'Where is the evidence my son was a terrorist?'

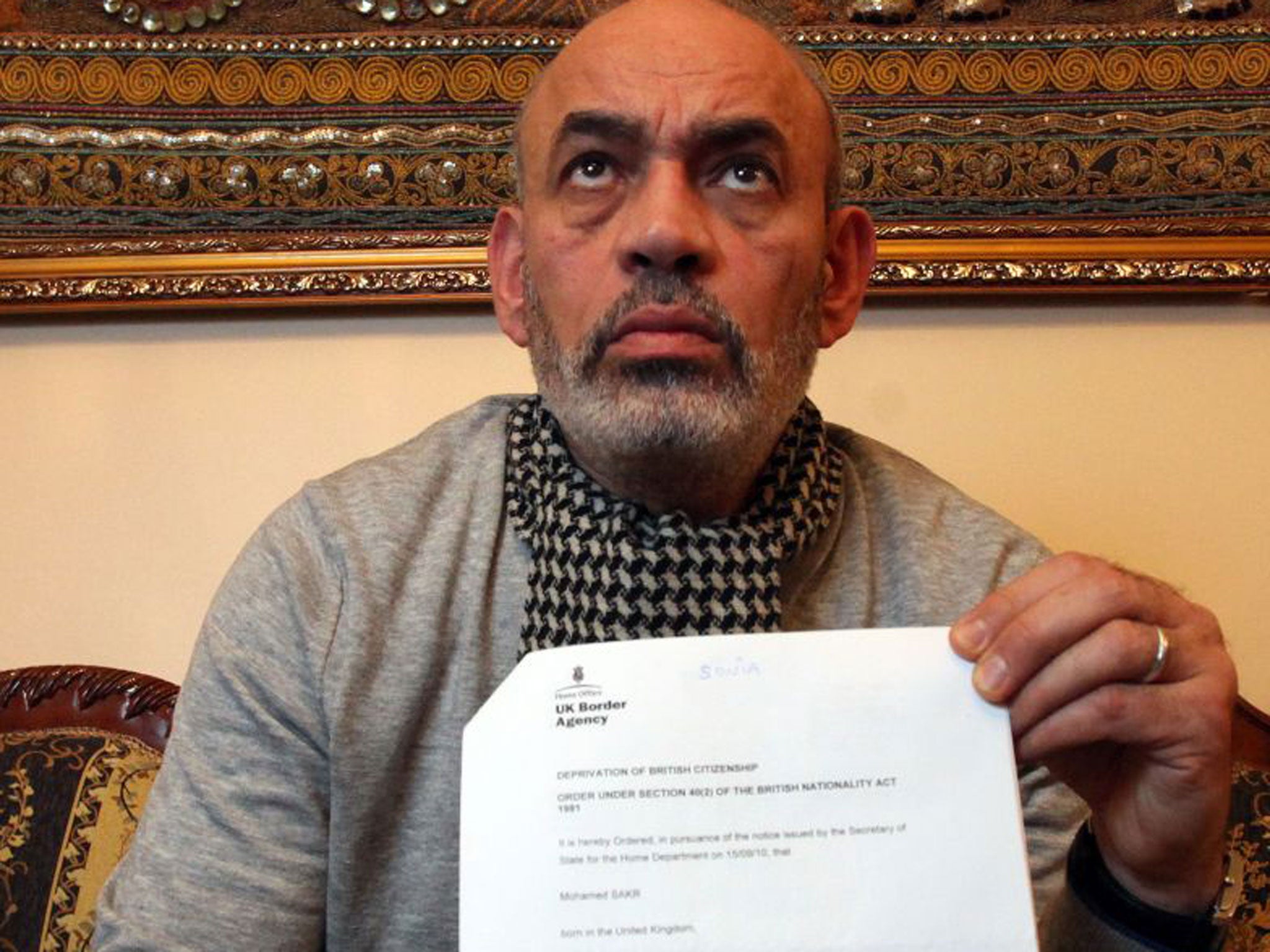

Mohamed Sakr was stripped of his British citizenship for alleged Islamist activity and killed in a drone strike. His parents tell Chris Woods they have yet to be shown any proof of his guilt

The parents of a British-born man killed by a US drone strike after being stripped of his UK citizenship have spoken out for the first time – to say they will never forgive the British Government for his death.

Mohamed Sakr was born and brought up in London before he was targeted and killed in February 2012 in Somalia.

Now his Egyptian-born parents Gamal and Eman Sakr, who have lived in Britain for 35 years, have accused ministers of betraying this country's democratic values.

Speaking to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism from their London home, the couple said they believe their son was left vulnerable to the attack after the Government stripped him of his British citizenship months before he was killed. "This is the hardest time we have ever come across in our family life,' Mr Sakr said in tears. "I'll never stop blaming the British Government for what they did to my son. They broke my family."

The comments follow the revelations by the Bureau and published in The Independent that the Home Secretary Theresa May has ramped up the use of powers allowing her to strip UK citizenship from dual nationals without first proving wrong-doing in the courts. The Coalition has stripped 16 people, including five born in Britain, of their British passports. Two, including Mohamed, were later killed by US drones.

