Life in post-First World War Britain revealed as 1921 census is released

Historian David Olusoga said the survey captured ‘one of the most dramatic and dangerous moments in history’.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The lives of every man, woman and child living in England and Wales in 1921 have been revealed like never before, with detailed census returns from Windsor Castle and Chequers to cramped family homes made available to the public for the first time.

The records, released after 100 years locked in the vaults, offer an unprecedented snapshot of life across the two nations, capturing the personal details of 38 million people on June 19 1921.

The census features a number of famous names and their families, including the prime minister David Lloyd George and King George V, as well as one-year-old Thomas Moore – who would find fame a century later as NHS fundraiser Captain Sir Tom.

It also shines a light on the grim reality of post-First World War Britain, amid crippling unemployment and social unrest, a changing jobs market, and a shortage of suitable housing leaving whole families packed into one-bedroom properties.

Historian and broadcaster professor David Olusoga told the PA news agency: “I think it shows a snapshot of a country in absolute trauma, a country in the midst of trying to recover from what was the biggest rupture in its history.

“It captures one of the most dramatic and dangerous moments.”

Among those whose census return underlined the hardship suffered by the working classes was James Bartley, a father of three young children from Sussex, who wrote: “Stop talking about your homes for heroes and start building some houses and let them at a rent a working man can afford to pay.”

Retired Army officer Harold Orpen, 46, originally from London, apologised to census officials for providing a typed response rather than the required handwritten one, adding: “I lost half my right hand in the late war and cannot write properly.”

Alice Underwood, 53, from Buckinghamshire, was more forthright.

“What a wicked waste of taxpayers’ money at this time of unemployment,” she wrote.

While basic details of the 1921 census were released shortly after its compilation, the digitised records offer the first glimpse at individual returns.

Audrey Collins, historian at the National Archives, said: “We can actually see at first-hand peoples’ quite heartfelt comments. You don’t protest about something if you’re just a little bit irritated; these are real cries from the heart.”

She added: “Undoubtedly, things were very, very grim for an awful lot of people in the 1920s.

“There were an awful lot of people out of work, and that didn’t really get better over the coming decade.

“So I think 1921 is very much a good survey of what the population was settling down to after the rigours of the First World War, but also it was the shape of things to come in the 1920s.”

