The Big Question: Is the 'war on drugs' really making the problem worse?

Why are we asking this now?

Because if confirmation were needed that crackdowns on drug use in the UK were having little effect, it came in a report by the UK Drug Policy Commission (UKDPC), an independent group set up to examine the state of the nation's drug trade.

The report, published yesterday, paints a grim picture, suggesting that the billions of pounds spent on attempts to reduce the availability of drugs on the streets have been in vain. It said there was "remarkably little evidence" that action by customs officials, police and the Serious Organised Crime Agency has had any significant effect in disrupting illegal drug markets. The report argued that the UK should try a radically different approach to tackling the misery brought about by drug-dealing and the crime and social disorder associated with it. Others advocate taking the ultimate step – legalisation.

What is the state of the UK drugs trade?

The report said the UK's illegal drug market was one of the most lucrative in the world, with the trade worth a hefty £5.3bn – a third of the size of the country's tobacco market and 41 per cent of the alcohol market, despite the vast sums spent on attempts to limit supply. Half of the trade centres on two of the most addictive and destructive drugs, crack cocaine and heroin.

The UK's drugs trade is made up of about 3,000 wholesalers and 70,000 street-level dealers. When it comes to the "Mr Bigs" keeping shipments of drugs flowing into the country, there are far fewer. About 300 major importers are bringing in the drugs, said the report.

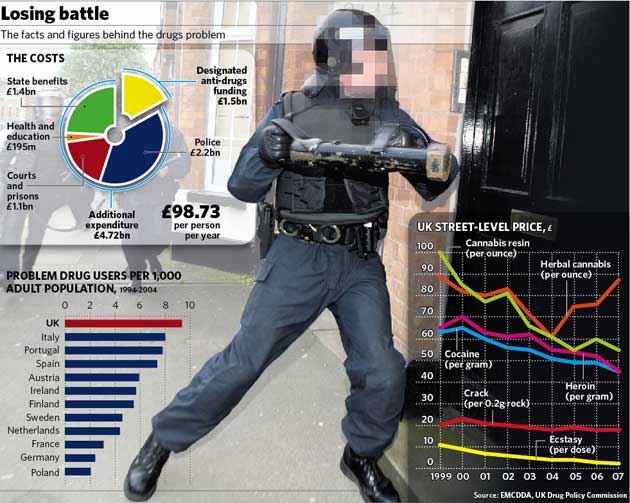

What do we spend trying to cut supplies?

Taxpayers currently shell out £1.5bn on measures designed to tackle the UK's drugs problems. Within that is the £380m that goes towards the reduction of supply, the main target of the report's criticisms. A further £573m goes towards drug abuse treatment. That doesn't even include the massive bill that results from drug-related crime. In 2003-04, that was estimated to have cost the public purse £4bn.

Do seizures have any effect?

The report was unequivocal. It said: "Despite significant drug and asset seizures and drug-related convictions in recent years, drug markets have proven to be extremely resilient. They are highly fluid and adapt effectively to government and law enforcement interventions." It added: "While the availability of controlled drugs is restricted by definition, it appears that additional enforcement efforts have had little adverse effect on the availability of illicit drugs in the UK."

How do we know?

A sure sign that attempts to strangle the supply of drugs have come to little is the fact that prices have continued to fall. Street prices for heroin, cocaine, ecstasy and cannabis have all fallen since the start of the decade. The average price for a gram of heroin in 2000 was £70, but that had fallen to £45 by last year. Cocaine has more than halved in price in some areas – from £65 a gram in 2000 to as little as £30 a gram last year.

Even though the number of seizures more than doubled between 1996 and 2005, that only makes up 12 per cent of heroin and nine per cent of all cocaine. The crux of the problem is that experts believe authorities would need to seize between six and eight times more than that to make a real dent in the drugs business. That doesn't seem realistic, leading some – current and former policemen among them – to call for a change in tactics.

The results of the study came as no surprise to Danny Kushlick, head of policy at the pressure group Transform. He said: "This is nothing new – we've known that prohibition measures haven't worked for 20 years. But the situation is actually worse than the report suggests. It is the measures of prohibition that have caused drugs problems, and pushed the trade into the hands of organised crime and street corner dealers."

Why do current tactics have so little effect?

One of the problems is that the drug trade is extremely adaptable. According to the report, even when a major drug seizure is made or a high-level dealer is convicted, little changes on the streets. Other dealers move in, or the remaining supplies are made less pure so they last through the period of shortage. The dealing and buying, in most cases, carries on regardless.

What needs to change?

For a start, the obsession with big drugs busts. Police having their picture taken in front of table-loads of captured drugs may make a good photo opportunity, but do not do much to help the communities affected by drug dealing, the report said.

David Blakey, a former president of the Association of Chief Police Officers and a commissioner for UKDPC, said the police were still being judged on old measures, such as seizure rates. "This is a pity as it is very difficult to show that increasing drug seizures actually leads to less drug-related harm," he said. "Of course, drug dealers must be brought to justice, but we should recognise and encourage the wider role that the police and other law enforcement officials can play in reducing the impact of drug markets on our communities."

Instead, more emphasis should be placed on hitting drug markets that cause the most "collateral damage" to surrounding communities – such as dealing associated with prostitution, human trafficking and gang violence.

Anything else?

Instead of going after the never-ending supply of bad guys, it suggests tackling issues from the point of view of the communities hardest hit by the drugs trade. Above all, it claims that forming partnerships between police, local communities and other related workers is vital in ridding an area of drug problems. It also advocates prevention – tackling problem-spots before they get out of hand.

Should we just legalise drugs and have done with it?

According to its advocates, including the Chief Constable of North Wales Police, Richard Brunstrom, and Transform, legalisation would turn drug-taking from a crime issue into a health issue. Drugs could be vetted for their quality, while the trade would be taken from the grasps of criminal gangs and drug lords.

Legalisation seems to be making a lot of sense to many. Even some politicians admit to being sympathetic to the idea in private. But there is one glaring problem with the policy – the Amsterdam issue. When hedonists around the world got wind of the city's liberal drugs laws and hash cafes, they all started making the pilgrimage. Would many people really tolerate the influx of a new type of hedonist holiday-maker? Probably not. Until the whole world agrees to end prohibition at the same time, it will probably remain impossible.

So is the approach counter-productive?

Yes...

* Preventing supply has been very unsuccessful – the drugs trade is worth £5.3bn

* A sharp fall in street prices since 2000 suggests more than ever is getting through

* Even after big seizures and arrests, other dealers simply move in to fill the gap

No...

* Tackling supply is only one strand of the strategy – more is spent on treatment

* Police must make high-profile seizures for as long as they are judged on them

* Trying other approaches to the problem should not mean drug dealers escape justice