The law states the Government cannot make someone stateless when it removes their citizenship. But Mr and Mrs Sakr say their son Mohamed never had anything other than a British passport, despite in principle having dual nationality.

In 2010 the family received notification that the government intended to remove their son's British citizenship, on the grounds that he was "involved in terrorism-related activity".

"It never crossed my mind that something here in Britain would happen like this, especially as Mohamed had no other passport, no other nationality. He was brought up here: all his life is here," his mother said.

Mohamed's parents were so worried that their other sons might also lose their British citizenship that they renounced the family's dual Egyptian nationalities shortly afterwards. "I did this for the protection of the family, because they grew up here: they were all born here," says Mr Sakr.

"No member of my family ever had an Egyptian passport. For the kids it never crossed my mind that they would have anything other than their British passports. I know they are British, born British, they are British, and carried their British passports."

Mr and Mrs Sakr have thrived in Britain, running a successful business. They moved here from Egypt 35 years ago thinking it was a good place to raise a family.

"It was democratic," Mr Sakr explains. "There was no dictator here, no bad laws like there were back home, so we decided to start a new life."

Mohamed Sakr was born in London in 1985 and grew up as a normal, sporty child. "He was very popular amongst his friends, yet very quiet at the same time, very polite – he was just a normal child," recalls Mrs Sakr.

As he got older his parents worried about him getting into trouble. "He loved going out, he loved to dress up, to wear the best clothes – he liked everything to be top range," recalls Mr Sakr. In his early 20s he calmed down and in 2007 set up an executive car valeting business. His parents thought their son would follow in his father's entrepreneurial footsteps.

But in the summer of the same year Mohamed travelled to Saudi Arabia on what his parents say was a pilgrimage "with a couple of friends and their wives", before heading to Egypt to join his family on holiday. From there, the Sakrs say, Mohamed and his younger brother also visited the family of a girlfriend in Dubai.

His actions were innocent, the family insists. But Mohamed was questioned for "at least three hours" by immigration officials on his return to the UK. The questions focused on the countries he had visited and his reasons for going there.

At the time UK counter-terrorism officials were becoming concerned that a group of radicalised young men was emerging in the capital, influenced by British Islamists who had returned home after fighting in Somalia.

The Sakrs both say that their eldest son was subjected to repeated police "harassment", and was stopped on numerous occasions by plain-clothes officers. Mohamed was spending a lot of time with a friend he had met when he was 12: Bilal al-Berjawi. The two had lived in adjacent flats.

The childhood friends would both lose their British citizenship weeks apart in 2010 – and would die weeks apart too, in covert US air strikes.

Bilal's Lebanese parents had brought him to London as a baby, and like Mohamed, Bilal had drawn the attention of Britain's counter-terrorism agencies. The Sakr family insists they were not aware of any wrong-doing on Mohamed's part, despite his frequent encounters with the police.

In February 2009 Bilal and Sakr visited Kenya for what they told their families was a safari. Both were detained in Nairobi, where they were said to have been interrogated by British intelligence officials. The authorities suspected them of terrorist-related activities. The two men were released and deported back to the UK, but not before the Sakr family home in London was searched by anti-terror police.

Mr Sakr insists he challenged his son about what he had been doing in Africa: "I was asking questions – why has this happened? Mohamed said, 'Daddy, it's finished, it will never happen again. It's all done and dusted.' So I just continued normal life."

In October 2009, the two men again slipped out of the country. Neither told their families they were leaving, or where they were going. Months later Mohamed phoned his parents from Somalia. Both he and Bilal were now living in a country gripped by civil war between radical Islamists and a UN-backed government.

While it has been reported that both men were drawn to terrorist-linked groups, the Sakrs say the pair had innocent connections with the troubled east African nation. Bilal had married a Somali woman in London, and Mohamed at one time had also been engaged to marry a Somali girl.

Most of the allegations against Mohamed and Bilal remain secret. Some information has emerged, however. In November 2009, the pair were named along with a third British man in a Ugandan manhunt, accused of "sneaking into the country" to plot terrorist activities.

Later the men were linked to deadly bombings in that country's capital.

The letter seen by the Bureau informing Mohamed's family that he was losing his citizenship states he was "involved in terrorism-related activity" and for having links with "Islamist extremists", including his friend Bilal al-Berjawi.

The Sakrs remain defensive about these claims. "Do they have any evidence against them that they have been involved in this or that? I haven't seen it. And they haven't come up with it," says Mr Sakr.

In February 2012, news agencies reported that a high-ranking Egyptian al-Qa'ida official had been killed in a US drone strike in Somalia. It would be days before the family realised that those reports actually referred to their son. Mr Sakr says, "They announced Mohamed was Egyptian. They tried to show to the rest of the world he's not British."

Mr Sakr warns that Britain's reported support for US drone strikes – the UK refuses to confirm or deny whether it has supplied intelligence – is a blot on its international reputation.

"If we go and kill everyone based on intelligence information, then we are not living in the world of democracy and justice. We are living in the world of whoever has the power and the weapons to kill," Mr Sakr says.