legal challenges over alleged human rights violations, while the effectiveness of facial recognition has also been questioned.

Mr Hughes can be forgiven for failing to predict the invention of such technology, having accurately foreseen the rise in cyber-crime and online fraud.

His prediction that even drug dealing would primarily be conducted over the internet did not come to fruition, as the decade instead saw the rise of brutal “county lines” model.

It sees gangs send drugs from urban centres to smaller towns and rural communities using children and vulnerable people as couriers, while using threats, violence and coercion to take over people’s homes as bases.

Who would have predicted that in an age of such rapid technological advance, drug dealing would revert to methods so exploitative that they are considered a form of modern slavery?

Mr Hughes made a series of optimistic projections that sadly did not come to pass, such as the declining theft of personal belongings and cars due to technological advances.

He also thought the conviction rates for serious crimes would rise following the combination of the 43 police forces in England and Wales into a super-force with multiple specialist units.

The idea is still sporadically discussed, but there is little political appetite for change from the Conservatives, who were responsible for introducing elected police and crime commissioners for each force.

In fact, prosecution rates for all crimes have fallen to record lows of just 7 per cent in England and Wales, with rape standing at just 1.4 per cent.

Police and criminal justice agencies blame the cumulative impact of austerity for the dire statistics, following the loss of 20,000 police officers and cuts to the Crown Prosecution Service, amid increasingly complex crimes and large amounts of digital evidence.

Coronavirus initially caused a sharp drop in crime, but the mounting court backlogs that followed are likely to have a long-term impact, amid fears that anxious victims will drop out of prosecutions.

The effect of the pandemic on crime and justice, as well as other aspects of our daily lives, may come to define the next decade.

Chief political commentator John Rentoul on the politics of the decade

In the 2020 general election, the party leaders “set themselves an exhausting schedule of public meetings”, speaking face-to-face to live audiences, because young people, sick of digital communication, “are unwilling to vote for anyone they have not seen or heard in person”. That is how my colleague Andy McSmith imagined the future 10 years ago.

How the gods mock such predictions! I’m so glad it was Andy rather than me who was given the task of failing to foresee a virus pandemic that would render in-person politics a distant memory for those of us who lived through the real 2020.

How quaint it seems, too, that Andy assumed – even before the Fixed-term Parliaments Act – that elections would happen every five years. He was writing before the 2010 election, which was about to take place five years after the previous contest in 2005. The 2015 election took place on schedule, but instead of a “surprise defeat of David Cameron’s government”, it resulted in a surprise win – and the eclipse of the Liberal Democrats, who had not even featured in our imagined future.

So Peter Mandelson did not lead Labour back to power after all, which is a shame. And the entire sequence of Britain leaving the EU, which dominated the second half of the decade in real life, was absent from the fantasy timeline. One referendum and two more elections took the country in a direction that seemed scarcely possible 10 years ago.

Yet Andy got some striking things right. He predicted Boris Johnson would be Conservative leader in 2020, although he cannot have imagined the corkscrew route that would take him there.

He also thought that Vladimir Putin and Angela Merkel would still be around. And you could see how he was on the right lines in imagining Arnold Schwarzenegger as US president – he couldn’t have been, having been born outside the US, but he is an ageing celebrity.

Andy ended his forecast on a quirky note. He thought blogging would be making a comeback, despite being seen as a “middle-aged obsession”, and that bloggers would be leading a “lively online campaign” to increase MPs’ pay and allowances. For those of us who believe in the essential virtue of democratic politics, it was comforting to imagine that there might be a backlash against some of the more extreme hatred of politicians unleashed by the MPs’ expenses scandal of 2009, but it was not to be. Andy thought that in 2020, “British MPs are now the least corrupt, most highly respected, and lowest paid of any Western democracy”.

Sadly, real politics went in a rather different direction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments