Why is knife crime increasing in England and Wales?

Shocking statistics show incidents of stabbing have risen by 22 per cent in a year, with children as young as 13 among the victims

Children as young as 13 are being stabbed in a tide of violence sweeping Britain, but the reason for the spike is the subject of fierce argument.

A report by the government cited drug dealing and social media as key drivers, but police have called for more funding to turn around the loss of thousands of officers and voluntary groups are attacking cuts to youth services.

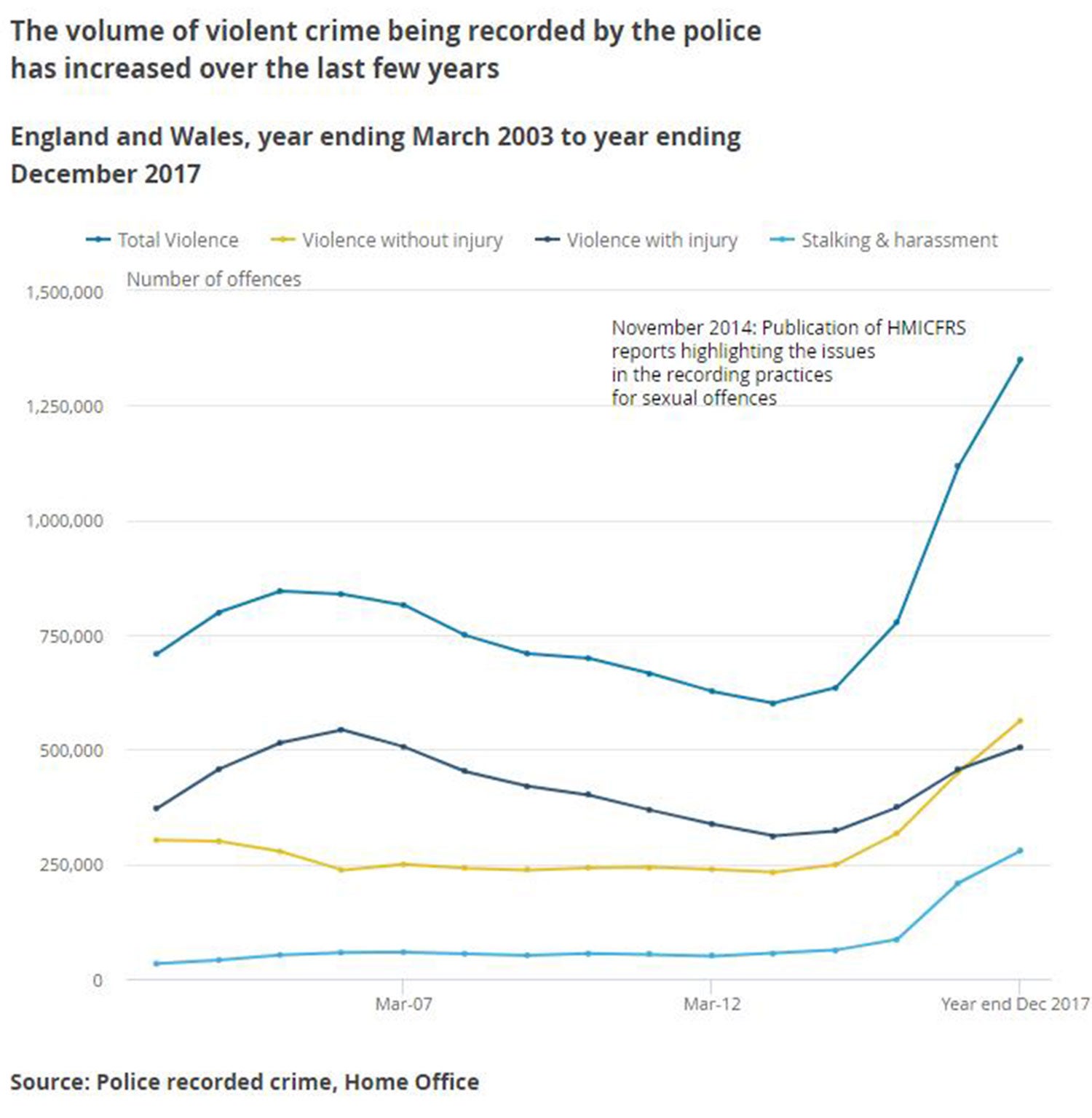

The debate continues amid a bleak background of rising knife crime, which rose by 22 per cent across England and Wales in 2017 – the biggest annual increase ever recorded.

Almost 40,000 offences involving knives or sharp weapons were recorded by police in the year, according figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which said “high harm” criminal offences have been building over the past two years.

The government has repeatedly highlighted improvements in the way police record crime but the ONS said reforms did not fully account for the rise, citing injury figures from the NHS.

There have been more than 60 murders in London alone since the start of this year, amid a spate of stabbings and shootings that saw two teenagers murdered in one night earlier this month.

Junior Smart, of youth charity the St Giles Trust, fears the situation could worsen as the school summer holidays approach.

“If there’s no local youth club providing a safe place to meet, where do they go?” he said. “They’re on the street corners, they’re in the takeaways, they’re congregating and that’s where you get trouble.

“There are petty arguments that might have even started online and violence is how it’s resolved.”

The YMCA said council spending on youth services has fallen by more than £750m since 2010-11 across England and Wales, with the West Midlands and North West hardest hit.

Chief executive Denise Hatton said the vital services are necessary to provide teenagers with positive activities, help them develop, meet new friends and socialise.

“Without drastic action to protect funding and making youth services a statutory service, we are condemning young people to become a lonely, lost generation with nowhere to turn,” she added.

Mr Smart, founder of the SOS Project diverting young people away from gangs, believes a mixture of factors including cuts to youth services, ongoing “postcode wars” between rival groups, drug dealing, social media and falling police officer numbers have worsened the situation.

“When we speak to the young kids they say there are not enough reasons for them not to carry knives,” he told The Independent. “Social media means everything now – these kids have massive following.

“Before there might have been a situation where someone would walk away and back down, but if people are recording this stuff, it can go worldwide.”

The government’s first-ever Serious Violence Strategy, which was released earlier this month, highlighted the impact of social media in the wake of several murders linked to online arguments.

The report said the availability of smartphones has “created an almost unlimited opportunity for rivals to antagonise each other, and for those taunts to be viewed by a much larger audience for a much longer time period”, sparking cycles of tit-for-tat violence.

Social media is also used for drug dealing and recruiting runners by depicting lavish lifestyles perceived as unattainable through legal means.

The growing phenomenon of “county lines” drug gangs, which supply from cities into rural areas, was also cited in the report as a driver of violence because of bloody turf wars between rivals.

Statistics show that the proportion of murders in England and Wales involving known drug dealers and users rose from 50 per cent to 57 per cent between 2014-15 and 2016-17.

Mr Smart said the vast majority of teenagers killed have been “low down on the food chain” and were being exploited by gang leaders known as elders.

“Authorities should follow the money, shut the lines down and get to the people at the top of the tree,” he added. “I was in Manchester last week and in Kent the week before – the same thing is being mirrored everywhere.

“We’ve got to remember that these are children and every life lost is a future extinguished.”

John Sutherland, a retired borough commander in the Metropolitan Police, said the plummeting number of police officers and stretched resources were also having an impact.

“In England and Wales there are 21,000 fewer police officers now than there were in 2010 and that’s the lowest number since comparable record keeping began,” he told The Independent.

“You can’t take that number of police officers off the streets and not expect it to have consequences, it defies common sense.”

The government’s serious violence strategy failed to mention the stark decline, despite a leaked Home Office document suggesting that budget cuts had “likely contributed” to rising violence and “encouraged” offenders.

Mr Sutherland said neighbourhood policing had been “decimated” across the country as a result of cuts, as well as the need to transfer officers from frontline territorial policing into specialist roles and terrorism.

“What that does is reduce the visible presence on the street, damage community relations and confidence building, and the ability to pick up on street-level intelligence,” he added.

Mr Smart agreed, saying that parents in disadvantaged areas who previously felt able to talk to known and trusted neighbourhood officers now only encounter a reactive response.

“A couple of stabbings happen and suddenly there’s visits and weapons sweeps and patrol but it needs to be stable,” he explained.

The recent spike in violence has sparked vows to increase the declining use of stop and search powers, which have been subject to frequent controversy and allegations of racial profiling.

Mr Sutherland said the measure “saves lives” by taking weapons off the streets but warned: “It absolutely is not the long-term answer to what we’re observing with knife crime and youth violence.”

The Home Office has announced a suite of measures, including a Violent Crime Taskforce, increased sentences for carrying knives and acid, a £13m Trusted Relationships Fund to support young people at risk from gang exploitation and a £40m Youth Investment Fund for disadvantaged areas.

A pioneering violence reduction programme that has seen dramatic success in Scotland is also inspiring a series of pilots seeking to give young people opportunities that prevent them from being drawn into gangs and criminality.

The Serious Violence Strategy found that the majority of crime is committed by a small minority of repeat offenders, but a growing number of vulnerable groups are also being exploited.

“Data shows that numbers of children in care, excluded children and homelessness amongst adults have all risen since 2014,” it said.

“These groups possess some of the factors that puts them at higher risk of being exploited for offences such as drug market-related violence.”

Mr Sutherland argued that a core driver of violence has been the failure of successive governments to adopt a long-term approach, leaving the same issues to recur over more than a decade.

“As a society we’re impatient,” the former officer said. “Everybody wants a quick fix and know that stuff is going to be solved next Friday, but when you’re dealing with issues more than a generation in the making that’s delusional.

“I think London needs a 20-year knife crime plan protected from the unpredictability of the electoral timetable and annual funding. This is the real lives of real people and we can’t afford to be mucking around and play partisan games – we need to be doing what’s right and what works.”