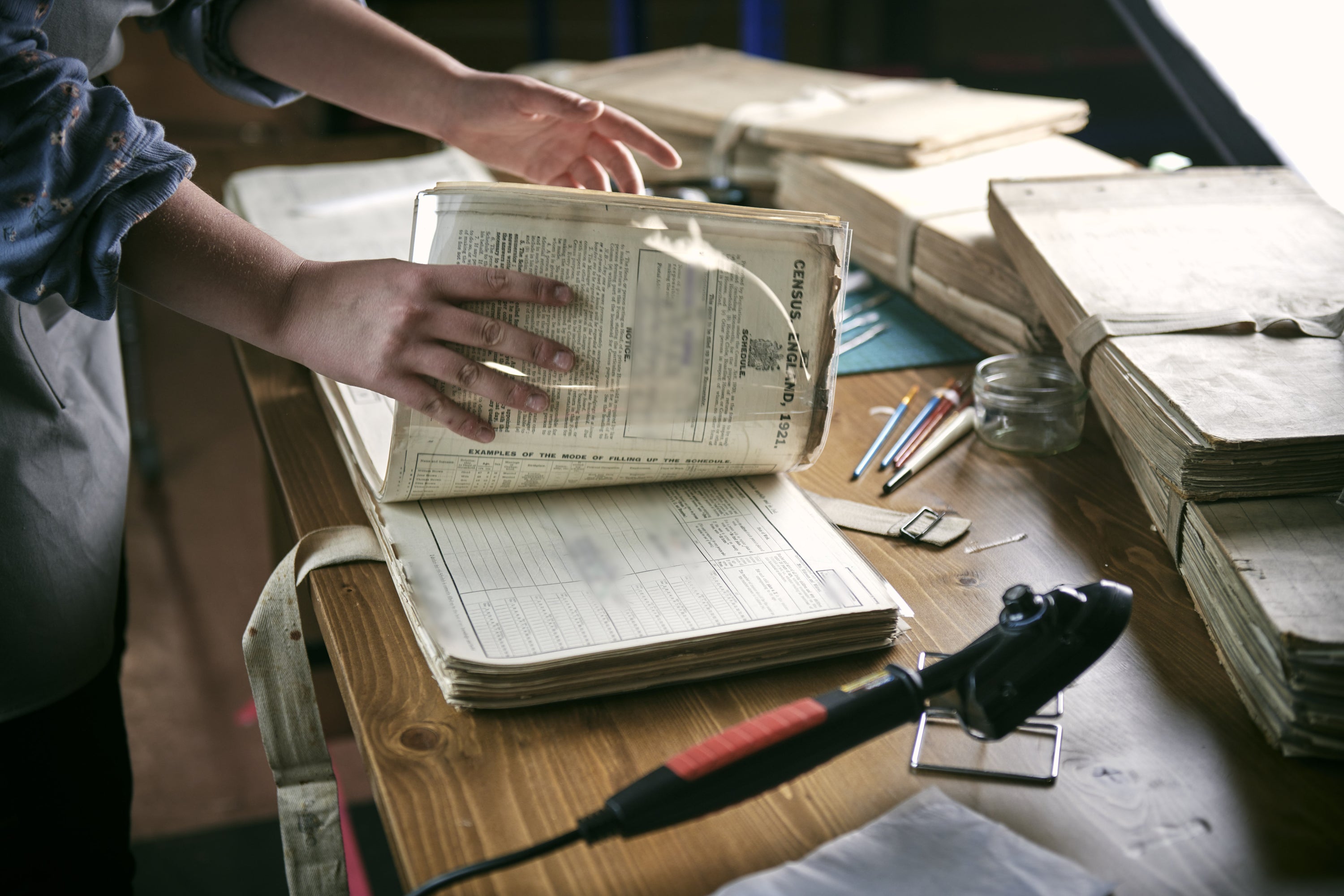

The impact of the First World War is writ large across the millions of census pages, which genealogy website Findmypast and the National Archives have spent three years conserving and digitising.

The census reveals there were 1,096 women for every 1,000 men recorded, the highest discrepancy since the census began in 1801, and by 1951 was still 1,081 per 1,000 men.

This means that in 1921 there were around 1.7 million more women than men in England and Wales, the largest difference ever seen in a census, underlining the deadly significance of the First World War on men.

Indeed the population grew by just 4.9% between 1911 and 1921, to 37.9 million, having previously seen a double-digit increase every decade since records began.

The 1921 census is more detailed than any previously undertaken, having asked people about their place of work, employer and industry for the first time, meaning high street names such as Sainsbury’s, Rolls-Royce and Selfridges appear on its pages.

Unlike previous years, people were also able to declare their marital status as “divorced”, with more than 16,000 people doing so.

However, this figure is expected to be much lower than the actual number due to the stigma surrounding divorce at the time.

Mary McKee, Findmypast census expert, described the careful handling and digitisation of more than 18 million pages of census document as “three years of a labour of love”.

She added: “In terms of the national story, I think it’s going to be impressive what you can find in these records.

“But the other side of it is learning more about our own unique family stories and those individual stories that are found in each individual document.”

The census has been completed every 10 years since 1801, although documents are legally required to remain secret for 100 years.

The 1921 data proved even more significant given the 1931 returns were destroyed in a fire at a storage unit, while the 1941 census was abandoned due to the continuing Second World War.

The most recent census for England and Wales was sent to households in March last year.

The 1921 census is available online at findmypast.co.uk as well as in person at the National Archives in Kew, the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth and the Manchester Central Library.