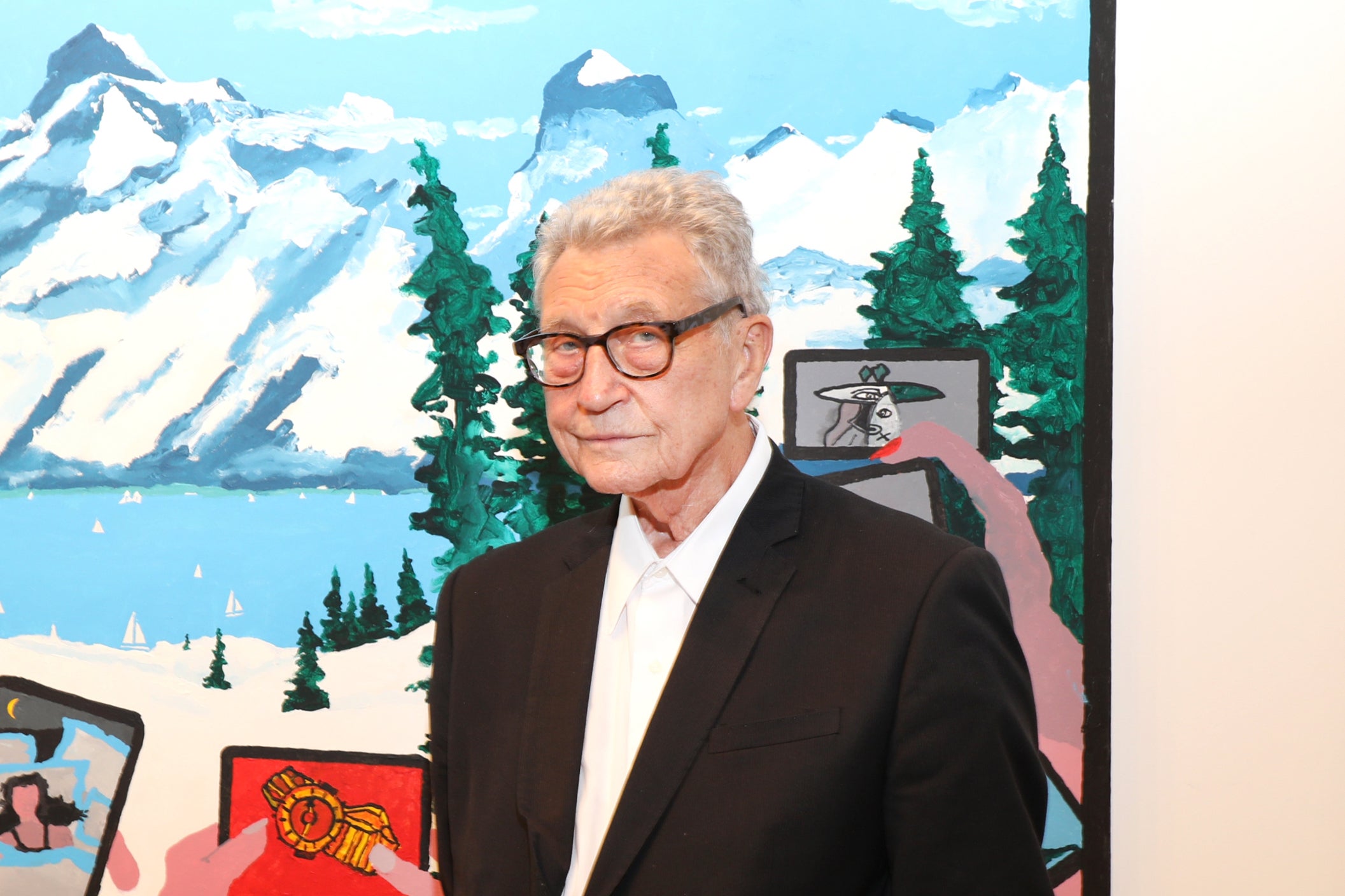

Derek Boshier, Pop Art trailblazer and David Bowie collaborator, dies aged 87

Boshier was the recipient of one of David Bowie’s handwritten notes before his death in 2016

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Derek Boshier, the seminal English artist and leading figure of the British Pop Art scene, has died. He was known for his frequent collaborations with David Bowie, designing two of his album covers.

Boshier’s publicist Daniel Bee confirmed to The Independent that the artist died peacefully in Los Angeles on 5 September at the age of 87.

Mr Bee said: “Derek Boshier undoubtedly helped create and define the Pop Art movement in London and the USA. His observations and commentary around popular culture spanning the last 60 years is clear to be seen in the world’s greatest museums and galleries. He will be greatly missed.”

Born on 6 June 1937 in Portsmouth, Boshier attended the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London from 1959 to 1962, studying alongside luminaries such as David Hockney and RB Kitaj. It was here that he created his iconic painting England’s Glory (1961), which depicts an American flag spreading like an oil spill over a matchbox that bears the painting’s eponymous phrase. In it, Horatio Nelson’s famous quote from the Battle of Trafalgar, “England expects that every man will do his duty,” competes with Kellogg’s Yogi Bear for space, symbolising the unrelenting spread of American consumerism in Britain – a theme that would go on to define his work.

In 1962, Boshier was featured along with Peter Blake, Pauline Boty, and Peter Phillips, in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel –a BBC documentary about Britain’s Pop Art movement. The film captured the emergence of these young artists, exploring their vibrant works and cultural impact.

After his training, Boshier taught at the Central School of Art and Design where one of his pupils was John Mellor, later known as Joe Strummer, of The Clash. This led to Boshier designing The Clash’s second songbook, which included a collection of drawings and paintings released in conjunction with the album Give ’Em Enough Rope.

In the 1970s he shifted from painting to photography, film, video, assemblage, and installations, but returned to painting by the end of the decade. His successful 1979 exhibition, Lives, caught the attention of Bowie, who requested an introduction and kicked off a 37-year friendship.

Boshier designed the cover art for Bowie’s 1979 album Lodger and 1983’s Let’s Dance. He was one of the recipients of a personal handwritten note from the musician shortly before his death in January 2016. In it, Bowie praised Boshier for a recently completed art book and told him his work “cascades down the generations”.

“[Bowie] was marvellous, great to be with, always initiating conversations, he used people in the positive sense, not in the negative sense,” Boshier said in a 2022 interview.

“I found him so interesting and we had a lot of things in common too, British, working class, I was interested in mime.”

Boshier said that the “strongest influence” on his art and life had been his upbringing. “I’ve learnt a lot from that and I’m proud of being working class,” he said.

In his later years, Boshier moved to Los Angeles, California – continuing to tackle serious socio-political themes including gun control and police brutality.

“I’d like to think I contributed something to both the art world and the real world,” he said.

“I always have been and always am conscious of ensuring that every work that I make is not just for the art world but is actually accessible. The point about [my work] is that it’s accessible, you don’t need a text to read … As an artist, you have to make choices about what kind of art you make.

“I’m not an artist that leans towards technology in my work because I always like the feeling of humanity, that’s why [much of it] is hand drawn … the history of my doing this work is apparent.”

He is survived by his second wife and his two children.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments