Vital clue ignored for 50 years

Letter shows Scotland Yard might have nailed Jack the Ripper on fingerprints, had it heeded a humble country surgeon

Some of the most notorious criminals of the 19th century, including Jack the Ripper, might have been caught had the authorities heeded the advice of a village surgeon. A letter written in 1840 and up for auction this week bears his suggestion that fingerprints could be used as a tool for solving murders – some 50 years before they came into use for criminal investigations.

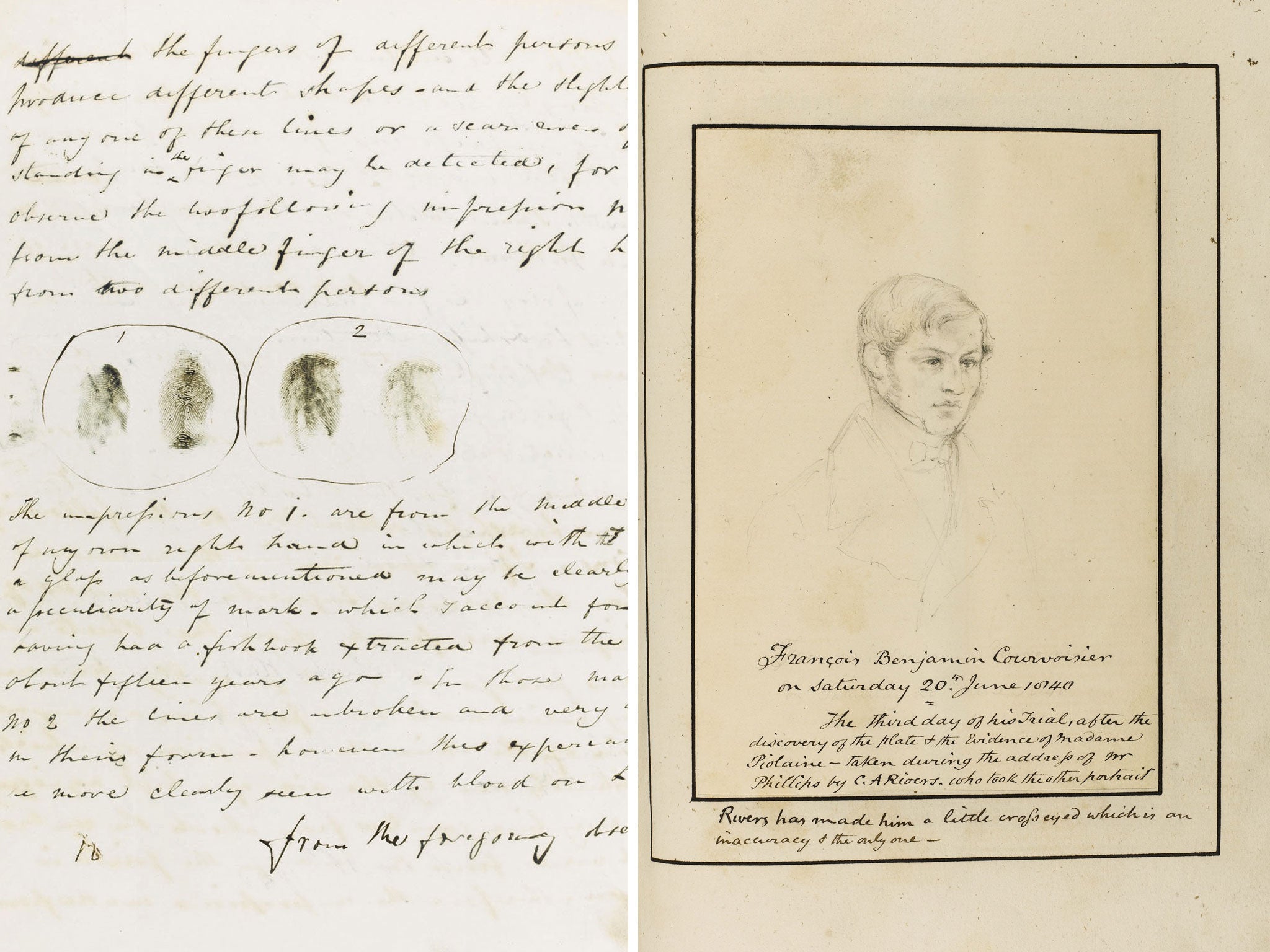

Robert Blake Overton, a surgeon in the Norfolk village of Grimstone, wrote a three-page letter of advice after reading about the murder of Lord William Russell on the night of 5 May, 1840 in his Mayfair townhouse. The discovery of a 73-year-old politician in bed with his throat cut was a huge scandal in its day, sparking a major investigation by the Metropolitan Police, then only 10 years old. Having read lurid newspaper reports of bloody handprints on the sheets, Overton wrote to the victim's nephew, Lord John Russell, the future prime minister: "It is not generally known that every individual has a peculiar arrangement [on] the grain of the skin … I would strongly recommend the propriety of obtaining impressions from the fingers of the suspected individual and a comparison made with the marks on the sheets and pillows." He included examples of inky fingerprints to demonstrate his thesis.

His letter was passed to Scotland Yard. It was found among some 700 original documents relating to the investigation of the murder and subsequent trial. The Law Society is selling the collection through Sotheby's in London on Wednesday. It is expected to fetch around £6,000.

Dr Gabriel Heaton, the auctioneer's manuscript specialist, said: "If this idea had been taken up, the whole criminal history of the Victorian period – of the foggy streets and of Sherlock Holmes and of Jack the Ripper – would have looked very different. They'd have had this incredible tool."

He added: "This obscure village surgeon was suggesting the forensic use of fingerprint evidence for identification purposes a full 50 years before the procedure was adopted. It was only in the 1850s that William Hershel began experimenting with fingerprints as a means to identify villagers in India. Decades passed before the identification process was systematised … and it was not until the 1890s that pioneering use was made of fingerprints in criminal investigations. Even Sherlock Holmes did not use fingerprints until 1903.

"Perhaps even Jack the Ripper might have been caught. Instead, this letter was filed away and Overton himself disappears from the history of forensics."

Ironically, though, fingerprint evidence would not have helped to solve Russell's murder. Scotland Yard did look into Overton's suggestion for the case, recording on the back of the letter that, "there were no such marks". But the police failed to draw the wider implication of the idea.

Although a break-in had been staged, Scotland Yard – which at that time did not have a detective department – soon came to believe it was an inside job. Russell's Swiss valet, François Benjamin Courvoisier, was charged, but evidence proving that he had stolen valuables from Russell only came to light during his trial. Russell had discovered the theft, warning Courvoisier he would be dismissed the next morning. Courvoisier panicked and killed him.

The Sotheby's documents include the note passed to the prosecuting attorney that valuables missing from Russell's home had been found at a hotel whose manager could identify the murderer. Courvoisier confessed, and his execution was attended by thousands, including William Makepeace Thackeray, who conveyed his disgust in his anti-capital punishment essay of July 1840, "Going to See a Man Hanged": "I feel myself ashamed and degraded at the brutal curiosity which took me to that brutal sight."