‘Without a change in the law, there’ll be another Savile’ - Keir Starmer says professionals should be forced to report suspected child abuse

Call for public sector workers who fail to report child abuse suspicions to be prosecuted

Teachers, doctors and social workers who fail to report concerns over suspected cases of child abuse should face criminal charges, one of Britain’s most senior barristers has said.

Keir Starmer, the former Director of Public Prosecutions, has reignited calls for mandatory reporting which would compel all professionals to report suspicions of child abuse or face legal consequences.

In comments to the BBC’s Panorama programme, to be broadcast tonight, Mr Starmer will call for Britain to consider a “very straightforward, simple scheme” that would “change the law and close a gap that’s been there for a very long time”.

The programme will also claim that senior civil servants knew for decades that children’s homes and schools had covered up cases of child abuse. Mr Starmer’s call was supported by the Church of England, with Bishop Paul Butler, chairman of the church’s National Safeguarding Committee, saying: “We have to think of the child first, not ourselves, not the institution. [We must do] what’s best for the child.”

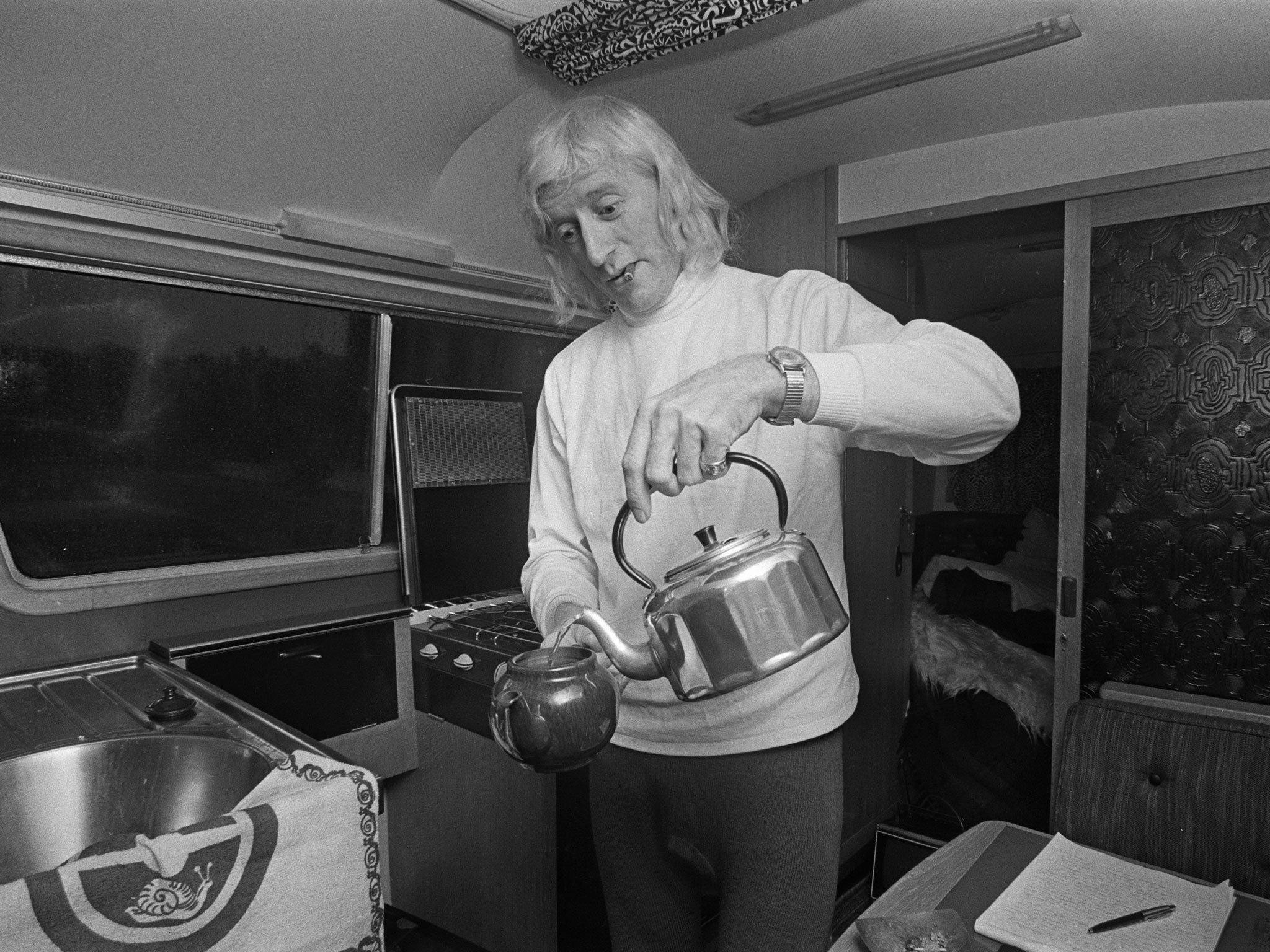

Liz Dux, of Slater & Gordon, the law firm representing 60 of Jimmy Savile’s victims, said she believed that, had there been a mandatory reporting law, details of his abuse could have been passed to the police as early as 1964.

“Countless victims suffered sickening attacks in institutions that were entrusted to keep them safe. Without mandatory reporting legislation, we risk another Savile case,” she said.

Mandatory reporting is already enshrined in law in Canada, Australia, Denmark and several US states including Florida, where a failure to report such cases can result attract a $1m (£600,000) fine. Mr Starmer wants Britain to follow suit with a “direct and clear law everybody understands”.

“The problem is [that] if you haven’t got a central provision requiring people to report, then all you can do is fall back on other provisions that aren’t really designed for that purpose and that usually means they run into difficulties,” he said.

Freedom of Information requests by Panorama reveal that The Royal Alexandra and Albert School in Reigate, Surrey, employed seven child abusers over three decades. Downside, a Catholic boarding school near Bath, had six monks who either sexually assaulted children or viewed images of child abuse between the mid-1960s and early 2000s.

Mr Starmer said such cases were indicative of a collective failure to report. “It’s a very simple proposition. If you’re in a position of authority, and you have cause to believe that a child has been abused, you really ought to do something about it.”

But last night critics warned against creating a “default reporting culture”, arguing that child protection agencies could be overwhelmed and claiming that its success rate was mixed.

David Tucker, the head of policy at the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, said: “Mandatory reporting presents serious problems around confidentiality. Our research shows children will reveal what happens to them in stages, and if they feel that people are obliged [to report their claims], the likelihood is that they will not come forward.

“Research has shown that the child protection system is only dealing with one in nine cases. If you make it mandatory to report concerns then you could end up with a huge number of cases coming into the system. Resources would have to be diverted from existing cases to deal with the assessment.”

Laura Hoyano, a law lecturer at Wadham College, Oxford, said: “Mandatory reporting can disempower professionals from using their judgement and force children into a system that they are simply not ready to engage with. It also sends a message to agencies that you have to take every case – child sex-trafficking or child-bottom-patting – as equal.

“There should, however, be clear mandatory reporting provisions to an independent authority for abuse allegedly committed in an institutional setting.”

The Government has so far resisted calls to introduce mandatory reporting despite growing pressure for a national debate in wake of several high-profile cases. In September, a damning, serious case review revealed that teachers, social workers and police officers in Coventry collectively failed Daniel Pelka, a four-year-old who was tortured, starved and beaten to death by his mother and stepfather. Meanwhile, East Sussex Local Safeguarding Children Board is in the process of compiling a serious case review after it emerged that a school repeatedly failed to prevent a maths teacher from absconding to France with a 15-year-old pupil last year.

Jeremy Forrest, 30, was cautioned about his behaviour by colleagues seven times in seven months with no definitive action taken, and no reports made to police.

Professor Eileen Munro of the London School of Economics, a government adviser on child protection, said: “The debate around mandatory reporting creates a misleading impression that people don’t already have a duty to convey maltreatment if they have any suspicion of it.

“At present, people who make a referral stay involved. They can come to the case conference and be involved in the child protection plan. Countries that have mandatory reporting, like Australia, tend to have a totally different child protection service that has to deal with reports, and nothing else.”

Disclosure by law: Other legal systems

United States: Mandatory reporting was first drawn into laws drafted in 1963. Since then it has become a feature in child abuse laws of 50 states. In Florida failure to report such cases can attract a $1m fine. But increased reporting is not reflected by a fall in child deaths.

Australia: Mandatory reporting exists in varying forms in all states. A comparison of reporting statistics between New South Wales, which had mandatory reporting legislation, and Western Australia, which did not, found that the number of unsubstantiated reports made was much greater in New South Wales – 7,626 compared to 1,196.

Canada: All regions except Yukon Territory have mandatory reporting provisions. Figures from Quebec suggest its introduction resulted in a 100 per cent rise in cases between 1982 and 1989. Although the number of reports kept for investigation decreased from 68 per cent to about 55 per cent, staff in 1989 still had nearly 11,000 additional investigations to conduct compared with 1982.